This weekend the Pacific Chorale will be joined by the Pacific Symphony for a performance of Maurice Duruflé’s Requiem, Op. 9. Also on the program is The Notebooks of Leonardo da Vinci composed by Jocelyn Hagen.

It’s a large-scale work that, in addition to the chorale and the symphony, employs animation and other film elements that bring to life entries from da Vinci’s notebooks. Hagen calls it a Multimedia Symphony.

Hagen’s work was given its world premiere in 2019 by the Metropolitan Symphony Orchestra and Minnesota Chorale to celebrate the 500th anniversary of da Vinci’s death. I saw a film of that performance and was immediately taken with it. Obviously that meant I wanted to talk to Hagen about the work, da Vinci himself and specifically a few things da Vinci said that make their way into her work.

What follows are excerpts from that conversation that have been edited for length and clarity. To see the entire conversation (and there’s much more there than can be put in one print interview), please go to our YouTube channel.

Something that Da Vinci wrote which you know because it’s part of the libretto of your piece is “A painting is a poem seen but not heard. A poem is a painting heard but not seen”. Do we know what Da Vinci’s thoughts were on music?

The only thing that I really remember from my research is that, as you know, not many of his paintings survived. But there is one painting of a musician and some experts believe that is [Franchino] Gaffurio, who is a composer, a contemporary of Da Vinci’s and who I actually quote in the third movement of The Notebooks of Leonardo da Vinci. That was partially the reason why people think that they may have known each other. I think he would have been very interested in the intersection of the art and music, but I don’t remember anything specifically that he said about music.

Over 7,200 pages of his notebooks have survived. What was the process of selecting what most intrigued you and what was going to work best for you musically?

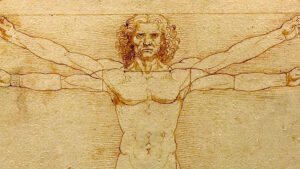

When I write these big, larger works I tend to think of an arc. What story am I telling throughout this entire piece? I knew right away what I wanted for the opening. I knew what I wanted for the ending. Those two things kind of came to me pretty quickly, although for a long time I thought the Vitruvian Man movement might be last. Instead he’s kind of the centerpiece right in the middle of the work.

There were probably four or five different versions of this libretto that I kept whittling down to try and make it a manageable amount of text to set. What ended up making the cut is the text that I not only could tell or had inspiration for what I thought the music was going to sound like, but also I could picture something visually that would go well with it. Those are the things that that won out in the end.

Do you think there’s a poetry to the way he wrote?

Yeah. I think artistic people like him everything they do is art. His handwriting is beautiful. The way he thinks is big ideas and very artistic.

About that writing. da Vinci wrote right to left, which I think is really interesting. That’s the antithesis of how we write today. You start with the visual in the video of writing out exactly as he did. Did that way of writing in any way influence how you wrote the music?

I don’t really think so. I knew the visual of seeing it going across the screen was very interesting to me. The handwriting has its own little loops and this motion which I tried to mimic in the flute. But I think it would have been the same either way the handwriting works. One of my favorite parts about that opening is that it’s the beginning of a creative idea in which he starts and stops and then crosses something out right away. I love that this whole piece starts with a mistake. It’s very human and relatable; oh, yes, he was a person.

Walter Isaacson, who I’m sure you’re familiar with, the author, professor of history at Tulane, said of Da Vinci, “He could not afford to waste paper. So he crammed every inch of his pages with entries that seemed random, but provide intimations of his mental leaps.” There are far more technologically advanced ways of writing music today than there was in the Italian renaissance. But does your compositional process have any similarities to how Da Vinci wrote out of his various ideas?

Yes. In terms of the fact that it’s messy, that two different pieces can share the same manuscript paper. That happens a lot. I also have my own system where I have six different composition notebooks. Instead of having it go from one page to the next they’re all lined up. So if anyone were ever to study my work later they’d have to find all six of them and put them in order. And of course, they don’t make any sense. There’s something really beautiful about the messiness of that. As creative people I think we have to be willing to be messy with it. To cross things out, to scribble, too. Sometimes I draw pictures of what I want texture to look like or even would draw a picture of what I imagined it would look like on the screen. So, yeah, I think it’s relatable.

What inspired you most musically, the drawings or the words?

I think part of the magic is that it all gets thrown in there. One of the ways I love to think about composition is it’s like I’m a witch with a big cauldron and all these things that I love and that influence me get tossed into this big pot. And then I stir it around and then what comes out of it is what’s me, is the confluence of all those different elements and what inspires me that makes it out of there. You never know what those things are going to be until until you’re doing the work.

These notebooks have inspired many other artists before you. For example, Mary Zimmermann created a play based on these same notebooks. Why do you they are so inspirational for creative artists? What is it that he put into these 7200 pages that survive that inspires you as a composer, that inspires her as a playwright, that has inspired countless other people?

I think we’re fascinated and curious about the idea of genius and what it means to be extremely intelligent and diverse in the way that we think about things. If you list all the things that he kind of figured out before everyone else did, it’s an amazing list. In fact, one of the books that I was reading might have been the Walter Isaacson. It had a chart and it said this is when Leonardo thought of this idea and this is when it actually came to fruition. That’s an amazing thing.

I think creative people especially just want to know how he did that. And the truth is that I think throughout his life he remained exceedingly curious. Another thing that I think people love is the fact that he was known as much for his failures as his successes. That’s inspiring, too, to those of us who fail at things before we succeed.

da Vinci contemplated how two paintings have exchanged the senses by which they pierced the intellect. As a composer how do you think this work pierces not the intellect, but the emotion at the core of Da Vinci’s perspective on life?

I think some of my favorite lines are in the ending. “Wisdom is the daughter of experience” and also where knowledge comes from and how it’s based on our own experience. Everything is through that lens; who we are. He saw the importance of the individual and how we see things. Then also how we’re part of something huge and we’re really small.

I love that he refers to the earth as our sun in the last movement, which is also wrong. I love the fact that it was bookended, that he made mistakes at the beginning and the end of this piece.

I think he was deeply philosophical in all of his work and I think that comes across in the piece as well.

In the Italian Renaissance women were at least second-class citizens at best. I love the idea that wisdom is the daughter of experience as opposed to the son. Clearly daughter works better rhythmically for a composer than son because son just lays there as a flat one-syllable word. Have you ever thought about why he chose to make wisdom the daughter? That seems like a radical idea for the time.

I never really thought about it in that way exactly before. I don’t know why. I think he thought very differently from a lot of the people of his time. He must have felt like an outlier. You know that is a really wonderful question that I don’t think I’ve ever been asked before. But as a woman and as someone who’s very much a feminist, I’m sure that’s another reason why I was really drawn to that statement. I always knew that it needed to be the ending.

So it, too, shall be ours.

To see the full interview with composer Jocelyn Hagen, please go here.

Photo: Composer Jocelyn Hagen (Courtesy Pacific Chorale)