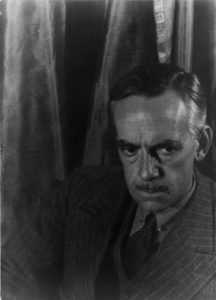

One of the most daunting plays for any actor to tackle is Eugene O’Neill’s Long Day’s Journey Into Night. Amongst those who have tackled role of patriarch James Tyrone are Laurence Olivier, Jack Lemmon, Jason Robards, Gabriel Bryne and Brian Dennehy. You can now add Oscar and Tony winner Jeremy Irons to that list. He stars in the Bristol Old Vic production of O’Neill’s semi-autobiographical family drama that opens this weekend at the Wallis Annenberg Center for the Performing Arts. He’s joined onstage by Lesley Manville (Oscar-nominee for last year’s The Phantom Thread), Matthew Beard, Rory Keenan and Jessica Regan. Richard Eyre is the director.

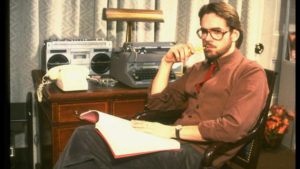

Irons has only appeared on stage once before in Los Angeles. He played King Arthur in a one-night only production of the musical Camelot in 2005. He has done far more theatre in the United Kingdom. Irons won the Tony Award for his performance in The Real Thing by Tom Stoppard. He’s known for countless film roles in such films as The French Lieutenant’s Woman, Dead Ringers, Reversal of Fortune (his Oscar-winning performance), and most recently for playing Alfred in Batman v. Superman and Justice League.

I recently spoke by phone with Irons while he was in New York with the play at the Brooklyn Academy of Music. We discussed the challenges this role presents, playing a role so many others have done before and why he finds this four-act play about a dysfunctional family so alluring.

When Brian Dennehy was interviewed by the New York Times in 2003 about the production of Long Day’s Journey in which he appeared, he said “There are truths told in this play, as in any great classic, that have to be heard over and over and over again.” What are the truths, from your point of view, that need to be heard?

There are so many, but, what you fear and what you learn when you are acting a role is often different than what the audience gets. There are great truths in this because he wrote it not to be performed. He wrote it as catharsis for himself. I think that’s why it’s so great and so flawed a play. He was dredging up the bottom of his soul and putting it on the page.

There are so many truths within it about how you affect your children, how you view life through the doors of your understanding. I think it is really a hell of a play. And it’s full of the love/hate that’s in most families. Like all great theatre it makes us realize we aren’t alone; that other people go through similar things that we do. When you see it with an audience, there’s something uplifting about it, even though it is a fairly grim subject.

In the play Mary has been pretty damaged by James. How do you tackle his demons within a character who doesn’t possess the self-awareness to realize what he’s actually done to her or the family?

I think on the last line it probably just sinks in when she says, “The in the spring something happened to me. Yes, I remember. I fell in love with James Tyrone and was so happy for a time.” I think O’Neill writes that he shifts in his chair and at that point he realizes that it’s the life he made her lead of the traveling player. Some women could have coped with that. This one couldn’t. She wasn’t strong enough to do what he asked. She should have stayed with her children when they were very young. But we all make mistakes in life. We are what we are and I think one of the great things about this play is O’Neill doesn’t seem to judge. He says this is humankind. This is my family. Everybody does the best they can in life, generally, all of us. The O’Neill’s or the Tyrone’s are no different.

Long Day’s Journey has been analyzed continuously since it was first performed. Does that analysis help you in building your character?

Basically I go from the text. That’s what makes people go back to see Shakespeare and O’Neill is no different. They want to see what particular actors can make of it. I bring different things than Brian Dennehy, Jack Lemmon, Laurence Olivier and all the people I’ve seen. The play can accommodate that. Some actors are able to play up certain aspects better than others. It’s always different and the play is always different and re-watchable as a result.

If you have a chance you want to see what other people’s choices were and compare them with yours. Allow them to be devil’s advocate and see what the options are. Finally it’s a question of looking over your shoulder and finally you go your own way and look inside yourself. I use what I can with my instrument. And it will be inevitably different and I hope it doesn’t suffer too much by comparison.

The pace of this production is considerably faster than most. Is there something new that you learned about the play by picking up the pace?

I think we play the first couple of scenes at a fair old lick. We’ve had to slow it down a little bit for New York because of the nature of the theatre, but I hope we can pick it up again in Los Angeles because we have a different shaped auditorium. I love what we do. The audience really has to work to listen and to watch. It gives us an arc because this play slows down and gets deeper and heavier as it goes on. I was very pleased when Richard encouraged us to do that. It stops individual lines from becoming sacrosanct and having an importance they don’t deserve. And I don’t think you should make the audience sit still for longer than they deserve. Audiences have to work for a play to work. And in any conversation, if both sides aren’t interested there isn’t a conversation. I do think for some people when they are in the right place the production can be devastating.

In a 1922 interview, O’Neill said “The point is that life in itself is nothing. It is the dream that keeps us fighting, willing-living! Achievement, in the narrow sense of possession, is a stale finale.” Would you say that point of view applies to the Tyrone family and by extension the O’Neill family?

I think that’s at the core of Tyrone’s confession to his son that he has worked to have things, to have property, to have a summer home, to have security. I don’t know about all actors, but certainly I was always aware that the next job, you don’t know where it’s coming from and what it will have to pay. You know an actor’s career goes through ups and downs. So it’s very comfortable to have a financial cushion if you are raising a family. What we need is to be challenged. That’s why I did the play. I’m sort of comfortable. I’ve brought up a family and we have a cushion.

Doing a play like Long Day’s Journey, where you are putting yourself on the line, you are being compared to others who have done it, you are doing a long, difficult play to learn and difficult play to get right. Does one need to at the age of 69? I think you do. I’ve always felt that risk was extra life. It feeds you. Putting in front of you the possibility of failure and going ahead and seeing if you can get over it is very good. And for me it’s been tremendously energizing doing this play because it is real work. There’s no messing around with it. It’s so important to keep going back to theatre, to find these great parts, and give yourself the opportunity of falling flat on your face. That’s what keeps me going.

Go here to read part two of our interview with Jeremy Irons where he discusses his highly-acclaimed recordings of the poetry of TS Eliot, the meaning of awards and if Irons can ever fully know a character he plays.

A great atrocity presented in this play is the overwhelming cocaine addiction so many women homemakers succumbed to when it was added to medicine sold for various treatments. It was because of this addiction the FDA was eventually formed in 1921 to start controlling narcotics state-wide.