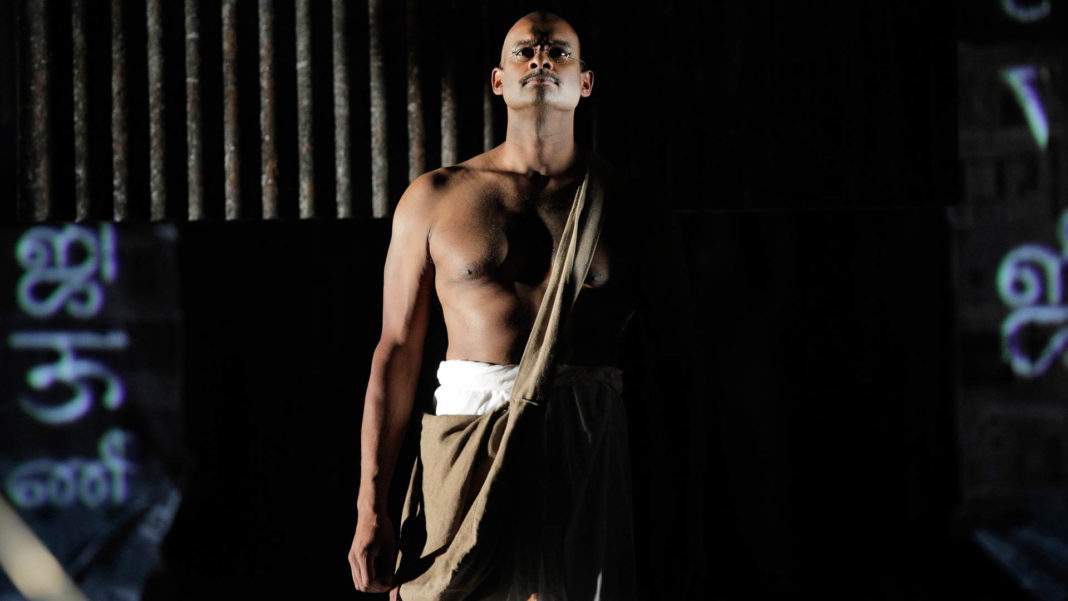

There is so much to admire and love in LA Opera’s production of the Philip Glass opera Satyagraha that it would be easy to do multiple stories talking about this stunning and ultimately quite moving production (which runs through November 11.) But for an opera about Gandhi, the weight of the production falls on the tenor singing that role. Thankfully Sean Panikkar has strong shoulders to carry that weight.

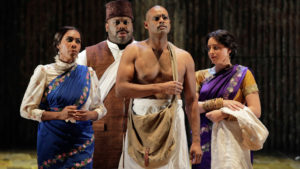

Not only does he carry the weight of playing such a revered man, Panikkar is the first person of South Asian descent (he was born in Pennsylvania to Sri Lankan immigrant parents) to play Gandhi in any of director Phelim McDermott’s productions of the opera. He might also be the first South Asian singer to play the part ever. As he told me when we spoke on the phone before Satyagraha opened at the Dorothy Chandler Pavilion, “There aren’t many roles written for a South Asian. There’s the role of Gandhi here and there’s The Pearl Fishers and I’ve done that a lot. It takes place in Sri Lanka. I’ve done performances with people spray-tanned orange. There’s not that many South Asian singers.”

By his own admission, Panikkar was not initially a fan of Philip Glass’s operas. “When I heard Einstein on the Beach, I was a double major in engineering and vocal performance, I didn’t get it at the time,” he reveals. “It bothered me to listen to this.” But it was a phone call asking him to perform the final aria from Satyagraha for a 2010 National Endowment for the Arts Honors where Glass was a recipient that changed things. “I said ‘I’m not going to be able to sing Philip Glass.’ I listened to the aria and still to this day I get goosebumps. It’s one of the most beautiful things. I called my manager after that and said, ‘At some point I want to sing Satyagraha.'”

The text of Satyagraha (which means “Truth force”) is by Constance DeJong and adapted from the Baghavad Gita, allowing Panikkar another way into the opera. “My father’s father could write Sanskrit. My mother is Hindu. I grew up in a household with multiple religions. But I was familiar with the chanting of Sanskrit. I took the Sanskrit very seriously and did my own transliteration of it.”

Among challenges of performing this work is singing the music Glass has written which puts unique demands on Pannikar. “It’s complicated and difficult in ways that you don’t normally encounter in opera. Gandhi is not very high. It’s in the lower and middle part of your voice, but tenors aren’t used to sitting there all night. The amount of focus to perform this piece is unlike anything I’ve ever done. Not only are you counting and having to remember which number sequence you are on, you are dealing with repeats that have very minor rhythmic variations. The other thing, too, that’s strange for singers and I don’t struggle with this, but in an opera like this you really have to check your ego at the door. There is kind of like no glory in it, if you know what I mean. It takes a different kind of personality to sing some of this music.”

Gandhi himself was known for his stillness. I asked Panikkar about how important that is in singing this role. “Oh gosh…stillness is a huge part of this,” he says while letting out a little laugh. “That’s one of the things that was tricky at first. Singers are used to moving and engaging their bodies in ways that are advantageous for vocal support. This has a slowness that feels very restrictive, but after a few days of rehearsals you start feeling the freedom in that. You start realizing that there is that power in just being there and not doing anything physically. You don’t have to wave your hands and run across the stage. You can convey Gandhi in the movement of the stillness.”

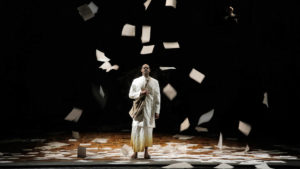

Being part of Satyagraha has lead to some eye-opening conversations with the company. When discussing a key moment in the opera when Gandhi is pelted by the crowd with balled up paper, Panikkar shares the ensemble’s unique perspective. “Some of the people in the production, and I believe it’s been eleven years since Phelim put this together, they said this is the first time it actually felt terrible because they had never been attacking someone who wasn’t white. I know I feel it very personally and they feel it very personally. I think visually it makes a difference when you are seeing something closer to reality.”

Before we concluded our conversation, I asked Panikkar how prevalent racism is in opera. “It’s like how much racism is there in real life,” he said. “It’s there and it’s not spoken about and it’s not overt. There are lots of barriers to hide behind in opera. Because music is so subjective, whether you like a voice or not is subjective. Because of that there never has to be an explanation for why someone did or didn’t get a job. It’s just in the opinion of whoever is casting the part. I’m sure there are times I got roles because of the way I look and there are times when I didn’t because of that. There are times I get it just because of the way I sing. I can’t dwell on that because there’s nothing I can do. All I can dwell on is what I can make better in my technique or style. I can’t wake up tomorrow and be a white man. Everything I’ve experienced helps inform what I do on stage for whatever character I’m playing.”

Main photo by Cory Weaver/LA Opera.