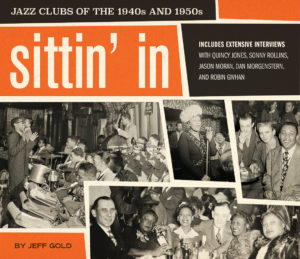

It would be foolish to label Jeff Gold as just one thing. He’s a writer. He’s a former music executive. He’s a music historian. He’s a memorabilia collector and seller. And he’s a cultural anthropologist. Just take a look at his recently published book, Sittin’ In – Jazz Clubs of the 1940s and 1950s.

A collector reached out to Gold and said he had photographs that were taken by the in-house photographers at multiple jazz clubs during that time. Gold met with him and was immediately struck with the idea of a book. Though he had sworn off ever doing another book after publishing 101 Essential Rock Records and Total Chaos: The Story of the Stooges.

“I put them on my bookcase and engaged in a staring contest for six months,” Gold told me in a phone call recently. “Periodically I’d Google to see if I could find other photos and I looked up books on other jazz clubs. They are such an obscure topic and so evocative and there was so little about them anywhere. They stared me down and won.”

If you read Gold’s blog posts on his website, RecordMecca, you wouldn’t think the man who spent over 40 years getting a rare Bowie album signed by the singer and his band would be so passionate about jazz.

“When I started it I knew very little about jazz clubs beyond what an obsessed music fan picks up along the way. Skimming 40 books and hundreds of hours on the internet, I’m kind of an expert.”

A few things surprised Gold during his journey of writing Sittin’ In. The first is that you rarely see photographs of the audience. It’s usually the performers who are shown. When he writes about Bop City (a Manhattan club based in the Brill Building), he quotes a reporter for New York Age as saying, “Outside of Ella Fitzgerald, the great performance was that put in by the audience, the greatest mixture of humanity this side of the Casbar (sic).” It forced him to ponder why the audience is so rarely considered.

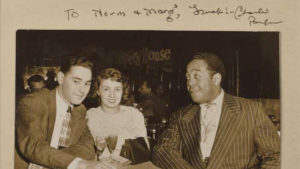

“This turns the camera around on the people who watched the performances. In almost every case they look like they are having a great time, even if in some cases you’re in the middle of World War II and there’s racism going on. But this was an escape from it all. The interesting thing is some pictures have artists posing with the fans. These are primordial versions of celebrity selfies. When would you see earlier examples? I couldn’t think of any.”

There’s also the issue of race which is unavoidable looking at the photos.

“You have African American performers posing with white audiences and that was something you didn’t see in any other circumstance,” Gold says.

In an effort to understand more about how these clubs operated, he interviewed Quincy Jones and Sonny Rollins. Gold was surprised when Jones told him he didn’t sense any racism when attending the clubs he could get into (some of them were segregated) nor when he was performing. Which prompted me to ask Gold whether he thought jazz clubs laid the groundwork for tolerance.

“That’s kind of a heavy question I don’t know if I have an answer to it. One thing that came out for me is context and time is everything. There was a completely racist club I have a portfolio from in St. Louis called Club Plantation. Their advertising said, ‘strictly white patronage only.’ That was a selling point for them. Oddly enough there was a Black-owned club in Watts [an area of Los Angeles] called Joe Morris’ Plantation Club. That is a reprehensible thing in 2021, but in the 40s it didn’t seem to be objectionable to Black people because it was successful and [Black-owned.]”

During World War II, when most of these clubs were featuring swing music that allowed patrons to dance the night away, the government added a cabaret tax to raise money for the war effort. This forced the club owners to find a way around the tax and the end result lead to a whole new style of jazz.

“Swing was the dominate music. There were some musicians who were getting tired of the regimented and charted swing music with one solo per show. Those people, Charlie Parker, Thelonious Monk and people like that, experimented with what becomes bebop. Someone realizes if you hire the bebop guys it is music you listen to and people don’t dance. They can pay less people. This cabaret tax ends up being the thing that causes these owners to book bebop.”

Amongst Gold’s collection is one of John Coltrane’s saxophones, who performed bebop early in his career. So it was appropriate I ended our conversation by asking him about something the musician had said. “I’ve found you’ve got to look back at the old things and see them in a new light.” I wanted to know what the new light is Gold has found by looking back at these jazz clubs from the 40s and 50s.

“The new light is not just a new light, it’s a light. The fact that if people have ever seen these photographs it’s maybe one or two of them. There’s not been a collection like this published ever. It’s a niche phenomenon. It’s an opportunity to look at issues like jazz, the race relations in America, American history and the laws of unintended consequences through a different lens. I was the guy able to illuminate this phenomenon.”

Main Photo: A soldier, Joan Davis and Duke Ellington at 400 in April, 1945 (Photo courtesy Jeff Gold)