Larry Kramer’s play The Normal Heart is finally a movie—and it only took 29 years. Directed by Glee and American Horror Story creator Ryan Murphy (he also did Eat, Pray, Love) the film began airing on HBO this past weekend. But before it was a TV movie, it was a landmark play penned by writer and AIDS activist Larry Kramer. It debuted in the spring of 1985 at New York’s Public Theatre. In December of that same year a production opened at the Las Palmas Theatre in Hollywood. The cast included Kathy Bates, Bruce Davison, and, in the lead role of Ned Weeks, a young Richard Dreyfuss, who at that point was probably best known for starring in Close Encounters of the Third Kind.

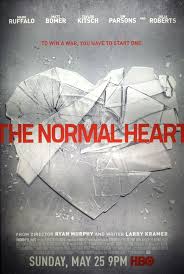

Set in the early 1980s The Normal Heart depicts the first years of the AIDS crisis. Ned (played by Mark Ruffalo in the film) and several colleagues form the Gay Men’s Health Crisis in an effort to help men who are dying from the “gay cancer.†Weeks’s activism inflames government officials and alienates his friends, but desperate times demand desperate solutions. The Normal Heart essentially depicts Kramer’s experiences during that era.

“Every night Bruce and I kissed,†Dreyfuss recalls, “some guy in the audience would slam his program down and say ‘Goddamnit, I’m getting out of here.’ That’s when we knew we were doing it right. It’s a great role and it was timely. It’s like the theatrical parallel of [The Apprenticeship of] Duddy Kravitz. The whole play is a scream of empathy and love. It doesn’t matter that he’s an irritant; look at what he’s fighting.â€

The Normal Heart finally reached Broadway in 2011. At certain performances Kramer could be found outside the John Golden Theatre handing out flyers to remind the audience that HIV/AIDS hasn’t gone away and that there is more that needs to be done. Clearly the fire still burns. “Larry himself is more willing to go toe-to-toe with people because he’s been going toe-to-toe, like the scene with the mayor,†says Dreyfuss. “Anyone with a brain knows this is a man who is grieving over the loss of his own. He may have a posture, he can misinterpret a phrase and take it as something to ignite, but for the most part he’s a sweet gentleman. As a matter of fact, I’m kind of grieving that we haven’t talked in a bunch of years.â€

“The most important moment was two years after The Normal Heart came out,†Dreyfuss says. “I spoke to [Larry] and he said, ‘I went to the island and they acted as if the play had never been written. They are behaving like they did before.’ And his heart broke. He realized, and I’m making this up, that his opponent was no longer the straight world, it was the gay world. It was like these kids had never experienced or cared about what he had been writing about and they were behaving as they had in 1969. It killed him.â€

With actors today still being encouraged not to “play gay,†did Dreyfuss or his agents have any concern about appearing in this play? “No one ever said that or ever would who knew me. Not even in the slightest.†It was the challenge of the role that inspired him. “The challenges were the speeches. There were problems in the staging of the actors at certain moments. There’s that blasting confession when Bruce dies that was never really fulfilled as it should have been. But it’s a pretty exciting thing to provoke an audience into demanding that they listen and watch—and they did.â€

Does Dreyfuss believe we’ve made progress since 1985? “There were markers along the way like when Magic [Johnson] got sick and talked about it and when Doris Day came out for Rock Hudson. Slowly we began to lose our hostility and fear. However, it would also help to remind different sectors of society—doctors, pharmaceutical companies, gay people, right wingers, Vice Presidents of the United States whose children are gay—there’s more connection than disconnection.â€

Dreyfuss, who has always spoken his mind, does not have any plans to return to the stage at the moment. “In a certain way I stepped away from acting. Now when I act, I do it to make a living and feed my family. It’s not the love affair it had been for 50 years; it’s a friendship. We have this strange inability to ask the most talented industry in the world to get involved in theater in their own town. And we don’t know how to offer them anything to make this work. I say offer them something they don’t have: complete artistic freedom. And that way you get Steven Spielberg, Warren Beatty, and Francis Ford Coppola to do theater.â€