Blue Note Records has long been considered one of the greatest labels for jazz music in the world. Artists such as Art Blakey, John Coltrane, Miles Davis, Thelonious Monk, Lee Morgan, Bud Powell, Sonny Rollins and Jimmy Smith recorded with the label in the 1950s. Any enterprising musician who is given the opportunity to comb through that library is faced with an embarrassment of riches. Such was the case with Makaya McCraven.

McCraven, who calls himself a beat scientist, is a drummer, producer and one of the most successful artists to mix the past with the present and jazz with hip-hop to create new sounds that are both of the past and looking forward.

His latest project is Deciphering The Message. The album, also on Blue Note Records, finds contemporary artists Matt Gold, Marquis Hill, De’Sean Jones, Jeff Parker, Junius Paul, Joel Ross and Greg Ward adding new beats and music to classic tracks by Blakey, Clifford Brown, Dexter Gordon, Hank Mobley, Horace Silver and more.

Last month I spoke via Zoom with McCraven about the album, his view on the past meeting the present and if that pairing can help bridge the ever-widening distance between people in 2021. What follows are excerpts from our conversation that have been edited for length and clarity.

In late 2019 you said, “It’s a crazy time to be alive. There’s a crazy craving for something visceral, something honest, something vulnerable from art.” So much has changed in the two years since you said that. How would you describe the time we’re in now?

It feels like we’re in a completely new world. But I think even more so than ever, you know, there is a feeling that people don’t want the bullshit. They don’t want this life anymore. They don’t want the superficial anymore. Increasingly people want and need a hug, a good talking to, a dose of reality. Something that’s not just fake. I need a dose of of of something real, you know? It’s difficult. It’s crazy. It’s challenging times.

When you embarked on this project, what did you want to accomplish?

In this world where people are listening to individual songs now, I have wanted to make albums. I want to make a record and not a collection of songs and definitely not a collection of beats on a project like this.

There are definitely some central themes dealing with the past and present. One thing I connected with is you look at the people who created this music they were the innovators. They were young people. I think often we look at as this old music. It’s all under these terms of the elders and whatnot.

I’m remixing and bringing things into the modern place and having guys like Joel Ross and young musicians and players that are doing things now, interacting with the youthful nature of that music.

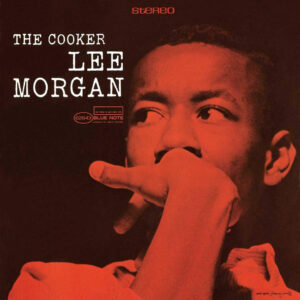

You look at Lee Morgan and Herbie Hancock and Hank Mobley. These guys were like 20 years old and 18 years old. Lee Morgan was 21 when he died. The amount of influence that he gave to us and how he changed the music – now it’s part of the fabric of the sound of contemporary modern music. And so to interact with that with young musicians, with the fresh ideas and bring a light to the innovative nature of this old music celebrates the music and creates something that has some symbiosis.

Jazz tracks have often been sampled but as a backdrop to the new track. On Deciphering The Message the classic tracks seem to live comfortably next to the new music. They aren’t subservient to what you’ve created.

I definitely wanted there to be playing on the record. I didn’t want to just make these small beats. I wanted to make music out of it as well. And I appreciate that comment.

There has been a framing of jazz in a way for sometime where like it’s not for young people. It’s not cool. It’s not hip. It’s not funky. If you’re going to be a jazz musician say goodbye to your career.

I always want to push back on that one. I think the word jazz is wholly insufficient to really talk about the phenomenon of what we’re dealing with. This is music of innovation. This is music that’s hip and bad ass, you know?

A lot of the tracks you selected come from the bop, hard bop and post-bop era. What made that particular style of jazz so attractive to you for this album?

When I went about picking tracks a lot of it was organic and digging and just listening to stuff. I had a number of themes and ideas that I was working around when I was trying to conceive what the narrative was going to be and how I wanted to do it. But at the end of the day the music kind of just helped me bring it together. And you know, from this hard bop era, I did find a lot of these tracks.

Finding a lot of great little vamps in intros and and particularly with the writing of like Horace Silver and Kenny Dorham. There’s a lot of really catchy moments and catchy things that I found just spoke to me. As I started to piece it together, it just got a sound and that kind of came throughout the whole thing. If it sounds right, if it feels right, then I’m on board.

In an interview you did with Ayana Contreras you said “Nothing ever is what it was.” How does that philosophy influence your work and how you live your life?

The way that the world unfolds is within chaos and unpredictability. You know we are all improvisers. It’s a given in the universe that we are out of control. We don’t have full control. We can create as much structure as we like and we can try to maintain as an individual and within society. But we are all subject to the chaos around us and having to improvise and be ready for the unknown. And to me improvisation in jazz and music, in this musical sense, is just an expression of the universe that we are living in.

I’d like to conclude by asking you about something the legendary Dexter Gordon said. “In nuclear war all men are cremated equal.” As polarized as society is today, what role can and should music play in helping us recognize that we’re all one people?

I think music and art in general can disarm even the worst of us in one way or another and transform it into another place where we can have collective experiences that are not bound by just our word or ideas.

Particularly like with this music that’s instrumental. I think there’s something with instrumental music that’s really special because we’re not dealing with the literal word. We’re not dealing with the lyric. We’re dealing with an abstract thing that we can experience beyond language, border or whatever. I hope that the work that we do as musicians and artists has a strong and profound place in society to help open the minds and change the hearts of of people who are suffering and angry and all of the above.

Photo of Makaya McCraven by Michael McDermott (Courtesy Big Fish Booking)