Perhaps no one was more surprised by the popularity of the recent Quarantine Edition of A Chorus Line than the Tony Award-winning co-choreographer of the musical, Bob Avian. The video finds cast members from the 2006 revival performing the opening choreography within the confines of social distancing.

“I love it! Someone in the cast started it and it just went like a snowball,” he said by phone last week. “They were doing it for their own amusement and it just caught on. I was so proud of them.”

The popularity of the video only mirrors the passion people have for A Chorus Line. The timing for Avian couldn’t be better as his memoir, Dancing Man: A Broadway Choreographer’s Journey, was recently published.

It was while dancing in a production of West Side Story that Avian met the man who would become his best friend and collaborator, Michael Bennett. Together they would work on such landmark shows as Company, Follies, Promises, Promises, A Chorus Line, Ballroom and Dreamgirls. After Bennett passed away in 1987, Avian would continue working on musicals including Miss Saigon, Putting It Together, Sunset Boulevard and ultimately directing that revival of A Chorus Line.

We began our conversation by talking about that iconic choreography that opens A Chorus Line. Here are edited excerpts from the interview. Comments have been edited for clarity and length.

“I Hope I Get It” has such a distinctive style. What inspired that choreography and why do you think that opening remains as vital today as it was in 1975?

What makes it special is Marvin’s [Hamlisch] music because it’s in 6 not 8. Most dance combos you count in 8. Being in six gives it a curve that’s subliminal. The attack is different and you feel it in your gut. I think that’s the root of what makes it so special. Michael did that.

You say in the book that at the age of 10 or 11, even without training, you knew you could dance. Was there one moment that made you come to that realization? Your own “I Can Do That?”

Being home alone and putting on a record player of the things I liked best and I would start dancing around and see where it took me. Being alone you have that freedom. You didn’t know what you were going to do and you let it pour out of your soul. Luckily we had a big living room. My life was concealed because I was gay and my parents were ethnic and it was a big no no. When I put on the music and closed the door and was my myself, I could be who I was and not have any censors around me.

Follies at one point had two men in drag during “Buddy’s Blues.” In 1971 that must have been played as a stereotype. What is the process where ideas like that find their way into a show and as a gay man how did you feel about it?

When we went into the show a lot of the score hadn’t been written yet. Stephen Sondheim needs to see things first. He writes his best showstoppers when he’s out of town. Whether “I’m Still Here” or “Send in the Clowns” or “Being Alive,” it’s because he sees the show. That’s part of his process. I don’t know. It just comes and you roll with it and you do the best you can.

When you and Michael accepted the Tony Award for Best Choreography for A Chorus Line, you said, “This is the professional high point of my life.” Michael said, “Michael Bennett is Bob Avian.” What meant more to you in that moment, winning the award or Michael’s acknowledgement of the importance of your contributions?

Michael and I were so close. We were brothers, never lovers. Everything we did we did together almost 24 hours a day. We were on the phone when we weren’t in the rehearsal studio. It was his ultimate compliment to say, “I love you Bobby.” It’s so much easier and nicer to share success and failure with someone.

Both Sammy Williams (who originated the role of Paul in A Chorus Line) and Baayork Lee (who originated the role of Connie in the same show) told me stories about how cruel Michael could be.

If you are successful and you are working on a multimillion dollar musical the pressure is enormous. You have to have strong shoulders to handle this. The one fear you have is are they going to fire me.

In many cases it’s about their anger in themselves. I find myself getting so angry at a dancer or a group of dancers when I’m unhappy with myself. It’s aimed at me, but it comes out of my mouth and at them. It’s like using the wrong color on a canvas.

Miss Saigon, Sunset Boulevard, the London revival of Follies and many more are part of your post-Michael Bennett career. Some artists say they don’t choose the work, the work chooses them. Is that your point of view?

Well it happens to me. I had no idea what was going to happen when Michael died. He talked me into doing Follies in London on his deathbed. I didn’t want to do it again. I kept saying it’ll never be the original production. What it gave me was Cameron Mackintosh. He just took to me and globbed onto me and dictated the rest of my career.

Michael was clearly so important to you. What do you think he’d say if he could see what you’ve done with your life and career since his passing?

Our respect for each other was so honest and so real. We exposed all our inner souls to each other. I was lucky to have that relationship. I think he would say, “Well done, Bobby.”

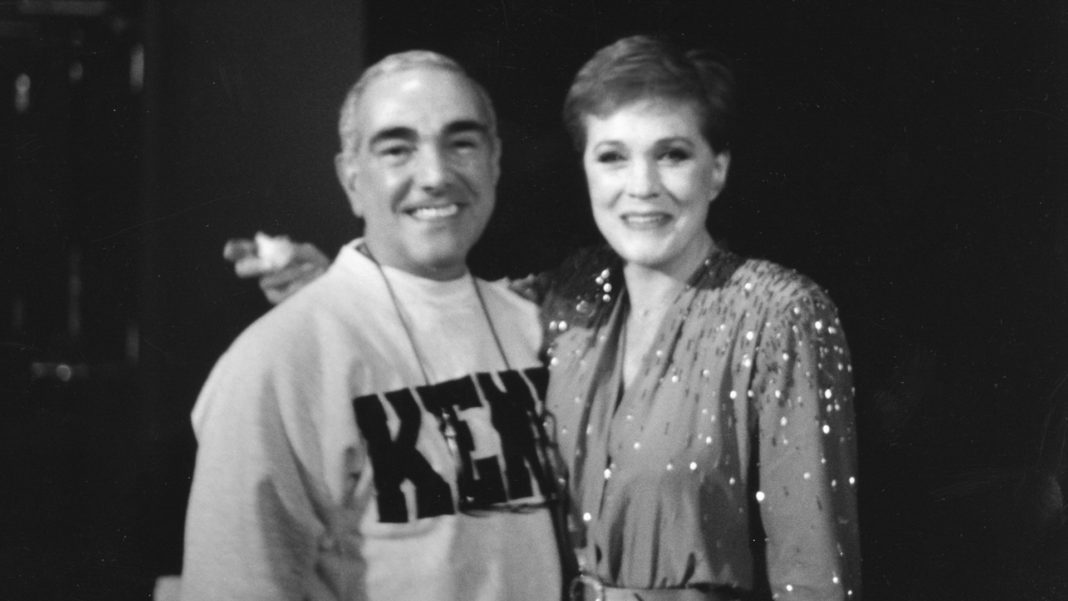

Photo of Bob Avian and Julie Andrews courtesy of Bob Avian