On September 8, 1971, the Kennedy Center in Washington, D.C., opened its doors for the first time. To celebrate the grand opening, Leonard Bernstein’s Mass was given its world premiere. Subtitled A Theater Piece for Singers, Players and Dancers, there were many people listed on the title page of the program: Alvin Ailey, Bernstein, director Gordon Davidson, Stephen Schwartz who was credited with additional text, producer Roger L. Stevens, two choirs and more. Not included was the young man who would be playing The Celebrant, the character at the center of the piece. That man was Alan Titus.

The baritone was a fairly recent graduate from Juilliard and had yet to establish himself as one of the premiere opera singers in the world. At that point, by his own definition in a recent interview, he knew exactly what Bernstein was looking for when he the two met.

“Young,” he said via a Zoom conversation before letting out a big laugh. “I was fresh out of Juilliard. I brought my guitar to the audition. I was dressed in a green suit, just like The Celebrant. The light went off and I sang an old Harry Belafonte song called Waterboy a cappella. I think that was kind of a key moment.”

A moment that put him squarely into the middle of a high-pressure situation for the composer. Bernstein had achieved monumental success (West Side Story, music director of the New York Philharmonic, best-selling records around the world.) A lot was riding on him, least of which was the fact that Jacqueline Kennedy Onassis had personally asked Bernstein to write this mass as a requiem for her fallen husband, President John F. Kennedy.

Titus recalled his collaboration with the maestro.

“The process was interesting because, first of all, he was the composer. As a composer he fed me how he wanted it to be interpreted. Like A Simple Song. He pulled up a chair in front of me and said in his soothing voice and I just imitated. So what you hear on the record is Bernstein traveling through me.”

Was he concerned that Bernstein was basically telling him how precisely to do his job? Not in the slightest.

“Are you kidding? You know, if a God talks to you, you follow it. At Juilliard we learned to honor the composer’s wishes. So instead of reading it off the paper, I had it coming from the creator’s mouth.”

The reason for our conversation is the release last week by Sony Classical of a remastered version of Mass that also includes a 140-page book filled with memorabilia from those heady days. Titus, who was brought up Catholic, felt a symbiotic relationship with Bernstein’s work.

“I was very interested in psychology and studied a lot of Freud. At that time I started getting [into] Carl Jung. I had been an altar boy. I knew the [Catholic] mass by heart and I knew what I felt in the mass in my own worship. So I just brought all those feelings and I sort of felt like a citizen priest.”

A citizen priest might be the best way to describe The Celebrant. He’s also a troubled one who has his own crisis of conscience during Mass that results in a breakdown.

The 14-minute aria called Things Get Broken is arguably the most powerful moment and one that requires tremendous discipline as Titus learned.

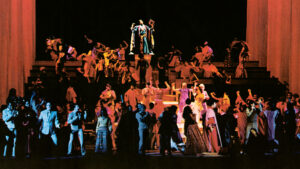

“It was a massive undertaking. The greatest moment in the piece is the apotheosis after the Sanctus and you get everybody dancing on stage. The Celebrant mounts the steps with the monstrance and suddenly [you have] the apotheosis of this piece. You have the history of the Jewish religion, from Moses to Christianity. Suddenly The Celebrant does turn into a kind of Moses figure in which he throws down the tablets that God, supposedly with his own finger, wrote on stone. So after Things Get Broken, it’s not only a mad scene. It’s how Moses must have felt after he threw down these sacred tablets among the Israelites. At that one moment that’s fantastic: the correlation between Judaism and Christianity.”

Bernstein wasn’t as exacting in his request for a specific performance from Titus for Things Get Broken, particularly when it came time to record Mass.

“When a good singer works with a great conductor you have a synchronization of mind. I was totally in sync with Lenny’s mind. He heard what he wanted through me. So he gave me permission to go deeper into whatever emotional reservoir I had to bring it out. Allowing you to express these emotions to your deepest core opens you up for all future projects because you know I can go this far. I didn’t listen to it for 50 years. I listened to Things Get Broken and [was] reminded we did it one take. I mean, that was the level of concentration we had then. We were all in sync.”

That synchronization began to expose some problems that ultimately lead to Titus not singing the role of The Celebrant as more performances in different venues were booked.

“When we parted ways it was because I started seeing The Celebrant as Lenny himself. And he called me up to the box when he was at the Philadelphia Academy of Music. I didn’t want to do Mass all my life. I was always interested in opera. I started doing The Celebrant like Lenny Bernstein and what I had seen behind the scenes and how the musical business was fought. I tried to bring the man to The Celebrant. He said, ‘Listen, we’ve lost your innocence.’ I felt like saying, ‘You think?'”

But that moment didn’t happen for several months after Mass was first performed on that September evening. Titus recalls exactly what happened at the curtain call.

“At the end of Mass at the premiere, they brought Lenny out on stage. And, of course, he was just a ball of tears. He was so emotional and crying. I looked at him and I had this colorful guitar strap. I went over to him and I put the guitar strap around his neck. Well, you could have carried him offstage. It was, I think, one of the most beautiful moments of the whole project.”

Bernstein’s Mass is available on Sony Classical. The Kennedy Center will have a 50th Anniversary production of Mass September 15th-17th, 2022. Will Liverman will sing the role of The Celebrant.

All photos by Don Hunstein/©Sony Music Entertainment

Correction: We originally quoted Alan Titus as saying he spoke with Leonard Bernstein at the Philadelphia Museum. He actually spoke with him at the Philadelphia Academy of Music. Cultural Attaché regrets the error.