Tonight is the opening night of the musical Beetlejuice at the Pantages Theatre in Hollywood. Having attending many an opening night there, I know exactly what to expect. At the very hint of the start of the show, the audience will go absolutely wild as if the biggest star in the world was about to take the stage.

I was naive/skeptical enough to think this only happened at the Pantages. I imagined they brought in a large group of paid attendees to ramp up the excitement on opening night. Boy was I mistaken.

Recently I had a few days in New York to catch up on some shows: Some Like It Hot; Sweeney Todd; Kimberly Akimbo and Good Night, Oscar. The same boisterous response to the start of each musical (perhaps plays don’t attract either the same audience or the same frenzy) preceded the first downbeat from the conductor to get the musicals started.

This phenomenon forced me to ask a lot of questions. First and foremost was why was this happening. It can’t be just that Sweeney Todd is a known property, because that would negate the same experience at the lesser-known Some Like It Hot. (It, too, is based on a known property, but only known for those for whom I don’t have to detail how and why it would be known.)

The Tony Award-winning Best Musical Kimberly Akimbo audience didn’t achieve the decibel level of the other two shows. Was that the smaller venue or the more quiet nature of the musical? Don’t get me wrong, that audience was passionate, too.

Then it occurred to me. Audiences have been trained to be overly excited at the start of television competition shows that feature live performance such as American Idol; America’s Got Talent and The Voice. Whenever a singer hits a relatively high note, or can sustain it for more than a few seconds, the audience goes crazy. They do it again and again and again for repeated displays of vocal calisthenics. Every time a little bit of talent is on display in a slightly impressive way, the audience is off and running with a level of robust applause that ultimately drowns out the very talent they are celebrating.

Why can’t we let a singer, or a musical, earn our respect? Does everyone believe, much like the speakers used by Spinal Tap, that everything has to go to eleven? And if it starts at eleven, where can it go from there?

Is the very price of seeing one of these shows the motivation for celebrating the fact one could afford to be there? Just as the now guaranteed standing ovation at the end of every show is as much a celebration for having made it all the way to the end as it is a way to acknowledge the talented people on the stage and in the orchestra pit.

What is earned and what is deserved? What is the definition of talent today? Not every show deserves as standing ovation. I’m sure we all have those shows that leave us scratching our heads about what anyone ever saw in them. Nor does every vocal trick require the inevitable ovation that seems to accompany them all.

In Beetlejuice they sing about That Beautiful Sound early in Act II. Perhaps the casts of all these shows think this outpouring of emotion at the start of every performance is the energy boost they need and these ovations are that beautiful sound they covet.

I’ll take my cue from the title of a different song in Act I of Beetlejuice: Ready Set, Not Yet.

What do you think either as an audience member of someone who makes their living in theater? Leave us your thoughts in the comment section.

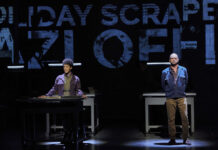

Main Photo: Britney Coleman, Will Burton, Isabella Esler and Justin Collette in “Beetlejuice” (Photo by Matthew Murphy/Courtesy Broadway in Hollywood)