On November 22nd the Metropolitan Opera will give the world premiere production of The Hours by composer Kevin Puts and librettist Greg Pierce. The production runs through December 15th. The December 10th performance will be screened around the world as part of Met Opera’s Live in HD series.

This interview originally ran in March when the Philadelphia Orchestra was giving a concert performance of The Hours. We have updated this story with more details about the Met Opera production, clips from the production and additional comments from composer Puts. We have also posted the complete interview up on our YouTube channel.

The Met Opera production stars Joyce DiDonato as Virginia Woolf, Renée Fleming as Clarissa Vaughan and Kelli O’Hara as Laura Brown. These were the characters played by Nicole Kidman, Meryl Streep and Julianne Moore in the 2002 film. Both the movie and the opera are based on Michael Cunningham’s 1999 Pulitzer Prize-winning novel.

If you read the book or saw the film you’ll remember The Hours is about three women from different time periods who all have a connection to Virginia Woolf’s novel Mrs. Dalloway.

Also appearing in the opera are Kathleen Kim, Denyce Graves, John Holiday, Sean Panikkar and more. Yannick Nézet-Séguin will conduct all but the last Met Opera performance on December 15th. Kensho Watanabe will conduct that performance. The production is by Phelim McDermott (Akhnaten).

“The idea came to me from Renée Fleming,” says composer Puts. “She was thinking about it and she thought how interesting to have an opera that takes place in three different time periods all at the same time. It was on her mind because she had just had lunch with Julianne Moore..” That’s how The Hours began its life as an opera written by Puts.

Earlier this year I spoke via Zoom with Puts who won the Pulitzer Prize for his first opera, Silent Night. What follows are excerpts from that conversation that have been edited for length and clarity.

Virginia Woolf once asked, “Why are women so much more interesting to men than men are to women?” Your opera of The Hours is based on a novel written by a man who was inspired by Woolf and is being created and directed by three men. What would you say to Woolf if given the opportunity to address her question?

I can’t answer why, but I would say for me women are more interesting as characters. I don’t know why. I love operas like Billy Budd, but these characters are fascinating and I like writing for the female voice very much.

Just before speaking with you I had the television on and I was flipping channels around and the movie Aliens was on. It’s the same thing, [director] James Cameron is fascinated with female heroines in his story. I don’t know exactly why.

My first opera was basically almost all men and now I’m starting to get my musical mind around having melodies that are essentially around middle “c” on the piano. That is a different kind of thing because then the harmony has to be in a different place, et cetera. I don’t like to get too technical, but it’s very natural for me to write for women’s voices. But that is a very Virginia Woolf thing to say and probably true as well.

You mentioned that, like the novel, your opera takes place in three different time periods. Musically how are those time periods reflected and is that necessary for an audience to stay on course with the story you are telling?

The piece has a very kind of otherworldly and kind of mystical feel to it. But definitely we want the audience to know what’s going on.

I didn’t have a real premeditated idea that there would be three different types of music, which would be extremely different and would signify the different characters. But I think it just happened naturally.

Virginia Woolf feels trapped in Richmond and she wants the wildness of the city. So there’ s a musical language and certain elements of that language which describe that for me. Then there’s her sort of manic desire for London. So there’s that kind of dichotomy in her music.

Laura Brown, the middle period character, was living outside of Los Angeles after World War II. WIth her husband and her three-year-old son, she feels trapped in sort of an alien domestic world that is not natural for her. So there’s a way of describing the world that she can’t fit into, which has its own language.

Clarissa, Renée Fleming’s character, has a kind of musical language that is characterized by Clarissa’s eternal optimism and radiance. She thinks everything will be fine if we just have the perfect party and we get the flowers exactly right.

I really do think of them as musical environments. They’re not leitmotifs, but they’re languages that I think are associated with the different characters and their situations.

This opera has been in the works for quite some time with Fleming, O’Hara and DiDonato attached. Did that allow you to write specifically for their voices?

It was very much written for the three of them because we hadn’t started writing yet. So I knew who we were writing for. I knew Renee’s voice very well having done a couple of projects with her. And I knew Kelli O’Hara’s voice from musical theater. I was talking to her a lot and finding out that she actually has an incredible range and she can sing the lyric soprano roles. And, of course, I knew Joyce DiDonato’s voice. The piece will continue to be written for the three of them over the next several months.

I really think that’s crucial for an opera to make sure that the principles really feel like they can deliver with their parts. It’s funny how minute the changes can be and sometimes that makes a big difference to them. It’s easy for me and actually really satisfying for me to develop these roles within the parts of their voice that work given the situation.

How did Greg Pierce become the writer you wanted to adapt Cunningham’s novel and create the libretto?

Greg had only done one opera, Fellow Travelers, which is a really successful opera with Gregory Spears. I read the libretto and I really liked it. I also liked the fact that he hadn’t done a lot of operas. He had done work in other areas: screenplays, et cetera. He showed me some poems that he wrote. I knew there would be a poetic element to the language. It’s what inspires me. I think that there has to be some poetry in the libretto. His enthusiasm for The Hours was clear. He had been thinking about it for years as a possibility as an opera. In our first conversation I felt like we were already writing it. It just felt natural once I met him.

In the spring of 2021 you had a workshop of the music with Cincinnati Opera. What did you and Greg learn from that session and how did it inform the subsequent work you’ve done on The Hours?

My score was marked in red. I just went to work immediately. Once you figure out what you need to do you just want to forget the past like it never happened.

I think that one of the really crucial scenes in the opera was entirely re-written. It’s a complicated scene actually. A couple of scenes between Clarissa and Richard. I need to work really hard at dialogue. I feel like it should all feel like part of a seamless musical flow and there should be real singing in the dialogue. It should flow naturally like a conversation that kind of ebbs and flows. So those scenes, in some ways, require the most work.

How did that work in the middle of the pandemic?

That was a heroic thing that they did. We were all in a massive ballroom and there were twelve singers – all of the masked in little separate booths with microphones. The pianist and the conductor were in the middle of the room and none of us could approach each other. But we got through the entire opera and we learned a ton from it.

Given that Mrs. Dalloway is so revered, as is the language of Virginia Woolf and that The Hours is revered both as a book and a movie for the language that Cunningham and screenwriter David Hare used, what challenges do you face in continuing with a successful telling of this story?

I think it always is the case when you’re working with a property that’s really known. It’s inevitable. They’re going to be reactions like “well, it’s not like this. And I love the book and it’s too bad that it’s not this way and that way.” It was certainly true of The Manchurian Candidate, my second opera. It was the same kind of challenge.

But I felt like when I began composing that I was doing things on my own terms. It just feels different – just the nature of the piece. I feel like it’s its own thing and it’s not going to feel like the book. It’s not going to feel like the film. The music has its own personality, I hope. But yeah, that’s definitely a challenge. I hope that people will listen to it on its own terms.

The nice thing is the book and the film will still exist independent of the opera.

As soon as Renée mentioned the book I started thinking about the possibilities that can happen on an opera stage that cannot happen in a film. You can’t split the screen in three ways. These stories can begin to intermingle and overlap and they can sing duets that transcend time. That was what was really exciting about it for me because with the language of music and harmony it’s possible to do that. So that’s why I wanted to do it.

I think about that all the time. What’s the point? But I think with this I really thought there was a point.

Michael Cunningham said in an interview when the novel was released that he felt that he entered into some kind of maturity with The Hours and that it was something only he could have written. I’m wondering if you could compare your own thoughts about your perspective of having written this opera at this point in your life and whether you’ve reached a certain kind of maturity and if only you could have written this.

I don’t feel that I’m the only composer who could have written this. But I do think that the way I like to approach opera is well suited to this story. The emotional situations; I live for these these things as a composer. I live for the moments when I can let these situations wash over me and let music come out. This is why I do it.

I think as far as maturity, I feel like now I understand how to not only how to write for voice and how to set the English language and the way I want to that really extracts all the musicality that’s possible out of it. i really love to set English as a language. But also I feel like I’ve kind of tempered my, what is often described in Silent Night, as a kind of a poly-stylistic approach. I’ve tempered that in a way that feels like it’s more cohesive and more kind of all me, even though there are references to different stylistic things that occur in the piece. So yeah, I feel like it was a good time for me to write this opera.

To see the full conversation with Kevin Puts, please go here.

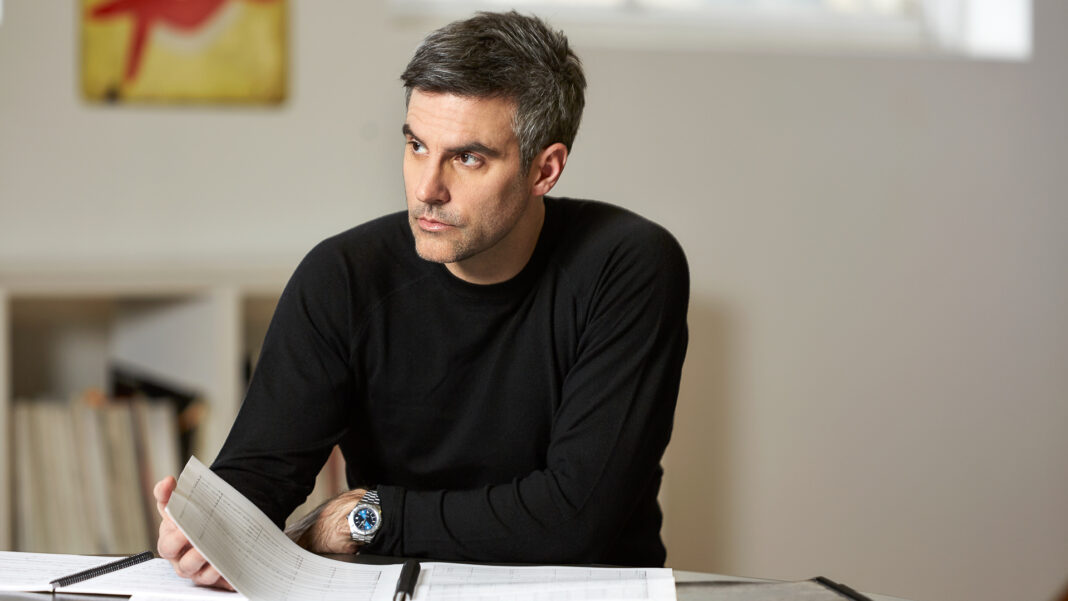

Main Photo: Composer Kevin Puts (Photo by David White)