It seems like a Herculean task: documenting the history of music in New Orleans in less than two hours. After all, music in the Big Easy goes back hundreds of years. The task, however, did not seem as daunting to filmmaker Michael Murphy. The end result is his thoroughly enjoyable and informative new film Up from the Streets: New Orleans The City of Music. The documentary has the first of three screenings at the Pan African Film Festival and Arts Festival on Friday. Given this film is a love letter to the city he loves, it is appropriate that first showing is on Valentine’s Day.

Up from the Streets, which features musician Terence Blanchard as both a performer and the on-camera narrator, was originally planned to be part of the celebration of the 300th anniversary of New Orleans. Like many a documentary before his, Murphy wasn’t able to get the film done by that time.

Earlier this week I spoke by phone with Murphy about the city he loves, how Louis Armstrong is the foundation of much of the music from New Orleans and about the future of the city itself. Here are edited excerpts from that conversation.

In the film Herbie Hancock says, “New Orleans has been the heart and soul of this country for generations.” Do you think that is common knowledge?

I don’t. Why not? I can only tell you from my own personal experience. Being an independent filmmaker and trying to pitch film and programs about my city, there was always, I consider it almost like a knee-jerk reaction that “New Orleans is great, Michael, but your city’s music almost belongs in a museum.” One of the first questions asked by potential distributors was “How are you going to make this music still seem relevant?”

I knew how I was going to do it. I’ll start with the founding of the city and take it all the way up to bands of today like Tank and the Bangas and Terence Blanchard. Like Terence says in the film, “You can walk down the street and it sounds like they have an influence of Louis Armstrong and they don’t even know it.” You have one eye in the rear-view mirror and one eye looking forward.

If Louis Armstrong were to hear Tank and the Bangas, would he see or hear his legacy in that music?

I’m not sure if he would see it immediately. If he talked to the band members he might pick it up. I think I would have to be a musician to really understand that.

In the film Jelly Roll Morton and Louis Armstrong are called by Preservation Hall Creative Director Ben Jaffe “punk rock of their time.” Obviously Armstrong changing a lyric in “When It’s Sleepy Time Down South” to “When It’s Slavery Time Down South” is pretty punk, particularly when he did it. What else makes them punk?

Going back to the 1980s when I started doing this stuff, [Murphy has filmed Jazz Fest in New Orleans for nearly 20 years] there were a lot of musicians who didn’t understand Louis Armstrong. It was that negative association that he was an Uncle Tom sort of thing. As I became more involved with the musicians over the years and Terence says it beautifully, this guy was on the cutting edge. This guy was taking the tradition of New Orleans and he was adding things like solos that were keeping perfectly in time with the song, but suddenly you have this incredible solo that breaks out. Harry Connick Jr. talks about the importance of improv and a lot of that improv comes from Louis. I can see what Ben was talking about. He was breaking out of the traditional New Orleans sound.

You have a lot of unique performances of songs in the film. How did you select the artists and the songs and will there be a life for those recordings outside the film?

The selection of the songs was rather difficult. Initially I had 200 songs, then I got it down to 100, then 50. But I was always bouncing ideas off Terence and throwing out a song, trying to see what encapsulates as best as possible all this music that comes out of the city knowing I couldn’t include everybody. In terms of other use, there have been people asking if we are doing a CD. That is something we are going to pursue.

Hurricane Katrina devastated the city and you include it in the film. While watching it, I got the sense that future generations may never get to experience due to global warming. Did you consider that while making the film?

I’m not sure I thought of it like that, but I will tell you the Katrina segment I built into the film, I can admit, I still cry every time I look at that segment. I get really emotional. I’m kind of doing it right now.

I was here. I was stubborn as hell. At the last minute I got out, but when I came back the destruction was unbelievable. I still carry that particular concern, but I have that concern on a global basis.

Louis Armstrong once said, “Every time I close my eyes blowing that trumpet of mine, I look right into the heart of good ole New Orleans. It has given me something to live for.” What has New Orleans given you?

Oh my God. New Orleans have given me a very deep appreciation of life. And trying to live life to the fullest. As a young kid we didn’t have air conditioning. It was hot in the summertime. We would always sleep with our windows open. I have memories of laying in bed and I would hear somebody practicing an instrument. It could be a piano, a horn or a drum. But every night you would hear from different corners of the neighborhood. I would fall asleep listening to that. That’s New Orleans right there.

Up from the Streets screens February 14th at 9:30 PM; February 19th at 4:00 PM and February 20th at 9:25 PM at the Cinemark Baldwin Hills Crenshaw Plaza Theatres. For tickets go here.

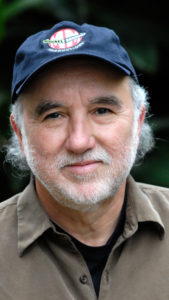

Main photo: Terence Blanchard in a scene from Up From the Streets (All photos courtesy of the filmmaker)