There are numerous pieces of the classical music repertoire that are always played around the world at this time of year. Handel’s Messiah and Tchaikovsky’s The Nutcracker certainly head that list. If conductor and pianist Christian Reif has influence on what gets added to that list he would add John Adams’ El Niño.

Reif, along with soprano Julia Bullock (the couple are together), have conceived of a one-hour version entitled El Niño: Nativity Reconsidered that will be performed on Wednesday by the America Modern Opera Company. This is his effort to make this nearly two-hour Nativity Oratorio from 1999 more accessible for a wide range of performing arts organizations and audiences alike. The performance will take place at the Cathedral of Saint John the Divine in New York.

Their revision was first performed in 2018 at The Cloisters in New York. As with that performance, Bullock will be joined by countertenor Anthony Roth Costanzo and baritone Davóne Tines. Mezzo-soprano Rachael Wilson sings the role at this week’s performance that was previously sung by J’Nai Bridges.

Earlier this month I spoke with Reif about El Niño, how Bullock’s relationship with Adams made this project possible and about the miracle of birth. He and Bullock recently had their first child. What follows are excerpts from that conversation that have been edited for length and clarity. To see the full interview, please go to our YouTube channel.

The year that El Niño premiere, John Adams gave an interview specifically about this work in which he said, “I want the work to be flexible and not tied to any one way of presenting it.” What were the conversations that you and Julia had when you came up with this revised version of presenting El Niño?

Julia and I love the piece so much. It’s one of the great pieces of our times and it has this immediacy and this intensity. We wanted to focus on that intimacy and immediacy of the work which is reflected both in the subject matter, but also how we have decided to perform it. It’s so hard to cut anything of John’s music and the poetry, but we tried to focus on the relationship – the bond between mother and child.

It basically started with us believing that this piece needs to be heard by more people and be performed by more people. The original, which is so impactful and wonderful, is a big, big piece. It has a six soloists, three of them countertenors, a big orchestra, a big chorus and children. Not every ensemble, not every orchestra, not every chamber orchestra has the resources to perform it. John gave us the blessing for it.

I can’t imagine too many composers being open to having their works altered by other people.

I don’t know if this is just speculation, but if it was anyone else other than Julia Bullock asking John Adams, since they have such a wonderful close relationship, I’m not sure he would have been quite as happy or forthcoming. Julia approached him for her Met Museum residency and he was supportive of it. That was one iteration of it, but we there were several parameters during this presentation.

We played it at The Cloisters so it had to be a certain amount of people only. Also the length was an hour. So there were several restrictions that we wanted to break out a bit now for this iteration. I did a lot of arranging of it for the first one, but I didn’t start from scratch at that point. There was someone else. Now that we’re performing at the Cathedral of Saint John the Divine on December 21st, that is my arrangement and Julia’s concept.

For people who saw it at the Cloisters in 2018 what’s going to be fundamentally different about what’s getting performed this year?

It’s not fundamentally different. We have a 10-piece chamber choir which is one of the major changes. Also the instrumentation is different than we played it at The Cloisters. I added both the clarinet and the horn back into it. I went closer to John’s music, especially in El Niño, but also in The Gospel According to the Other Mary. In these two oratorios much the heart of the sound are the keyboards: it is piano, it’s sampler synthesizer and also harp guitar. Those are the heart of it.

In that same interview that I referenced at the beginning of our conversation John Adams said, “The piece is my way of trying to understand what is meant by a miracle.” How do you understand what is meant by a miracle?

That’s a big question and I’m hoping I can answer it somewhat. John is a father and grandfather and now our son was born six weeks ago. That miracle, I think maybe that’s stereotypical or cheesy, but it is a miracle witnessing birth. Of course we know what is going on in the body and how it’s all happening. Julia and I researched a lot. But there’s something special having this miracle of birth and being so close to it. Obviously I didn’t give birth myself, but I was there every step of the way and that is a very special feeling. So I can only imagine that John was thinking a lot about his own family.

What is so fascinating to me is the selection of poems and poets that John and Peter Sellars collected for El Niño. It’s not, as usually is the case with a lot of Western European music, the birth is not presented through the lens of white men. Rosario Castellanos, an incredible poet, is featured very prominently in both the original and El Niño in our arrangement. It’s very important to us as well. It’s an incredible honor and privilege to raise a child. And I think that miracle is being brought through and shines through the whole piece.

Do you feel like the piece is going to resonate differently with both of you now as a result of having given birth to a son?

I think so, yes. Even just in these last few weeks, when I read the poetry and studied the music, it hits differently. It always impacted both of us in a very deep way. There’s something inexplicable when you read the beginning that talks about how this other being takes some room in the woman and suddenly your body is not your own anymore. You’re nurturing another human being. This is the only time you’ve been alone. Now you will never be alone anymore. That’s something that you grasp when you have given birth or as the father, the partner being right there. I think that’s something I wouldn’t have thought about too closely before.

Does the success of this version of John Adams’s work make an argument for truncation of larger works in a society that demands shorter pieces because of shortened attention spans?

I think being able to experience this work – it is only an hour long. I think it’s not too much task for anyone. If it was a Wagner opera of four or five hours, I understand that’s a daunting thought. But I think to sit one hour and experience a work like this and being able to really delve into it and let everything else go is good.

I think our generation right now wants that, too. They want to be able to let go as well as being impacted deeply. They want an experience. This is some of the most ferocious, most incredible and intense music and lyrics. At the same time, some of the most delicate and wondrous. So I think that is something that would speak to anyone.

And I know from many conversations with my family who have seen this or experienced the full original version, who might not be necessarily the most adventurous contemporary listeners, but were deeply impacted and and taken by this piece. I think this is a piece that people will be drawn to.

You serve as conductor and pianist on Julia’s album, Walking in the Dark. It should be noted that Memorial de Tlateloloco from El Niño is one of the pieces you recorded for the album. What were the conversations that you and Julia had that led to works that were selected?

It’s her album, but obviously since I’m conducting and also playing piano and her partner in life, we exchanged a lot of ideas and thoughts. I think it started with her conversation with Bob Hurwitz from Nonesuch Records who told her, “Don’t worry about what sells. Don’t worry if you can tour the album. Think about the time you live in right now. Think of what speaks to you the most. What do you want to say? The album should be a work of art.”

That really spoke to her. That speaks to me. She has an incredible gift for curation and that comes through in everything she does. She went through many different versions of different ideas of the album; what it might be, what it possibly could be. She asked me for my input with it. She started with talking and working on [Samuel] Barber and John Adams. We were traveling together performing Barber’s Knoxville: Summer of 1915. Since we just are performing Barber, I thought, why don’t you think about anchoring the album with two bigger orchestral pieces.

I’m going to go one more time back to that John Adams interview from 2000, because I found it really intriguing. He said, “Entering into this myth, making art about it and finding your own voice to express it, can’t help but put you in a very humble position.” At this point in your career, whether it’s El Niño or Walking in the Dark, how does your work put you in a humble place and what realizations do you have as a result of that?

The act of conducting, being in connection with each other and with the musicians on stage, is very humbling. I never saw myself as the dictator on the podium. Sometimes I just listen and see what is being offered and make music in real time. It is a very humbling experience. The main thing as a conductor is just to bring everyone together and make sure that everyone can perform on the best level possible. And if you’re not humble in that, I don’t think you get that response from people.

As a father of a young boy, it’s humbling in a different way where I feel my whole being is in service to this young being. Everything else is taking a little bit of a backseat. At the same time I know when I’m on stage I am onstage fully present. There’s also nothing like it.

I did one gig in Colorado a few weeks ago. A sister was able to be here and help out, which was wonderful. I missed Lucas and Julia tremendously, but I was also able to just be with the musicians and be completely present and connect with them. That is a very humbling and very wonderful experience.

To see the full interview with Christian Reif, please go here.

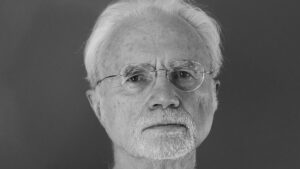

Main photo: Christian Reif (Photo ©Simon Pauly/Courtesy ChristianReif.eu)