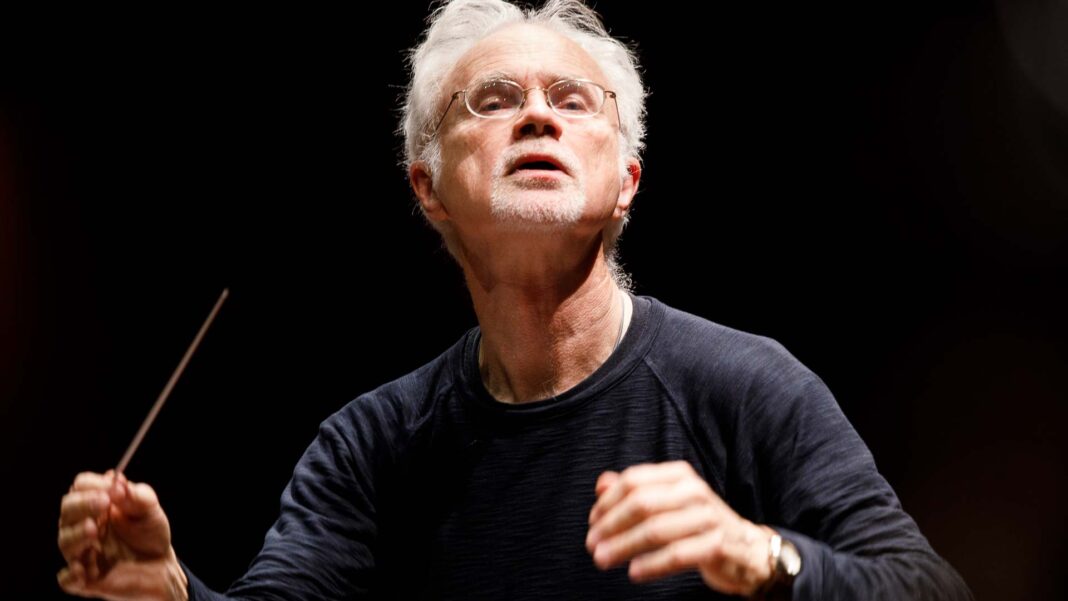

“I couldn’t imagine being just a composer and letting somebody else perform and never, ever being a performer myself. I love the thrill of walking on stage now and sort of getting nervous. It’s really wonderful.” That’s how composer (and obviously conductor) John Adams describes his ongoing relationship with his music.

It’s a relationship that he’s been cultivating for decades. Adams is a Pulitzer Prize winner (On the Transmigration of Souls), an Erasmus Prize winner and the recipient of five Grammy Awards.

For over a dozen years he’s held the position of Creative Chair with the Los Angeles Philharmonic.

This weekend Adams will conduct the LA Phil in a concert version of his 2017 opera Girls of the Golden West. He collaborated with Peter Sellars on this opera that is set during the Gold Rush in California in the 1850s. Most of the cast that appeared in the opera’s world premiere at San Francisco Opera are returning for these two concerts. This includes Paul Appleby, Julia Bullock, Hye Jung Lee, Elliot Madore, Ryan McKinny and Davóne Tines.

Last week I spoke by phone with Adams about the opera, his career and the future of classical music. What follows are excerpts from our conversation that have been edited for length and clarity.

This area of California where the gold rush was centered was an area that resonated with you as soon as you came to California. How has your relationship with that area of the state where you live and its history evolved over that time?

I’m an immigrant. Like all the people came out here looking for gold in the 1850s. I came out here in 1971. I suppose California was a sort of dream at the end of the rainbow for me. I was born in New England and actually had never been anywhere else. I didn’t expect to stay here, but I never went back. Not too long after I arrived I started going up to the Sierras and I eventually bought a cabin up there at about 6700 feet. So it’s pretty high up. I have a very deep feeling for the land.

I did not know a lot about the gold rush history until I started researching for this opera and these stories really became intensely important to me. Making this particular piece was very special. In some ways it’s the most personal piece of mine because of that resonance with the land and with the history.

After the premiere in San Francisco you reworked the opera and made some cuts. How much does this revised version, which I assume is the version that’s being performed at Walt Disney Concert Hall, reflect a clarification of what you wanted to accomplish?

Well, it’s actually the third version of it. This particular version I had to prepare because I have this extraordinary opportunity to record it with the Los Angeles Philharmonic. And I can tell you for any composer alive to get the chance to get a good recording of an opera is extremely rare and I’m just very fortunate. But all of my operas have been recorded.

We had to squeeze it into a regular subscription week, which is very limited rehearsal time and the orchestra obviously has not seen it before. So I did have to make a compressed version of it. But I like this version because it’s focused very, very intensely on the narratives of the characters. The original version had a lot of songs, a lot of entertainment. Things that I’m sort of sorry to go, but really weren’t entirely germane to the story. It was really long.

I had no idea I’d written so much music. It was 600 pages of score. Even when it was revised for Amsterdam, it was still too long. Particularly my musical language, which is sort of wry and tight and economical – the way you might pack a backpack to go hiking in the Sierras. I really felt that this story needed to be told in a more compact, shorter version.

I would assume that even squeezing in these performances as part of the season, it must be a blessing to have all but one of your original cast members back.

Of course. I don’t want to use the word squeezing it in. The Philharmonic has given me as much time as they can. I would say that of all the orchestras in the world, and I have conducted most of them, the LA Phil was the ideal orchestra for this because they have one of the fastest learning curves of any group of musicians in the world. And they know my music. They play it every year and I’ve been conducting them since the 1980s – back when they were at the Music Center. So this is the ideal situation if I’m going to work with an orchestra.

Grant Gershon conducted the premiere in San Francisco. How do you think your approach to this opera, from the conductor’s point of view, will differ from his? In what areas might it be the same?

You know, it’s not like [German conductor Wilhelm] Furtwängler versus [Italian conductor Arturo] Toscanini or something like that. Obviously when Grant conducted that he had singers on the stage and they were doing all kinds of physical activity. And they were singing off book, which puts such a huge responsibility on the conductor. Here I’ve asked the singers to use music because we just want to get it as good as it can. Obviously this is a concert performance with no action on stage. My goal is to just get as good a performance and tight of performance as much as possible.

But do you feel that you conduct your music differently than others do?

Well, sure. I’m very, very lucky. I’ve had the best conductors on the planet doing my music. That’s a real luxury. But I stay in touch with all my pieces. I conduct them regularly and I think I’m a good conductor – at least for my own music. I work regularly with the best orchestras in the world. That’s a plus that most composers can’t do.

You know I saw Aaron Copland conduct when I was a kid. The Boston Symphony loved him, but he was barely able to conduct. It’s a rare group of people who can conduct and compose: [Leonard] Bernstein and [Pierre] Boulez and Esa-Pekka [Salonen]. But most composers just don’t have the experience.

By having that continued relationship with the vast number of your works that you conduct, how does that fuel your ideas for what you want to do moving forward?

Of course it does fuel it. When I do my pieces I really understand what is right about them and what’s not right. So I’ve had the benefit of doing various pieces many, many times. It’s interesting because I was having to make some programs this week for various orchestras because they’re all ready to announce their seasons. I was looking at scores of [composer] Charles Ives that in the past I’ve conducted. I think Ives, whom I love on a certain level as a wonderful human being and a kind of visionary, but there’s something very unsatisfying about most of his orchestral pieces. The reason is that he never heard them played. So they were all kind of speculative. Then you look at a composer like Ravel or Mahler or Richard Strauss who are just constantly sharing their pieces and refining them. The ideal is to have a hands-on experience with your work.

You and Peter Sellers did an interview at Guggenheim Works in Progress in September of 2017. He described the music that you wrote for Scene five of Act two as of Girls of the Golden West as being able to perfectly give voice to what was happening at the time and that historians will be able to look back at that music and see that you had “actually touched what’s going on.” When art and current events collide in the way that he’s describing, is there a part of it that feels like it’s perfect planning or is it the world working in mysterious ways? How do you view that kind of synchronicity?

I think I’m more modest in my expectations. I mean, it really sounds great, very grandiose what he said. But I’m always a little skeptical of language like that. I think basically people have very intimate experiences with a work of art. They may be sitting in a big crowd with thousands of people. But how you respond to something is a very intimate experience. I don’t think you can really predict how people are going to react.

Even though a lot of my pieces deal with historical events, when I’m composing I never feel that I’m preaching to people. I never want to preach or think that I’m going to grab them by the lapel and give them a lecture.

You’re also heavily involved with L.A. Philharmonic’s New Music Group. You have a concert coming up with them in March. What gives you the most optimism about the contemporary classical music that we’re going to discover in the next few years? Do you think that there are composers who are on the cusp of having a breakthrough the way you did with Phrygian Gates?

I think it’s always been the case that there’s never been more than a handful of truly great composers at any particular time. If you look at the era of Beethoven there were all the other composers, his contemporaries, but we only listen to them out of historical curiosity. There was a period around the turn of the 20th century when there were an amazing number of really great composers all alive and working: Debussy, Stravinsky, Mahler, Strauss and Sibelius. But that was rare.

With that said, I think that this is a much healthier time to be a composer than when I was in my 20s or 30s. Back then that was what I call the bad old days of extremely obscure approaches to composition. Whether it was serialism or chance music, various systems that created a kind of music that was absolutely inaccessible to most listeners. I have no idea why it became so prestigious. But it did. When I was in college in the late sixties, early seventies, that’s the music that was treated seriously. And of course, one of the things that did was it frightened audiences away.

Even to this day I still suffer from that. If a piece of mine is on the program and your average concertgoer doesn’t know who John Adams is and looks at the program and sees Beethoven, Mendelssohn and Adams, the first thing they think is that it’s a new piece. It’s going to be unpleasant. That’s the long tail off of what happened back in the sixties and seventies. Now composers are not driven by style and they are very conscious about whom they’re writing for and what they’re writing about.

I think there’s a lot of interest in encouraging young composers. Virtually every orchestra program I see these days, at least by American orchestras, has a piece by an emerging composer. It’s astonishing because you never saw that 50 years ago or even 30 years ago. So there is interest, but the issue is writing a piece that’s going to have legs that people want to hear. That other orchestras and performers and pianists want to share. That’s really where the dividing line is, because there are very, very few pieces that have legs.

Do you think that that the world is is catching up to what you have been doing throughout your career?

Well, you know, I’m like any contemporary composer except maybe John Williams. I have a modest audience and I say modest compared to a pop musician. But I have what I think is a quality audience who appreciates deeply what I do and loves my work. The reason we call it classical is because we always feel what we’re doing is going to have a very long shelf life, hundreds of years. We’re making something that is not just for now, but for many, many generations ahead.

Bachtrack had you as number three on the top ten contemporary composers whose works were performed last year. [Arvo Pärt and John Williams were in the first and second position.]

I guess maybe it’s just because I’m a Yankee at heart. I’m just very skeptical of grandiose language and things like that. But maybe that’s healthy because I still keep doing very original things. You know, I came back to this opera, The Girls of the Golden West, thinking it had been a failure. I hadn’t even listened to it or looked at the score in five years. [When I did] I thought, not bad.

Main Photo: John Adams (Photo ©Riccardo Musacchio/Courtesy John Adams)