My friend Bruce Schultz is fond of using the expression, “Sometimes you eat the bear. Sometimes the bear eats you.” That definitely suits my relationship to technology last week when it definitely ate me during my interview with the amazing baritone, Davoné Tines.

We spoke by phone last week as he was driving with Yuval Sharon. The two men had just spent time at Interlochen Center for the Arts in Michigan. We had a terrific conversation. Tragically the app I was using only recorded the first ten minutes of that call. Thankfully those first ten minutes were rich – as you will see.

Tines is a Juilliard graduate and a fierce advocate of works by new composers. He originated the lead role in the world premiere of Terence Blanchard’s Fire Shut Up in My Bones in 2019 at Opera Theatre of St. Louis. He’s also performed compositions by Kaija Saariaho, David Lang, Matthew Aucoin, John Adams and more.

His work to confront racism is best represented by The Black Clown, a music-theater piece he created with Michael Schachter that was adapted from Langston Hughes’ poem of the same name. Tines has also become a leading proponent of the work of composer Julius Eastman whose works have been gaining in prominence over the last decade.

Eastman was a minimalist. He didn’t adhere to the style of contemporaries like Phillip Glass. Eastman’s music was aggressive. It was political. It was, at times, confrontational. And it was rarely written down. Much of what he did write down was sadly scattered to the winds as he battled homelessness and drug addiction.

One of his most significant pieces is The Holy Presence of Joan D’Arc which is being presented in a film starring Tines that is part of this year’s The Tune in Festival from CAP UCLA. The film closes out the on-line festival on Sunday, November 7th.

There’s a prelude to The Holy Presence of Joan D’Arc which finds the soloist performing a series of repeated phrases over the course of 13 minutes.

Tines has performed the pieces several times, including a performance in 2017 at Zipper Hall in Los Angeles.

Early in our conversation I asked him how his relationship to the work has evolved since that time.

“When I was first doing it, it was more about the visceral aspects of surviving through those 13 minutes. Trying to give those short, important words, as much support and clarity as I could. To have the interpretation of the piece come from the actual doing of it. Meaning, he organically outlined things to break down over time or lower in register and stretch out in time. And now that I’ve had that visceral experience a number of times, it’s like I have a body or emotional memory of where those places are.

“Doing the piece, it’s not exactly exhausting, but I definitely do feel the kind of tension that I think Eastman is trying to invite the performer into. So I can grow into the piece and in other ways. One way has been to focus very intently on what I think the raison d’etre of the piece is where he says, ‘When they question, you speak boldly.’ That sentence is, I think what the entire preceding eight and a half minutes is building toward.”

Tines went on to illuminate what Eastman was doing with The Holy Presence of Joan D’Arc.

“Eastman is inviting everyone into the role of Joan of Arc and then giving the same instruction that’s poured fourth through her own spiritual ancestry into our current time. So realizing and sitting with, more deeply, what it might mean to try to inform people in the larger trajectory in history to speak boldy and to understand how my own personal values align with that. I see the piece as a conduit for delivering a message that resonates within myself, but was also set forth by an ancestor.”

In notes before the premiere of The Holy Presence… Eastman wrote, “Dear Joan: When meditating on your name, I am given strength and dedication. I shall emancipate myself from the materialistic dreams of my parents. I shall emancipate myself from the bind of the past and the present. I shall emancipate myself from myself.”

Tines agrees that those thoughts seem particularly timely as we try to extricate ourselves from the trauma of the last nearly two years.

“It seems like even listing a lot of things that are, perhaps, secondary to one’s existence and, I think, maybe people articulate their lives or find their identity through many things that he’s listed. But maybe he’s getting at the idea that it’s important to allow those things to fall away and see what actually remains there. One’s self from one’s self, I guess, is one of the most nuanced ones. Maybe releasing the picture of what one feels one is and trying to actually allow some reality or some sheer engagement with reality.

“Given the reality of the pandemic, as you say, I think we’ve all had at least some encouragement, if not space or impetus, through violent and intensive means to do that sort of work.”

There was so much more of our conversation that, like many of Eastman’s compositions, remains but a memory. But I began my interview with Tines by asking him about something else Eastman had said and it seems the most appropriate way to conclude this story.

Eastman said in a 1976 interview “What am I trying to achieve is to be what I am to the fullest. Black to the fullest. A musician to the fullest. A homosexual to the fullest.” How does performing his work allow Tines to do the same?

“It allows me to do the same because our identities are deeply aligned in that way. All of the aspects of identity that he outlined, I also embody. So by being able to realize his words, I’m able to be very closely in conversation or community or connection with his aspirations.

“I’m meaning there are a lot of times where, you know, reference for a work is somewhat removed from you and it’s your job to figure out how to embody that. With Eastman’s work, it’s really a beautiful opportunity for me to do something that kind of pulls a certain specific identity along or finds something that I’m more closely connected with.”

To hear a rare interview with Julius Eastman, we suggest you listen to this 1984 interview he did with David Garland.

CAP UCLA’s The Tune In Festival runs November 4th – November 7th. You can find the full schedule here.

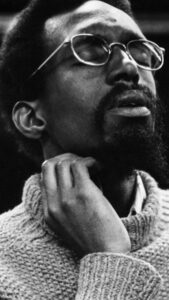

Photo of Davóne Tines by Bowie Verschuuren/Courtesy CAP UCLA