“It started with an itch of mine to tackle the form of opera,” says artist and dancer and choreographer Adam Linder. “My work addresses all forms within performing arts and quite actively jumps between them. I make costumes, I compose text, I incorporate vocal forms in my works, but I am a dancer at heart; so somehow making an opera was the next card to play.”

So began a series of e-mail answers to questions I posed Linder regarding the opera The Want which opens the CapUCLA season tonight with performances at REDCAT.

The Want was inspired by In the Solitude of Cotton Fields, a play written by Bernard Marie-Koltès in 1985 and first performed in 1987. The play depicts, in very unspecific terms, the dealer/client relationship.

Linder used this play as the springboard for the opera which was composed by Ethan Braun. My initial question to Linder had to do with his first awareness of the play.

When did you first become aware of In the Solitude of Cotton Fields?

As the stars aligned, I learnt of this work by Koltès and it sparked desire to take this play that has always been performed in a conventional way – a very straight theatre mode – and turn it into an opera.

It isn’t often that a new opera is billed by the name of its choreographer. That leads me to believe that this wasn’t a traditionally structured collaboration. Can you tell me how the collective creative process for The Want took place?

Ethan Braun, the composer, and I met because I was looking for the right composer to work with me and as he is an irregular fit for the classical music world, that made him a natural fit for me. Shahryar Nashat, who designed the stage, is a different story. We’ve been in and out of each other’s work for years and he’s my boyfriend. Read the Bomb article; says it all.

I had a strong sense for the direction this opera should take, but it all got developed in the productive manner of leading with this vision whilst allowing enough space inside the working environment for these other artists to do their thing.

What resonated with you about how Koltès depicted the dealer/client relationship and how does that relationship allow you to comment, vis-a-vis The Want, about the world we live in today and the way relationships are bartered?

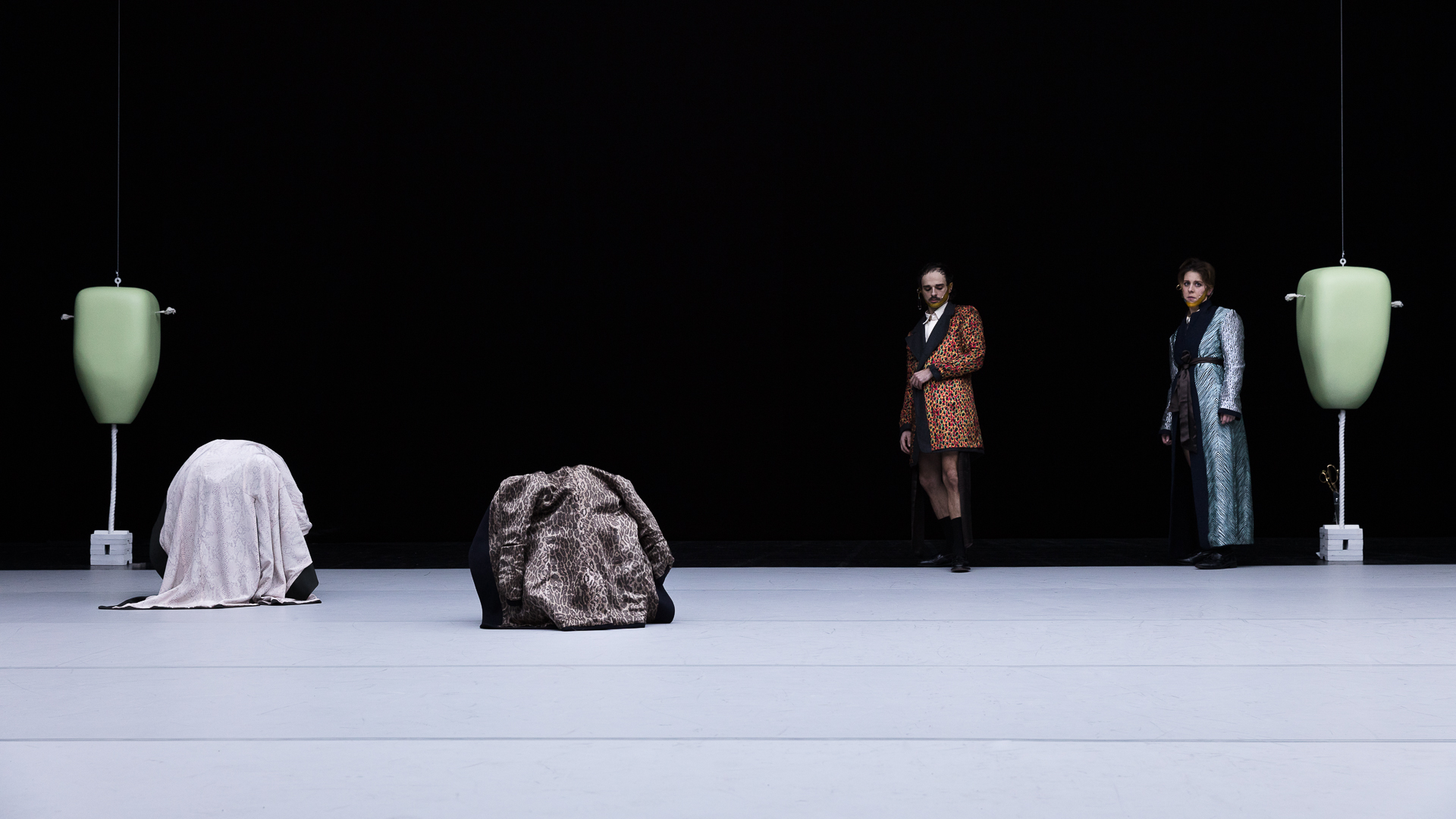

The work in its original form had just two people. My work is a very unfaithful reworking, so there is little of the original Koltès text in my libretto. It has always been staged as a two-person – two guys – play. In the way I have structured the work, Jess Gadani and Justin F. Kennedy are the Offerors, and Jasmine Orpilla and Roger Sala Reyner are the Offerees – but it becomes quite fluid. Just like the original play, it is never determined who wants what from whom and what it is they want and what it is they can offer. It’s always meddling in grey area. But I push the grey area of sexuality, race and gender (and spiritual identification) far more than the original.

You’ve spoken previously about not caring “about disciplines meeting, but about sensibilities criss-crossing.” How does The Want represent a criss-crossing of sensibilities?

Yes I spoke about that in relation to the empty term of inter-disciplinary. When you imagine the whole of a picture or the fullness of an experience, it is necessary to pull from different sensibilities, forms and histories, but it’s a singular approach and in my case it’s one that is foremost a choreographic one.

What excites you about the music Ethan Braun writes – both for this work and beyond The Want?

The fact that he’s from this specialized world of classical music, but has a background in performing and improvising a more jazz inflected repertoire. That he wrote his thesis on Stockhausen. And that he believes in expressivity and virtuosity.

Koltès says in his play that “we move along two distinct planes, and than in the end there is only the fact that you looked at me and that I caught that look or the other way around, and that, from the outset, absolutely the line you were moving on became relative and complex, neither straight nor curved, but fatal.”

Philosophically how do you respond to that line from the play and do you believe this is not just a philosophy, but a realistic way of looks at interactions between two people?

Koltès’ way of handling this politic of relation is to embellish the sense of existential mystery between two people. I think he considers that mystery as being just as expansive as it is fleeting; it could simply come down to catching a passing gaze but it could also unfold in never-ending circles of unnameable ambiguity between two. Koltès acknowledges this insurmountable duality.

For tickets go here.

All photos by Andrea Rossetti/Courtesy of CapUCLA and REDCAT