Though it isn’t that story, it is a tale as old as time. A young man, who grows up in the church, is thrown out of that church he loves for being gay. It’s a story that happens all-too-frequently – as it did for Griffin Matthews. Except that when it happened to him, he chose to go to Uganda to spend time as a volunteer in an impoverished community. What makes his experience unique is that it serves as the foundation for “a documentary musical” that Matthews wrote with Matt Gould. That musical is Witness Uganda and it officially opens at the Lovelace Studio Theatre at the Wallis Annenberg Center for the Performing Arts on Friday. The show will continue there through February 23rd.

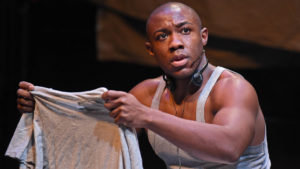

Matthews and Gould have made changes to their show since it was presented in New York under the title Invisible Thread. This production, which stars Ledisi, Jamar Williams, Amber Iman and Emma Hunton, is directed by Matthews. Gould serves as Music Director.

I recently spoke with both men, who in addition to being collaborators are also married, about the circumstances that forced Matthews to find a new path elsewhere, the changes made to the show and also his decision to go to such a horribly anti-gay country in the first place.

When you are creating a show out of your own experiences, how do you balance what’s right for a show versus what is historically accurate to those experiences?

Matthews: Something that for me I try to live by when we are making art is, is this the most challenging thing I can share with someone. I always talk about we should put something the stage that feels so personal and challenging to talk about. If we can overcome that challenge, it will help people see their own lives. We found the audience didn’t want to just see it, but wanted to respond. To ask questions, disagree, agree. I think it’s the way that I, as an artist, can share my work – to allow people to get a chance to experience it and also respond.

The show was presented in 2015 as Invisible Thread in New York at the suggestion of producers to see if a change of title would make it more commercial. What’s the biggest challenge for the two of you in staying true to your instincts while still navigating the world of producers and venues? Does your art need to be accessible?

Gould: That’s a good question. Does art need to be accessible? I think, speaking for me, by its nature, if art doesn’t get shared with somebody and seen by somebody and comprehended by somebody, then I don’t know that it serves much value. I guess I don’t come from the school of “art for art’s sake.” We live in a culture where people don’t go to churches or synagogues. People are retreating from certain ideas of community. So the theatre is the place where communities can come together around an issue that’s hard to talk about and talk about it. I also think art can be challenging and make people go, “huh, what the hell is that?” And that’s what the title changed didn’t do. It made it blah.

What revisions have you made to the show for this production?

Gould: We’ve tried to get the story back down to the gritty truth of it. I think in the process of commercializing the show we had to make some compromises about what we think the story was and is. We decided to restore old impulses and text. When we get stuck we ask, “why didn’t we write this song?” And that leads us down the right path. We’ve written new songs. We’ve added a lot of new music. We’re going to do a more experiential piece so the audience will be right in the middle of the action. This story wanted to feel like it was right on top of you. You want to see the actors sweat and feel their emotions.

Griffin, when the church kicked you out for being gay, what were your thoughts about the church in general and how lacking in any perspective of love that represented?

Matthews: We were just living in a different time. Not to say it isn’t happening today. But when it happened I didn’t have a voice. Social media was very new. When it happened to me I only had the people in my cell phone and my circle. It was really painful because I didn’t have any way to express myself except to speak to the church community and get them to rally around me. It was devastating.They are still fighting these antiquated ideas, but I think it is shifting.

Matt you spent time in the Sahara and Griffin had his time in Uganda. Both seem about as far away from musical theatre as you can go. Where do you think you might be without these experiences?

Gould: I would be an ensemble member in The Lion King. I tell students all the time that you should not stay home after you graduate from college – especially artists. I think it is important to get some perspective. For me it was a very conscious choice as a senior in school. I don’t have anything to say. I should learn something about the world and maybe do some good.

Griffin, of all the countries you could have chosen, why did you go to such a virulently anti-gay one?

Matthews: I didn’t know that at the time. Part of the thing I loved about that time is there was a certain amount of naivete that I encourage travelers to experience. I’m so glad that I didn’t know all the things I know because I never would have gotten on the plane. When I found out Uganda was a tricky country to be in, it made me dig in my heels even more. I’ve spent time over the last 12 years visiting Uganda every year. We’ve become friends with the LGBTQI community and have become allies with them.

You are now 11 years into this project. What has Witness Uganda taught each of you and how have you each changed with it.

Matthews: It opened my eyes to the fact that we need more storytellers of color, directors of color, producers of color. I think what I’ve learned inside of it is that sometimes you have to rally your own troops to get around your own story. In meetings with investors I was never seeing myself across the table. It becomes a challenge to have your work done and heard out there. I think the great thing that has come from the nastiness of this [Trump] administration is when I hear African American civil rights leaders say “there were white people right next us.” It has become such a humbling and inspiring lesson.

Gould: I think that nothing worth doing in life is easy. That we work in a really crazy industry and the balance of art and commerce is really tricky to navigate. It’s tough to make a musical about a gay black man who went to Africa to find his place in the world. I think the lesson is this is what we want to do. We want to tell hard stories that have an impact on audiences. I think it has brought us closer as a couple and not because of the successes, but more because of the moments of deep trial and hardship and the moments when we thought it wasn’t going to happen.

Production Photos by Kevin Parry/Courtesy of The Wallis