“I arrived here three years ago from Australia where I was head of the National Institute of Dramatic Art in Sydney,” says director Jeff Janisheski. “A little while after I read a New Yorker article on experimental opera in Los Angeles and it mentioned Long Beach Opera. At the same time I read about a group at Cal State Long Beach, a support group for students who were formerly incarcerated. And I thought about In the Penal Colony.”

And thus the collaboration between CSULB, where Janisheski is the Chair of the Theatre Arts Department, and Long Beach Opera came to be. This weekend marks the final three performances of Philip Glass’s In the Penal Colony, a 90-minute opera inspired by a short story written by Frank Kafka that was first published in 1919. The libretto is by Rudolf Wurlitzer.

The production has been very successful. Every performance sold out. Which no doubt pleases Janisheski, who has more than just artistic aspirations on his mind with this project.

“I read about the prison industrial complex, that’s an urgent issue and something we should tackle. This comes from the massive rise of prisons and the money spent on them. They are a new form of slavery in America.”

Janisheski believes that we no longer use prisons as a place for potential rehabilitation, but rather as profit centers preying on those who cannot afford good representation.

“There are many injustices being done,” he says, “especially by those with money and power. Prisons don’t solve the problem of crime and they don’t do anything for the victims of crime. It just perpetuates the idea of retribution. And the poor get imprisoned and the rich escape.”

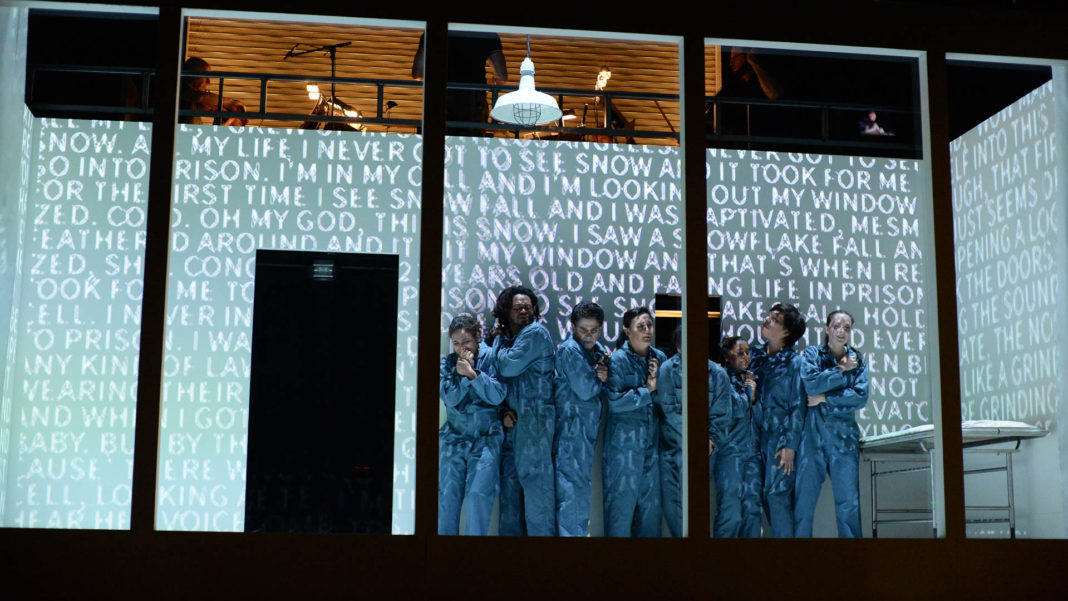

As part of his concept for In the Penal Colony, Janisheski incorporates dialogue from multiple formerly incarcerated students into the work.

“We’re not disrupting or changing the opera whatsoever. It’s still the Philip Glass opera. Dramaturigcally it makes complete sense. If you look at the history of this opera, the very first performance in America wove in Kafka’s short stories. There’s also a version in England that took verbatim text for prisoners and wove it in. When you see it, this insertion happens within the instrumental versions already in the score. We’re not rearranging it or changing the libretto.”

Though the composer wrote this opera 19 years ago, it is not regularly performed, nor has it been embraced the way much of Glass’s other operas have been.

“It’s a more brutal piece of his,” offers Janisheski. “It’s not a pleasant one about a more palatable subject like Gandhi. It’s about a holding cell where people are tortured and there are long descriptions of that in the opera. It’s challenging dramatically and thematically. But that’s the point of it. We need to examine this very challenging issue of the rise of prisons, the increase in prisons and they way they abuse and destroy people. Prisons erase people and try to erase problems, but they just hide social problems. They hide them from our view and this piece is about exposing all those problems.”

Not everyone is going to agree with Janisheski, but he’s not concerned with using theatre as an olive branch to those with opposing views.

“I’m taking a very strong stance here,” he says unabashedly. “I’m clearly on the side of the people who are in prison and who have left prison. People who realize this is a larger system, like the machine in the Kafka story that is really bent on destroying people and not on justice. The audiences will have their own viewpoint.”

He’s not stifling those other viewpoints, either. The audience will have the opportunity to express their own opinions as there are pre-show and post-show talks.

“The role of art is a springboard towards conversation. We sit in the dark and we watch something and we’re part of a community. Afterwards we can have a civil discussion. It might be passionate, but it will be civil. But that’s what art can do. I don’t want the piece to shut down the conversation.”

What Janisheski loves is that whatever your point-of-view, art can be a conduit for conversation.

“For me art is a very wide church. Art can be entertaining. What did Matisse say, ‘I make paintings for the tired businessmen.’ What was that quote? There is some art that is entertaining, some that is beautiful. There is art that is political. There is art that is provocative, that is disturbing. Art can play many roles in our society to address the multiple aspects of our society and our human connection. It doesn’t have to have one narrow role.”

For all of his personal opinions, everything for Janisheski starts with the material itself.

“For me the heart of Kafka’s story and Glass’s opera are what you are going to see. It’s about a world of division. The separation between us and them, the rich and the poor. The people who run the machine versus those inside. It’s the people who have a voice versus the voiceless. The Kafka story unfolds word-for-word in the opera with a context that responds to 2019 and where we are in California. This particular university has students who have been incarcerated and are overcoming it and have successfully overcome it. I wanted to learn from and engage with this group on campus. I was moved by their stores. I wanted to allow those voices to be heard.”

Production photos by Keith Ian Polakoff