When a construction site in Dawson, Canada (location of the Klondike Gold Rush) unearthed a lot of film reels in 1978, no one was immediately sure of what had been found. It turned out to be long lost silent movies that included footage from 1917 and 1919 world series games, old one-reel films and more. Dawson was, after all, the last stop as silent movies got sent from one town to another. Filmmaker Bill Morrison made a documentary called Dawson City: Frozen Time. But to tell his story he needed the perfect composer to write the music for his film. He turned to Alex Somers.

Somers is the composer of the score for the currently playing Honey Boy. He also scored Captain Fantastic. Music fans know him as an essential collaborator with the band Sigur Rós. (He and the band’s Jónsi are partners.)

On Friday, CAP UCLA will present Dawson City: Frozen Time Live at the Theatre at the Ace Hotel. The score Somers wrote will be played live by Wild Up who will be joined by a female chorus from Tonality. (To view the trailer for the film, go here.)

Last week I spoke by phone with Somers about this project, his music and what long lost items of his might be interesting to dig up someday. Below are edited excerpts from that conversation.

When you first were approached about this project, what stood out to you as the most interesting things that would serve as inspiration for your writing?

Straight away when I first heard about it, it was a dream project. It was very up my alley. Working with f***ed up looking film footage that was lost and found and repurposed to tell a story. It was in line to how I hear and see things for my music. It was a no-brainer.

How much of a fan of silent movies were you before you were introduced to this story?

Not really. When I come across them I think they are really neat and cool, but I couldn’t say I was a fan. I knew Bill Morrison and was a fan of his work. His signature thing is he only works with archival footage.

The documentary tells the story of films that date back to the earliest days of cinema. Those films are then found in the 1970s and the story is told in this century. How did that vast expanse of time influence your approach to the music?

I wanted to create music that was inherently flawed. The story which Bill told me, which is quite sad, is Dawson City was the furtherest northern point that had a cinema. These prints would be shipped around and it was too expensive to send them back. No one knew what to do with them. That story informed the music.

I wanted to have this thing that you put so much care into it and then disregard it. I tried to do that with the music. I did string and choir arrangements and dubbed them to microcassettes which destroys fidelity. Any chance I could get I tried to disregard the meaning of the music and f*** it up. It was trying to mimic Dawson City. It burned down nine times and was rebuilt every time. People died and lost their homes. I tried to have the music have this creation and then almost be destroyed and then built up.

How then will an ensemble like Wild Up be able to recreate the sound you created for the film?

It’s hard to recreate it exactly. We’re going to get as close as we can. For me the notes of my music are only 50% of the work. So much is about the sound. It should be a nice blend of orchestra, choir, piano, vibraphones and a little bit f***ed up.

There is also a sound design track for the film. It was the first time Bill Morrison had used sound design. That will be treated as an instrument in the performance. Harmonically my music is so simple it leaves space for texture and sound.

Charlie Chaplin, perhaps the best-known of all silent movie stars, said in a letter he wrote in 1918, “It is always the unexpected that happens both in moving pictures and in real life.” Do you agree with him and what was the most unexpected thing that happened to you while collaborating on Dawson City: Frozen Time?

That’s a great question. I do agree with that sentiment. Art and life mimic each other all the time. I’m not sure the most unexpected thing. Every time I would send another version of the score, Bill would be, “It’s got to be darker. More low cellos and basses.” He wanted to feel the rock bottom of this town and the films.

If someone years from now was excavating land and they found some of your material, what would be something you’ve lost that might be fascinating for future generations?

That’s cool. I think some of my microcassette tapes. I’ve recorded since I was 14 and I was playing guitar and writing songs and archiving them. I had fourteen of these little cassettes. I’ve lost most of them. There’s all kinds of things on there and weird moments from my life growing up. I always kept that microcassette recorder around. That would be neat for people to find that stuff because it would sound pretty weird.

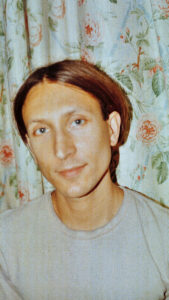

Photos of Alex Somers courtesy of CAP UCLA.