“I conducted every piece of music for him in his lifetime,” conductor John Mauceri says of his time with composer/conductor Leonard Bernstein. Of course he is referring to every piece of music Bernstein wrote. “The composer was articulate and trusted my work and felt completely free to give me advice on what I needed to perform his music.”

That experience and insight will come in handy on Friday night when Mauceri takes to the podium with the New West Symphony at the Valley Performing Arts Center in a program entitled Bernstein on Stage. The concert will focus on Bernstein’s music for such musicals as West Side Story, Wonderful Town, Candide, and On the Town. Mauceri, who was the Director of the Hollywood Bowl Orchestra from 1991-2006, spent 18 years working with the man his friends called “Lenny.”

“When you were with Leonard Bernstein,” Mauceri recalls, “that’s just where you wanted to be because he was a life force. He was fun and interesting and funny. He was one of the funniest people I ever knew. He would spend time as if you were equals. He made that clear when we first met in 1971-1972. He would ask my opinions as if we were equals. That unlocks your sense of security, that you are worthy of having those conversations.”

Much like his lyricist for West Side Story, Stephen Sondheim, Bernstein thrived on collaboration. “One of the reasons why Lenny generally enjoyed and flourished in musical theatre was because it was collaborative,” Mauceri says. “Most people don’t think about it but being a composer is a very solitary job. Lenny had a harder time being alone with himself and being alone from the very public world of conducting. When he wrote with Betty [Comden] & Adolph [Green] (Wonderful Town, On the Town) or with Jerry [Robbins], Arthur [Laurents] and Steve [Sondheim], this was a happy time.”

One show of Bernstein’s that failed spectacularly was the musical 1600 Pennyslvania Avenue. The show only ran for seven performances. Mauceri remembers a conversation just before Bernstein died about wanting to rework it. “He asked me to be the original music director and I was unable to do it. It was one of the rare times I had to say ‘no’ to him. The Thursday night before he passed away he talked about fixing 1600. I have a very personal commitment to it. It does contain some of the best music he ever wrote and some of the best and most interesting lyrics by Alan Jay Lerner.” [Music from this show will be performed at Friday’s concert.]

For all the positivity Mauceri referenced about his mentor, I had to ask about Hershey Felder’s depiction of Bernstein in Maestro as bitterly disappointed that he’d primarily be remembered for the melody to “Somewhere” in West Side Story.

“It’s just part of historical fiction,” Mauceri says. “I didn’t see the show. I never heard Leonard Bernstein say anything like that. I don’t think he was disappointed. He made choices that eliminated other aspects of his time. When he decided to become the New York Philharmonic Music Director just as West Side Story was opening, he made a decision that he would otherwise give to time writing his own music. He became committed to championing other people’s music. For a conductor it is our fundamental job. Part of our service as conductors is to support and perform music of other composers. His influence was a great, if not greater, because of his years with the NY Phil. I don’t think he was bitter about any of them.”

Bernstein once said “The key to the mystery of a great artist is that for reasons unknown, he will give away his energies and his life just to make sure that one note follows another…and leaves us with the feeling that something is right in the world.” What feeling does Bernstein’s music leave Mauceri with after all these years of up close and intimate contact and familiarity with it?

“The underlying goal that Leonard Bernstein had was uplift. It was very much inspired by his love for Beethoven whom he considered the greatest composer of all time. Every work ultimately is about that. Whether it is joyful and simple or complex, its goal is to unite the audience to make a better place. In any piece he may be arguing with God or politics, but all those arguments are lovers’ quarrels. They are not negativity for negativity’s sake. They are about ultimately uplifting an audience.”

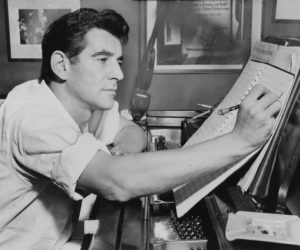

Photo Courtesy of Columbia Artists Management Inc. (CAMI)

UPDATE: Hershey Felder responded to my question about his depiction of Leonard Bernstein in “Maestro.” Here is the response he e-mailed:

My office has the habit of sending me articles that pop up on google alert that could be interesting to me, and I just received your article. Most wonderfully, I had the opportunity to see and then read many more of your wonderful articles, that are beautifully and thoughtfully written. Of course I write because of your mention of MAESTRO in which I suggest, not exactly that Bernstein was disappointed by people only remembering him for “Somewhere,” but really suggesting that he was extremely bitter that he believed he would only be remembered for West Side Story, with “Somewhere” as an example. As Mr. Mauceri says, there is great importance in recognizing the “uplift” of Maestro Bernstein because of what you write about – what he stood for, and what he instigated and made possible for American musicians, music, and all musicians in general. I must say, I don’t know if the stories I was told about the Maestro’s bitterness at the end were fictional or not, despite having come from sources who claimed to have witnessed such outbursts. I was not present myself, and cannot confirm myself. But I can safely say this idea is not “historical fiction,” but in fact the way a good number of people close to the Maestro report how it was. It may not have been Mr. Mauceri’s experience, but that does not make it a “cultural historical fiction.” – Hershey Felder – November 15, 2017