Last week we talked with Matthew Aucoin about his role as conductor for the LA Opera production of Rigoletto. Today we are talking again with him about the upcoming concert performances of his opera Crossing. This is Matthew Aucoin: Opera Composer. These performances will be held at the Wallis Annenberg Center for the Performing Arts on May 25th and 26th. Aucoin will be conducting both performances.

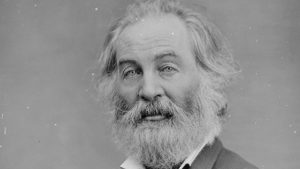

Crossing depicts a time in the life of poet Walt Whitman when he put his work aside and volunteered as a nurse helping with soldiers during the American Civil War. Baritone Rod Gilfry plays Whitman, a role he originated in the world premiere of this work in 2015.

I spoke with Aucoin by phone while he was working on an operatic adaptation of Sarah Ruhl’s 2003 play, Eurydice which will find its world premiere in a future LA Opera season.

What can we learn from this part of Walt Whitman’s life that you think is unique to what we know about other parts of his life and/or directly what we learn from his poetry?

It’s a crazy thing to do for a middle-aged guy who was living a pretty comfortable life in New York to drop everything and work for no money for three years in the most demanding and gruesome work imaginable. Whitman describes regularly seeing piles of amputated limbs. It wasn’t a pleasant place to be. What lead him to do this? What kept him there? He didn’t plan on staying. He was visiting his brother and then his brother got better and release and Whitman stayed.

I doubted the purity of his motives. After all, here is a middle-aged gay man spending his days with all these 18-20 year olds. In the diaries he does record being on fairly intimate terms with them. I’m not suggesting he was some sort of predator. I think there was a personal need for him to be there. There are also signs of a mid-life crisis. He was a guy who kept reinventing himself. Being a nurse was just another invention of this chameleon of a human being.

Where do you take this story in Crossing?

What I wanted to do was paint this psychological portrait of Walt Whitman in this sort of purgatory. Nobody knows how long the war will go on. The patients don’t know if they will get out alive. Whitman doesn’t know why he’s stuck there. Of course we see the end of the war in the epic and what that does to Whitman. He has to confront that he’s in refuge there. It’s a fraught moment for both Whitman and the country.

When you were writing the libretto for Crossing you had to contend with a subject matter whose own poetry has been embraced and celebrated for more than a century. What influence did his style have on you and how daunting was waxing poetic about a poet?

Of course it was daunting and I started the process by setting a few Whitman poems to music just to be sure that I could. I actually think the vast majority of Whitman is essentially impossible to set to music. The lines are too long to sing in one breath a lot of the time. But I found a few poems of his such as The Sleepers and A Clear Midnight which did suggest music to me. That was comforting.

For the rest of the opera I didn’t actually quote much Whitman because the point here is not to show him in his poet/prophet mode so much as to show him as a complicated, tormented but sympathetic human being. So of course he speaks differently in conversation than he does in the poems.

In Leaves of Grass Whitman depicts his conflict and emotions about a gay affair and its aftermath. Was any of that work at all influential in the writing of Crossing?

No. But there are references to his sexuality through the poems. One that fascinates is in The Sleepers. The whole poem is about sleep as democratizing forces. Humanity is all the same when it sleeps. Whitman imagines himself as the only person who can’t sleep. He imagines walking and being this all-seeing eye that is doomed to be conscious. Then he has this dream where he switches gender – he imagines himself as a woman. It’s this bizarre confession. It blows my mind that this was published in the 1850s. He does fall in love in the opera with one solider who has his own secret. The kid snaps and calls him a “twisted old faggot,” but not in modern terms. The way Whitman responds is, I’m just trying to be everyone’s brother. I find that touching because that’s a s close as he could get to expressing sexual desires.

What makes Rod Gilfry the right person to have created this role?

Rod is one of the most lovable artists you will ever meet. He’s got this beautiful lyric baritone voice which as he has matured, it has a couple rough edges in the good sense. There’s a lot of experience in that voice. But he’s still, at heart, a sunny California dude. I met him when I was assistant conductor at the Metropolitan Opera working on Thomas Ades’ Tempest. Rod sung the role of Prospero a number of times. Through all the changes I’ve made to Crossing, I’ve kept tweaking it so it’s a tailor-made suit for him by now.

In your lecture about Whitman at Paine Hall, you talk about the “extraordinary decision to spend years of his life volunteering in Civil War hospitals.” What, in your own life, is the extraordinary decision you’ve had to make, whether personally or creatively?

I don’t think I’ve jumped off an equivalent ledge of security, except for the one living as a composer. That took some guts because you have to say no to a lot of the commercial machinery that makes our world tick. You have to be okay with standing outside of that. I used to play in a rock band and I loved it, but I couldn’t stand the creative limitations. In the classical music business we are up against economic realities every day. Part of the reason we are struggling is we are making decisions for artistic reasons and I think that’s something to celebrate, not just to bemoan the audiences are smaller. Yeah, it takes some effort to engage with this music.