Composer Anna Thorvalsdottir is massively busy. This month, and for the next several months, she and/or her music will be everywhere. Sono Luminus released an album by the Iceland Symphony Orchestra last month, Atmospheriques, that opens with Thorvalsdottir’s Catamorphosis.

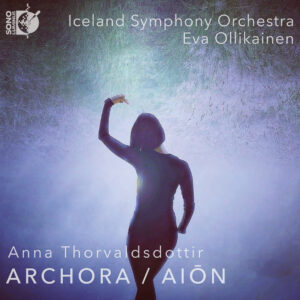

On May 26th the same label will release the world premiere recordings of her AIŌN and ARCHORA. The latter work had its world premiere last year with Eva Ollikainen conducting the BBC Philharmonic Orchestra. She leads the Iceland Symphony Orchestra in this recording. Ollikainen will also be leading the Los Angeles Philharmonic in the US premiere of ARCHORA in three concerts beginning Thursday, May 11th.

This summer she is co-curator of the Festival of Contemporary Music at Tanglewood. She is joined by Reena Esmail, Gabriela Lena Frank and Tebogo Monnakgotla as co-curators.

The festival, which takes place July 27th – July 31st will showcase Spectra, Reminiscence I, II, III, IV, V, VI, and VII, Hrim, Aequilibria, and Ró – all works by Thorvalsdottir on July 28th. The closing program on July 31st will also feature her work METACOSMOS.

Last week I spoke with Thorvalsdottir about her approach to composition, the use of drawings to capture her thoughts before composition and the intense interest in Icelandic composers today. What follows are excerpts from our conversation that have been edited for length and clarity.

You have discussed in previous interviews about creating a state of mind that you described as “caution, but determination.” How much do caution and determination play a part in your composing?

That’s a good question. Caution and determination. In my composition, when I’m finding and searching for the music that I’m writing, I always approach that open and allow for the right ideas to come and to turn into what it is that the music wants to become. For me, openness in the creative process is probably the most important element. And that also more specifically requires head space.

I don’t think about the creative process in other terms fundamentally. Obviously when you’re farther along in the composition process, you’re orchestrating and working with material in meticulous ways. That’s when you have to balance the techniques versus the atmosphere and find the right ways to communicate the things that the music is.

Other composers often say they’re just a vessel for what comes to them. Do you feel similarly?

Absolutely. It’s an interesting thing because this is something that is often hard to describe in words because this is not a process that emerges with words or phrases. I think that means that we interpret it like something that comes through us, what comes to us. In that process is so much evaluating and going back and forth between ideas. Each idea will then grow into different ideas and grow branches and roots. So it’s about evaluating many different aspects, every part of the way.

It almost seems foolish to try to discuss what composition is for any individual composer because, like you just said, it’s not a word-driven creative act.

Right. It’s something that does not come from words, not unless you are writing an opera with the libretto that you’re trying to convey a storyline. It’s an intuitive thing, just like any art. If you think about it, if you’re writing a paper or an article, it might be difficult to describe the thing that you are doing whilst writing. It’s just difficult to describe creative processes, I think.

I do find it interesting that you employ the use of drawings as a source of inspiration; the first pass of an idea is something that’s been drawn as opposed to something that’s been notated.

These sketches are merely a mnemonic device. The sketches emerge from the music that I am listening to internally. They emerge as representations for myself to remember the music that I’m experiencing because it takes a long time to notate a score, especially if it’s a large score for 100 performers.

Then the sketches start to get added to and they start to materialize the ideas in different ways and for different pieces. This will always have its own unique process for every single piece. But it is, for myself, a way to remember the internal listenings that I am meditating on or dreaming on.

ARCHORA had its world premiere last August at BBC Proms by the BBC Philharmonic. It is just now having its U.S. premiere, but there have been other performances and there is a recording that is coming out soon. After that first performance, did you revisit the work at all? Is there anything you learned from that performance or is the work done and you move on?

The reason I’ve never edited a piece after performance is that in the composition process I really obsess so much over every single detail. I never hand in a score unless I am absolutely certain that it is ready. I have never edited a piece after performance, but of course I would if I would feel that it would need to be edited.

I’m going to try to describe my response to listening to ARCHORA because I found my breathing changing in peaks and valleys along with your music. I found that I got very still at moments; almost meditative. There were other moments as it turned up a bit more angst that my breathing changed in relation to that level of energy. Is that something that you hope a listener is going to do?

I absolutely love that experience. When you approach music so openly that you completely dive in and become part of that music, I really love that. I always appreciate so much to hear people’s experiences and how they relate to the music. When you’re writing a piece of music you cannot control how people are going to react to it. You can only open yourself up and create the music that you want to bring into the world and invite people to have their own experience.

In ARCHORA there are these opposing forces, these calmer elements versus the more dark sound elements, that are balancing each other throughout the entire piece. I think it’s wonderful that you got so involved that you kind of became the music.

If we want to hear mostly newer pieces, we could go to the album Atmospherqieus that was just released with the Iceland Symphony Orchestra under the baton of Daníel Bjarnason. The album includes one of Missy Mazzoli’s works, who is the only non-Icelandic composer on the album. There’s a work by Daníel and two other composers from Iceland. Do you feel like we are in a golden age of of contemporary classical music coming out of Iceland?

I definitely think that there has been a real nice growth in contemporary music everywhere, not just in Iceland. But there has been a nice focus on Iceland lately and it’s wonderful to see that. We stand on the shoulders of of many giants. I think the different genres of music in Iceland that have been more popular, are still and have been more popular in the past, have helped us to shed a light on the contemporary classical scene in Iceland.

And it’s good that the world now knows that there’s more than Björk.

Björk is, of course, our godmother of Icelandic music. We owe her so much and she’s amazing.

You have the album that came out last month. You have the album coming out at the end of May. You’re getting performances of these works now, but these are works and recordings that have been completed for quite some time. What is your focus now and what is it you want to spend your time doing moving forward?

I always have a five-year schedule of commissions lined up and I’m always working on huge projects. So as I have been in the last few years and I’m continuing to do so, I have many projects on the schedule, which are very exciting. And a lot of performances which is a luxury.

Plus a lot of residencies coming up here in the UK and also in the US at Tanglewood this summer. The job of a composer is a lot more complicated than only writing music.

But at the moment I’m working on another orchestral piece or an orchestral installation and a cello concerto. There’s always so many things going on. I don’t know even where to start.

How much does your work reflect how you are feeling emotionally about the world we live in? Do you feel in this time, where there’s as as much turmoil as there is joy, optimistic about the future of us as a civilization? What do you think the future has for our civilization?

As a person I am really optimistic. Of course, I am human and we are not always optimistic. But I do try to believe so much in the good that I have to always be positive and optimistic.

Your first question in this cluster of questions was also how the emotional state affects the music that I’m writing. It absolutely does. A lot of the ideas and inspirations that I talk about are more often than not metaphors. It’s impossible to live in this world and be an artist without having all the things in this world affecting you in one way or another while you’re working. I am no different than everybody else when it comes to that.

Main Photo: Anna Thorvaldsdottir (Photo by Anna Maggý/Courtesy the composer)