A lot has been written about our lives today in the post-George Floyd era. For tenor Lawrence Brownlee, who made his Metropolitan Opera debut as Count Almaviva in Rossini’s Il Barbiere de Siviglia in 2007, not enough attention has been given to the triumphs of the African-American population in the United States.

So he set about creating a recording and concert called Rising that celebrates those triumphs through the work of poets from the Harlem Renaissance. Amongst the poets whose works have been set to music are Arna Wendell Bontemps, Joseph Seamon Cotter, Jr., Countee Cullen, Paul Laurence Dunbar, Georgia Douglas Johnson, James Weldon Johnson, Langston Hughes and Claude McKay.

Many of the works were newly commissioned by Brownlee for Rising. These include compositions from Jasmine Barnes, Shawn E. Okpebholo, Damien Sneed, Brandon Spencer and Joel Thompson. There are also compositions previously written by Margaret Bonds, Jeremiah Evans and Robert Owen.

On Thursday, March 23rd, he will perform Rising at Carnegie Hall in New York with pianist Kevin J. Miller who also appears on the album. That will be followed by appearances at the Kennedy Center on March 26th, the Kimmel Center in Philadelphia on March 29th, Ithaca College on April 1st and Ball State University in Muncie, Indiana on April 4th. The album will be released in June.

Earlier this month I spoke with Brownlee about Rising, the Harlem Renaissance and the poets chosen for the project. What follows are excerpts from our conversation that have been edited for length and clarity. To see the full interview, please go to our YouTube channel.

Writer, poet and activist Zora Neale Hurston, who established the Harlem Renaissance movement, said, “There are years that ask questions and years that answer.” Having commissioned Cycles of My Being, a song cycle about life as an African-American living in America by Tyshawn Sorey and Terrance Hayes in 2018 and now multiple composers for Rising, how would Hurston’s perspective apply to the time between these two projects and their relationship to one another?

I believe as an artist that I’ve matured. I feel like I have a little bit more understanding what I want to say, what I feel like my audience is and my ability to get people interested using the writings of others. James Earl Jones talked about having a terrible stuttering problem and he had a theater teacher who told him that he could use the work of others to really be meaningful in his own work.

So I take the same thing and the work of Zora Neale Hurston, Langston Hughes, Jessie Redmond Fauset, Countee Cullen, Claude McKay and so many other people of the Harlem Renaissance that inspired us. A lot of people know about Langston Hughes and W.E.B. Du Bois, but they don’t know about James Weldon Johnson and some of the other people. What Zora Neale Hurston said, I think, is true. Time does focus you a bit. It gives you more insight. It gives you more perspective.

In the liner notes you say you wanted to create something that speaks “not just to our struggles but to our triumphs.” Has the attention, which is long overdue to the struggles, particularly post-George Floyd, meant that the triumphs have taken a backseat in both the national consciousness and in the conversation we’re having?

I think so. A lot of people focus on our struggles and they focus on the pain. These things are ubiquitous. They’re everywhere. They’re constant. People know about the suffering.

I specifically talked to these composers and said I want you all to choose your own text. We presented them with the texts. But I told them that I want them to focus, if they want to, on the joys, the passions, the triumphs. We love love. We love moving ahead in society. We love the positivity.

That’s what I wanted to show. I want to talk about the triumph, the joy, the relationships. That was really important in Rising.

Of the 29 selections that are on Rising, some of the compositions clearly predate the project. What was the process of selecting the other poems to be set to music and the composers who would write that music?

The thing I think Rising shows is that the wealth of the different voices and the different approaches in composition and their different influences. You could see some people were greatly influenced by jazz, some by gospel, some by a wide array of things, some by classical, some by Stravinsky. There’s a wealth of different styles and different voices that I hope people appreciate in this project.

There was one decision in the liner notes that I thought was particularly intriguing. You do not put any information as to who wrote which poems in the liner notes. After listening to it the first time, some of them I knew, but I spent the next 40 minutes looking them up to see who had written these poems. I assume you are trying to inspire people to be participants in this project?

Absolutely. I wanted people to go into search because if you put in Google “writers of the Harlem Renaissance,” there are not three. There are tons of them. People didn’t know who Arna Bontemps was. People didn’t know who some of these writers who have made such amazing contributions to to the canon of writing. I want people to go in that rabbit hole and to search. I’m thankful that I can be a part of the exploration. I hope people will take a really deep dive.

Amongst all the writers whose poetry is included in this album, it is no surprise that Langston Hughes is the predominant voice. What makes his poetry so appealing for a composer since countless composers have previously set his words to music?

I think it’s accessible. I think there are some people who have a real gift. They are prolific in the writing. They can write on a number of different subjects. Langston Hughes is someone who’s been able to show that and demonstrated that – even with the six composers that we worked with on the album. Many of them focused on Langston Hughes. Not because it was easy, but because it inspired them.

Many of these composers that wrote for Rising, but also the ones before predating the project – and there are so many others that wrote with the words of Langston Hughes – did so because it was meaningful to them. They felt that they could say something with their own artistic voice using his work.

What are you able to say with your own artistic voice when you get to sing lines like “A lady named Day fainted away in the dark,” from Night Song which I think is spectacular. Or “In silence every tone I seek is heard” from Hughes’s Silence?

[Composer] Robert Owens. I fell in love with his writing. Some of his songs are about 30 seconds, but they’re impactful. It gives me an opportunity to explore, to be expressive. Performing this recital that is all in English – as someone who does a lot of recitals that are different languages – and even in the different languages, I like to explore expressivity and to really be meaningful. But the weight of the word, how it falls on a language that is your own, it’s different.

“The lady named Day fainted away in the dark.” The setup for that has to be right so people feel the gravity of the situation. Using every tool that you can from a descriptive standpoint, but also a musical and artistic standpoint. I try to focus on the text and to couple it with what I’m given from the poet and the composer and my voice all come together, hopefully to create a special moment.

Langston Hughes knew there was a musicality to his his writing, didn’t he?

Well, I think they all did. You have these people who being in the hot spotlight of New York. Could you imagine? The great jazzers, they were all there. Some of the great songstresses they were all there. New York was a hotbed. The great Sidney Poitier moved from Nassau, Bahamas, to be in New York City. He was a dishwasher before he became the great actor that he was. It was because he saw a movie with a cowboy on it and he wanted to be an actor. He came where? To New York.

The great Charlie Parker was in New York. The great Miles Davis was in New York. All these wonderful writers of the Harlem Renaissance. I’m sure that there was some cross-pollination and inspiration amongst themselves that maybe was even inspired by music they couldn’t get out of their head that Miles Davis played or the great Dizzy Gillespie played. It inspired their own creativity.

Do you think it’s possible to have another era like that?

Oh, I hope. I think it’s important for people of this time, like myself and others, to record. I think it’s something that we have to say. We want to contribute to the whole history of life and how it progresses even beyond 2000s into the 3000s. We can’t even think of that because I won’t be here in however many years from now. But I think people of this time have something to say about all the outside factors that affect who we are as people and artists. I think that will be important for people in the future. So much of what I’ve learned from these writers, from these musicians of the past, makes me the artist that I am today.

Langston Hughes was asked about the purpose of art and his response was “Perhaps the mission of an artist is to interpret beauty to people, the beauty within themselves.” How does Rising allow you to interpret the beauty within yourself and by extension, share that with your audience?

I like to think of myself as a vessel. But in being a vessel, I think people look at you and will make assertations about you. People will maybe size you up and try to imagine what it is that drives you. Being an expressive artist is sometimes about challenging my own self. What more can I do? What are the special moments that I can create? For me there is never a quantifiable perfect recital. I don’t think you can quantify what perfection is. But I think it is important as an artist to try and create special moments. The way that I can do that is with thought and intelligence.

I tell the students all time to make sure that you don’t ruin the payoff. Some of that is leading them to the water so they drink. But the time that they drink is by design. We can’t give them the payoff. That will be far more effective if it’s in the right place. So how do I do that? I do that with musicality, with intention, making sure the high point of whatever specific song is at a certain place.

That takes a lot of thinking. It’s not me just getting on stage singing the right notes and rhythms in the right times. It’s so much more than that. Someone told me the last thing you do is sing and all of the work comes beforehand. Getting that in line and having thought that out and gone through that, having performed it already, I feel now that I have a really good grip on what I want to say and being a more expressive artist.

To watch the full interview with Lawrence Brownlee, please go here.

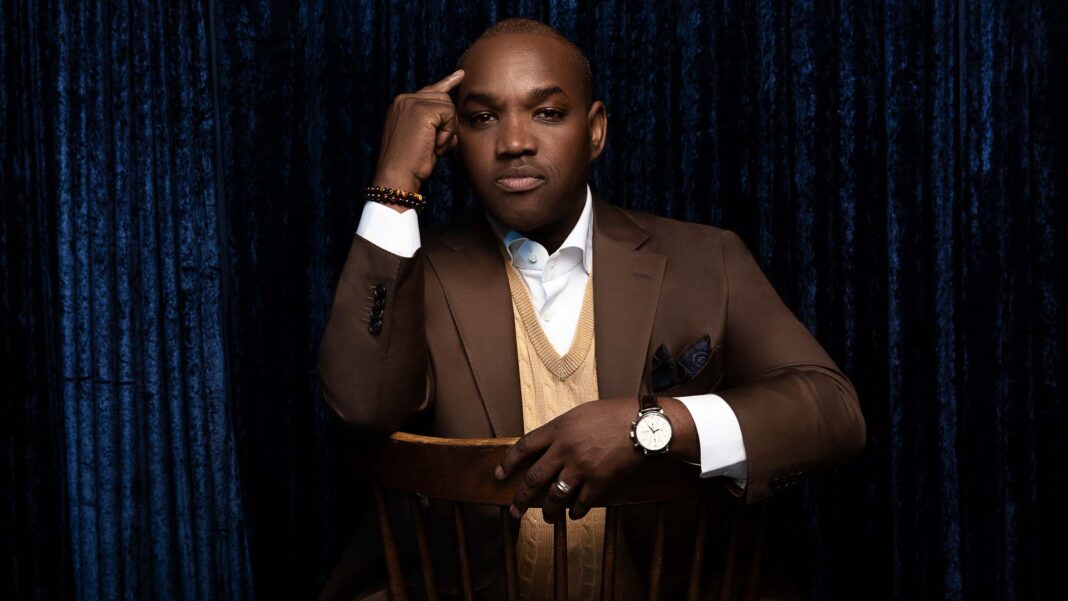

Main Photo: Lawrence Brownlee (Photo by Zakiyah Caldwell Burroughs/Courtesy Warner Classics)