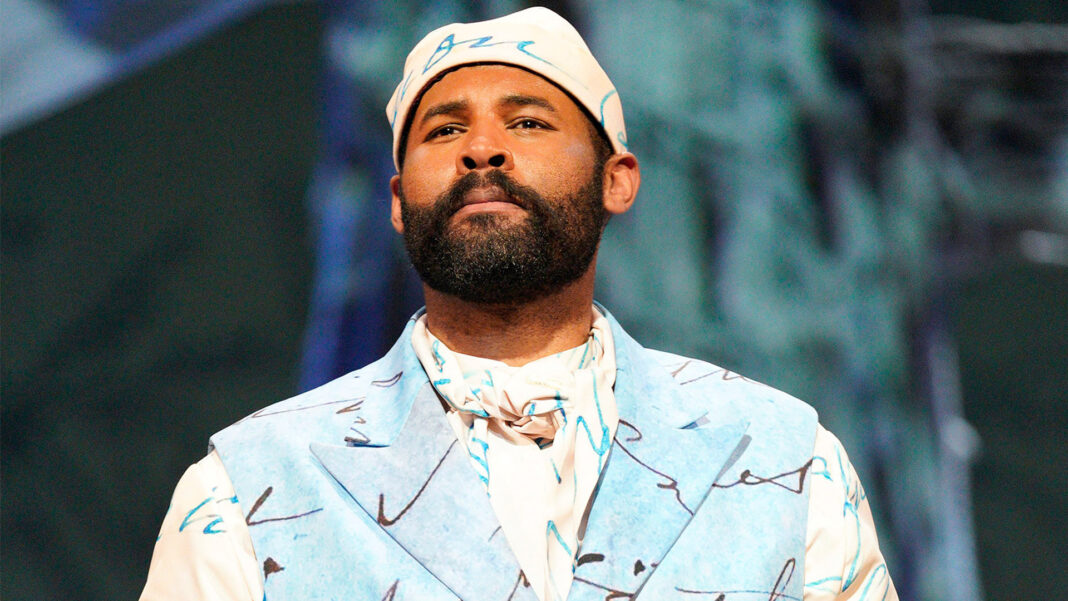

Though Jamez McCorkle had already been making a name for himself in opera, the world premiere of Rhiannon Giddens and Michael Abels’s opera Omar at the Spoleto Festival USA earlier this year elevated his status significantly.

McCorkle sings the title role of Omar Ibn Said, a 37-year-old scholar living in West Africa who was enslaved and sent to Charleston, South Carolina. 24 years later, in 1831, his autobiography was published detailing his life, his experiences and the challenges to his Muslim faith.

The same production is now playing at LA Opera through November 13th. Charles McNulty, writing in the Los Angeles Times, said of his performance, “Even when the libretto feels skeletal, McCorkle supplies an emotional heft. The meditative sincerity of the performance left me with my head bowed.”

It was that inner character and the contemplative nature of the character that I saw on opening night that prompted me to talk to McCorkle. What follows are excerpts from that conversation that have been edited for length and clarity.

On June 6th you posted a photo of yourself as Omar on your Instagram account and said, “I am Omar.” How do you personally relate to Omar Ibn Said?

I’ve come to this story opera through, not necessarily the man, but the representation of the mother in the spiritual form in the opera. She’s basically the one who’s guided his footsteps, telling him that this is the path for you and you should tell your story. She’s looking over him.

My mother passed away right before my college auditions. In my heart I have a connection that way to this opera, feeling as if my mother is also guiding my footsteps in my career. Telling me which path to go. Glad you asked that question because I’ve never talked about it.

How healing has it been for you to be doing this?

I’m glad that when my mother [in the opera] comes, I’m not singing because if she came while I was singing, I don’t know if I would be able to sing very well. But yeah, it’s very special.

How much did you know about Omar before this opera came your way?

Nothing. Most of the people didn’t know anything, honestly. Luckily enough the Spoleto Festival put together a bunch of scholars and got them to do Zoom videos and Zoom calls together to converse about their knowledge. They made it completely open to the public for everybody else to look at.

The fact that they even went that extra mile to do that meant that I had less homework to do and I could focus more on the music itself. I think in a previous interview I said [the music] was easy. I think people misinterpreted what I was saying because it’s obviously not easy to sing, but the way it’s written is very well written for the voice. It’s well thought out for me.

Basically the first act is a gigantic warmup for the second act. My voice has a very large range, but most of the first act sits in more of a baritone range and it’s constantly just churning and churning and trading and warming up and pushing higher and higher and higher until I get to all of my high notes in the second act. It’s just written so very, very well.

You don’t often find somebody who is as contemplative a character in opera as Omar is. What are the challenges in getting out the whys of who he is in a story where he’s not always being very proactive. A lot of what is going on is internalized. How do you approach a character that is frankly, on a lot of levels, the antithesis of what a lot of opera characters are?

For a lot of the role, you’re right. But there are certain moments in the show where you have to wear your heart on on its sleeve. You have to make big differences between these two energies in order to give the character more legs to stand on emotionally.

I myself am very contemplative about everything. I don’t necessarily wear my emotions on my sleeve, but when I’m on stage as an opera singer something just changes and I just become this extremely emotive person. I’m throwing my emotions everywhere all over the stage. So it’s nice to be able to bring these two parts of myself together as one person.

It requires me to acquire more stillness – physically and mentally – and trusting that. It doesn’t always have to be these gigantic gestures. It’s more how you say each and every word, because every word you say now becomes extremely important. The most important thing: it’s not about the colors you can really create with your voice, it’s the colors you can create in the words themselves.

In the score I heard homages to Porgy and Bess, just a little phrase here and there. You appeared in Porgy and Bess at the Met. There are many who call for works like that to be relegated to the dustbin of history because they weren’t written by people who had authentic experiences. What is your view on Porgy and Bess and its place in opera today?

It’s not really my place to say whether an opera should be designated to the trash bin or not. But without Porgy and Bess there would be no Omar. Things go out of vogue, you know? So eventually time will tell whether or not it can stand up to the test of time. But without Porgy and Bess there would be no Malcolm X. There would be no Fire Shut Up in My Bones. There would be none of these new pieces that are being created by composers who are minorities and from a minority’s viewpoint.

Are you optimistic that that that the success of something like Fire Shut Up in My Bones or the success of Omar will inspire other other artists of color to write for opera?

I hope so. Also just to bring to light to the works of all minorities who have written works already that have yet to become mainstream or to be seen by a vast majority of people.

I just went to a the African-American Art Song Alliance Convention at the University of Irvine. I came across works I never knew existed and by composers I had never heard of. I stayed for a couple of recitals and it was just beautiful music. How had I never heard of these people before? So it’s wonderful that we have these giant pillars such as Omar to help unearth the things that are even already there.

On your Facebook account on June 11th you posted, “I get to make music as my career. I mustn’t forget how special that is.” How often do you need to remind yourself how special that is?

I’ve done it my entire life. So it’s almost like drinking water, breathing air for me. It makes it easy to forget that this is special. Not many people get to have this type of experience in life. There’s just this certain aspect of life where if something feels special in that moment, but you have constant access to something that special, over time, it becomes something that you don’t really think about as much as special. What I’m doing in this art form as a classical musician is not something that people get to do very often. And it is very special.

Karl Ernst, a professor of Islamic studies at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill, was interviewed for Religion News in 2020 about Omar Said. He said of his writings, “We have to have a way of understanding how someone like him could have lived the life he did surrounded by people who couldn’t understand him at all.” How has your preparation and performance of Omar allowed you to understand him and how has this project allowed you to understand yourself better?

As an African-American, we tend to walk through life, and it’s been said before, but it’s true, having these two masks. One that we wear around black people and then one that we wear around everyone else. Omar and the way that he would write, it would be as if speaking to two different people at the same time. Leaving hints of Islamic literature inside of his writing that would inform those who are from that path, too. That’s how I come to think of it. It’s trying to walk the line.

I guess it just made me realize that it’s not anything new, you know? It’s something that’s probably going to always be there; having to walk that line. To somehow remain true to yourself, but to still forge ahead and do the things you want to do.

Let’s take this conversation full circle. If your mother could be there to see you perform in this opera and see the relationship that Omar has with his mother, how do you think she’d respond?

Oh, she’d be screaming “That’s my baby! That’s my baby!” She was someone who always fought for me, even when I didn’t really fight for myself sometimes. She always had my back. She was always in my corner. Even if I was wrong. She would love…I’m sure she does love this opera. She’s watching it right now. She’s in love with it. Yeah. She’s smiling for sure.

Main Photo: Jamez McCorkle in Omar (Photo by Cory Weaver)