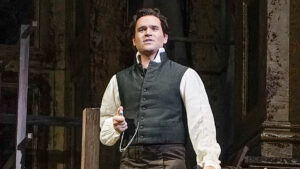

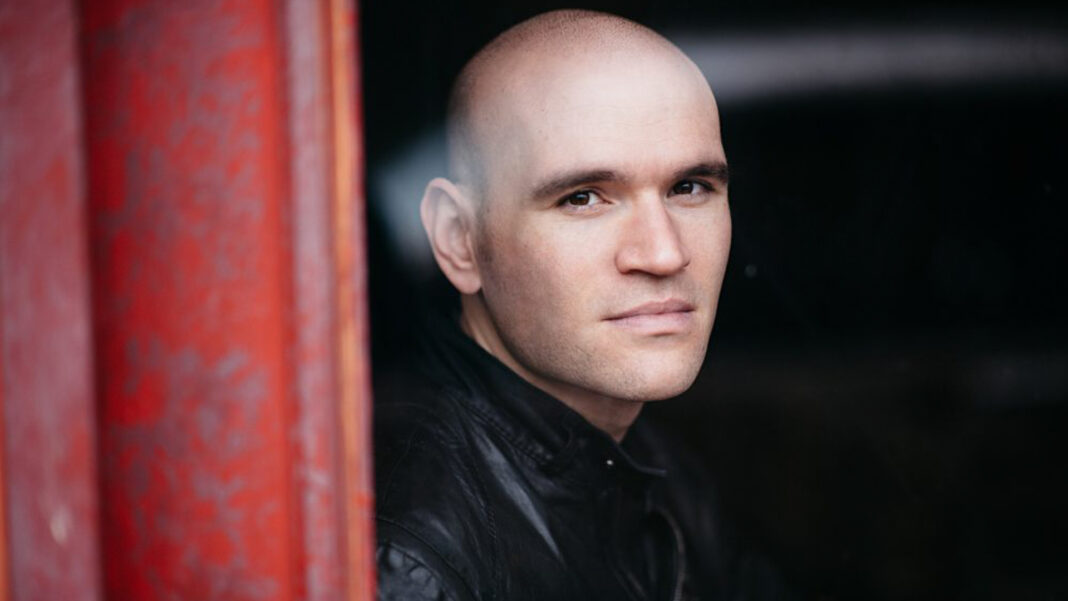

Tonight the Metropolitan Opera will perform Puccini’s Tosca for the 1,000 time. Currently starring in the production – and those who will be on stage for this landmark performance – will be Aleksandra Kurzak as “Tosca,” George Gagnidze as “Scarpia” and Michael Fabiano as the doomed “Cavaradossi.”

Tonight mark’s Fabiano’s last performance in this production. Two weeks later on November 19th he appears in the same part for the first four performances of Tosca at Los Angeles Opera (opposite Angel Blue and Ryan McKinny.)

He and Blue will be performing at The Richard Tucker Foundation Gala in New York City on November 13th.

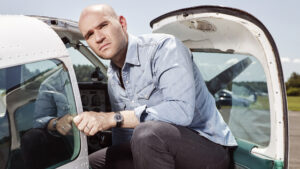

When this highly sought-after tenor isn’t appearing on stage he’s often flying airplanes. Fabiano is actively involved in ArtSmart, the non-profit organization he co-founded with the mission of providing music lessons from professional musicians to students in under-served communities. ArtSmart is holding an auction from November 29th through December 15th which is accessible online.

With two Toscas, a divorce and his passion for arts education, this was good time to talk to the fiercely-intelligent Fabiano about music, his goals for ArtSmart and most of all, healing. What follows are excerpts from our conversation that have been edited for length and clarity.

In 2016 you told Opera News, “I sing because it’s catharsis and I sing because I know that culture is necessary to keep society round.” So rather than focus on exclusively on opera, I’d like to talk about music as a tool for healing. Given everything the world has gone through in the last two-and-a-half plus years, on what level do you think music was part of how society has made it through so far and what role do you think it will play moving forward post-pandemic?

I think that there was at least somewhat of a new awareness of the inherent value in music as a whole and about classical music because people were still inside, they were quarantined. Imagine if music ceased to exist for one day in our lives and in a complete way. No jingles, no news shows, no Spotify, no Apple Music, no nothing. How would individuals feel and what would their response be? My view is that people wouldn’t know what to do with themselves and that’s exactly when they realized the value of music. Suddenly people only had music and drama because that’s all they were locked to.

Music is the most carnal form of communication. When we educate people in a very simple way that music is essential, that it is fundamental to life, that it is aspirational, and that it’s inspirational, we have a really much greater chance at moving the paradigm quickly for culture at large. The reason why I do ArtSmart is because I know that when people are touched by music their propensity to change themselves and change others grows.

When a production of Carmen in which you were appearing in Belgium got canceled, you wrote a public letter. In it you said, “The risk of people not having access to music in their lives is enough to impair mental health and personal discipline.” What challenges did you face when everything was shut down and you were unable to perform?

When a person is not inspired the ability to do other things diminishes. If I’m an opera singer and I live for inspiration through music and suddenly that spigot is turned off, that side of the brain that normally would go into running ArtSmart, co-running a technology company called Resonance, even flying airplanes, my inspiration to do those affairs diminishes.

The reason so many people in the pandemic had difficulty re-upping and getting right back into the swing of work was because they lacked inspiration for so many months. It was difficult for people to just do it on their own in the confines of their own homes.

The double difficulty with that is there are lots of arts institutions around the world that were not doing enough to help artists. So there was this dejected sense from artists that the institutions that employed them were not holding their own obligation. The lack of will to do everything else in daily life, that’s the result when we lose inspiration. It’s not only emotional, it’s scientific.

It’s been 12 years since you first performed at the Met. What does being part of their 1,000th performance of Tosca mean to you personally?

I know, first of all, the responsibility that comes before me as a tenor and the great talents that have sung at the Metropolitan Opera. I know how important this title is and how many different tenors have sung Cavaradossi at the Metropolitan Opera and what personal responsibility not only do I have to the public, but I actually have to the other people that have done justice to this opera. I think I have a idealized ideological responsibility to the other artists, show them that I respect them, their work and their contribution to the field that we so deeply love. As a person I’ve actually sung a lot for Metropolitan Opera. I feel an immense amount of gratitude to be able to step on the stage. And I know that it’s my burden to deliver that.

Is it a burden or is it a responsibility?

I don’t think burden has a negative connotation. Just like what the word consequence doesn’t have to be negative. An added burden is an obligation, a moral responsibility. A burden also means heavy. So it’s a big burden. It’s it’s a meaty burden. I have a moral responsibility to do a good job.

Tosca seems like such catnip for opera lovers. Do you think there’s something about this story that transcends just the music that becomes something that people can attach their own lives to?

The great thing about Tosca is that it’s in real time. Meaning that when the opera begins everything happens to three people in the span of a very limited amount of time. There are no other operas that have that kind of time. It’s extremely applicable today because think about it, our world moves incredibly fast. We get news in the matter of seconds. We find out about that OPEC’s cut output of oil today and there were 10,000 articles written about it in a matter of seconds. That didn’t happen 100 years ago.

Tosca, in comparison to Puccini’s other works, is literally in real time. Angelo escapes. I go to try to hide him. I get arrested in a matter of minutes because, of course, the spies are out there. I’m taken. I’m questioned. I’m tortured and in another two hours or so, I die.

Let’s apply it to real life. This happens today in the Middle East, where people are hunted down for not wearing headscarves the right way in Iran and thrown off buildings. Fascism in oppressive governments throughout the Middle East do this now and run after people and torture them. That’s the scene in this story.

The weird thing about about technology is we learn probably more than we need to know about certain things in the world and not enough about the things we do need to learn about. I say that as a way of mentioning the documentary short film about you, Crescendo, which I think is really beautiful. It concludes with your marriage which did not work out. What role did music play in your healing through that process?

Music has always been integral in my life in all ways. I very rarely have time during the day when music is not either in my head or in my ears in some way. In the period of my divorce and as I was moving into becoming separated and alone again, I oddly started finding Bruckner and Wagner which came to me because I found both composers to have a lot of light and hope inside of music that we don’t always regard as hopeful. I have a new outlook on a lot of that music that I never paid as much attention to.

The result of divorce was learning and paying attention to something else; looking for light in a different way, in a new pathway.

Providing light is something you’re able to do with ArtSmart. What is the biggest accomplishment ArtSmart has made so far?

We’ve dispersed over $2 million in money to working artists. One of the missions of ArtSmart, in addition to serving under-resourced youth, is that we want to compensate working artists as much as possible for their hard work. We partner with working artists to give them an extra bandwidth of income and opportunity. ArtSmart is not a full time job for any teaching artist. I would call a really great side hustle.

I’m proud of that because I remember when I was young, I had debt. I can empathize with artists that are looking for work and need an opportunity. That’s what we do. The joy of the organization is that we’ve been able to disburse so much money to working artists and at the same time changed the course of a lot of kid’s lives.

During the Reagan administration it became verboten to put money into arts programs. Ever since then this country, more than any that I can think of, has de-emphasized arts education in public schools. What do you think has been the biggest cost of that decision?

I’m going to say things that are controversial. You prepared? I don’t think I’m going to say things that are out of line. They’re just not going to be necessarily orthodox.

First of all, I don’t necessarily think government is the greatest arbiter of money for the arts. It’s not to say that they shouldn’t do a better job of how they disburse what resources they have now. But the reality is America is always going to have two parties – hopefully three or four someday. Money is always going to come and go, depending on the financial state of our country. The first thing that is always going to go when cuts happen, is money for culture. That’s just a harsh reality. We have to be a realist about it and not ideological.

So if we know that legislators, regardless of who the hell they are, are going to first cut the tap off for arts funding, we better damn well be self-sufficient as a country and be able to support ourselves. Which is why an organization like ArtSmart should be replicated in many cases.

I would rather create organizations that really can move the dial in schools. Do what El Sistema has done or ArtSmart and other organizations like Sing for Hope. But there is something else. I think there’s a very big difference between arts funding and arts education funding.

At ArtSmart we have spent three years surveying children, teachers and adults to understand the connection between their academic success and studies of musical arts. Does a child do better as a result of their music lesson? We have a lot of causal evidence that demonstrates that when a child or a young adult has a consistent music lesson with a private teacher that their ability to strategize and prioritize and goal-orient themselves improves dramatically for all of their other studies. That’s a case that we could make the Congress.

But it’s not STEM education that’s going to cure lives. It’s STEAM. Education includes arts and it might just be a choir class or an orchestra class. It might be once a week mentoring between an artistic individual and a student for 20 minutes. That’s it. 20 minutes might be enough. Once a week. If we can find that in an artistic vehicle we might be able to create a really large change in the lives of kids.

Leonard Bernstein said, “Music can name the unnamable and communicate the unknowable”. What do you most want to communicate with your music and what does music most passionately communicate to you?

I want to be able to communicate that each person is sovereign. Each person not only is entitled to their own ideas and their opinions, but they’re unique. One thing that we’ve been told in the last 40 years in particular is how we all have to basically be the same. That we have to think the same things, do the same things, be the same thing.

If we use music as a model, composers like Shostakovich, Tchaikovsky, Scriabin, Verdi, we know that these people were sovereign. They had vanguard ideas. They were different. They went in their own direction.

I am not, as an artist, trying to be anyone else. I am Michael Fabiano. I am imperfect. I make mistakes. But I also am proud of the music that I make because it comes from a place of true hard study and deep care for the muse and also deep care for the desire of the public at the same time.

So music, if there’s one thing I want to convey, it should be sovereign and it should be independent and individual.

If we don’t put an emphasis on the individual when it comes to art making, we just end up with generic art. We wouldn’t have Picasso. We wouldn’t have Monet. We wouldn’t have Verdi. We wouldn’t have Shostakovich. If an artist wants a purple room to paint or a singer needs a green room for their dressing room right before they go on stage, you give them the green room because if that enhances their ability to deliver the music that’s delivered to the public, you do it. It’s obliged. Because if we don’t, we run the risk of not getting great experiences for history, for the public and for the public good.

Main Photo: Michael Fabiano (Photo by Jiyang Chen/Courtesy GM Art & Music)

[…] Cultural Attaché […]