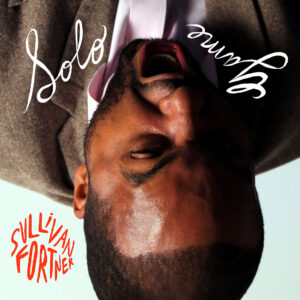

My first introduction to pianist Sullivan Fortner was seeing him in several concerts with Cécile McLorin Salvant. He was more than her accompanist, he was her musical partner. From there I explored his solo recordings. Nothing, however, prepared me for his bold new album Solo Game on Artwork Records

This is a two-disc recording in which the first half finds Sullivan performing solo piano. Each song was performed just once and there are no overdubs and there’s no editing. This part, Solo, was produced by Fred Hersch.

The second part, Game, finds Fortner making use of many of the tools artists use to perfect their recordings, but he uses them to help create music rather than correct was has been recorded. The cumulative effect of the album is to see jazz as a constantly fluid genre of music and Fortner with one foot standing on the shoulders of the legends before him and the other firmly striding forward to the future.

In early December I spoke with Fortner about Solo Game, his working with Hersch and Salvant and what he requires from his art and what his art requires from him. What follows are excerpts from our conversation that have been edited for length and clarity. To see the full interview, please go to our YouTube channel.

Q: Miles Davis is quoted as saying, “You should never be comfortable, man. Being comfortable fouled up a lot of musicians.” How do you think being comfortable fouls up audiences? I ask that because I think your album is not comfortable and challenges audiences to eliminate any preconceived ideas they might have.

For better or for worse, for an artist, I think it’s important to constantly push. And I think as an audience member, at least for me, and the people that I talked to about it, they don’t like to see people perform and be too comfortable. They like to see some sort of struggle. I think one thing that the pandemic kind of brought a little bit more to light is the idea of watching people’s processes and watching how people create. The idea of watching people go through things and figure out formulas and struggle, make a mistake and then do it over.

It brings a certain type of humanity to the art or to whatever it is that they’re creating. One of the things I try to do is I try to create real performances. If it’s a little bit too perfect, then it doesn’t seem real to me. It’s not human. You know, the imperfections are the things that make music alive and beautiful.

How much do you think an audience is aware of that struggle?

I think we give the audience a little bit less credit than than than we probably should. But I also think that if there’s a type of banter or type of communication that happens within the bandstand, then people can get that. They’re like, Oh my God, what’s getting ready to happen next? Oh, the drummer’s going crazy. Something happened. You know what I mean? The drummer just gave the bass player a look. Oh, he didn’t like him too much, you know? Stuff like that.

What is the conversation you are having between Solo and Game, and how does that give us a better understanding of who Sullivan Fortner is?

I wanted both Solo and Game to reflect Sullivan Fortner. Not so much the pianist, but the artist, the musician and the thinker. Both sides of the album were exposing me. Acoustic being, okay, I’m playing by myself, completely acoustic piano. No edits, notes, no second takes, nothing. Then the other side being, okay, now I get to play whatever it is I want to play, but on instruments that I’ve never played before. Just experimenting with limitations.

Both of them had that idea of experimenting within a certain type of parameter limitation. Both of them kind of question the idea of when we play music, do we actually play music? It underlined that word play. So when you think of that word play, you think of arcade games. Both sides of the album there are various games that are constantly being played. Both sides reflect each other.

How important is it for you for the tradition of jazz music to evolve as it always has and as it inevitably will?

I think that it’s extremely important. I think it’s also important for jazz musicians to use the tools of the studio. I had a conversation with a great musician and great friend of mine who basically said when we go in the studio as jazz musicians, nine times out of ten, we use Pro Tools to edit a part that we don’t like. We use ProTools or Auto-Tune to correct the note or to fix whatever. They don’t use the studio and use those programs to help as an extra instrument for the music. You know what I’m saying? So what I wanted to do in this album, especially with the Game part, I wanted to use pitch correction as a part of the music and not to fix whatever I did that was wrong.

As an compositional tool instead of a correctional tool.

You said it exactly the way I want to see it. I also think that it’s important for the musicians to not be so precious with the studio. The idea of it wasn’t necessarily be perfect. It was to be honest and show a real representation of who I am and where I am at that particular time. A lot of times, especially younger jazz musicians, we’re all so gung-ho about creating the perfect album rather than creating an honest album. This album that I created by no means is perfect. I already know, but I know that I can honestly say I’m proud of it because it’s the most me that I’ve ever created.

How long has this other side that wanted to play in the studio, that wanted to to not be afraid of the studio, not be afraid of the technology, been buried inside you?

If I’m honest COVID actually birthed that side of me. The first instrument that I grew up playing was a Hammond organ before I started playing piano. My first love was the organ. So electronics and manipulating sounds within the capabilities of an electronic instrument was something had always been in me since I was seven years old. I’d never really owned a piano when I grew up. I only owned keyboards, but I would just stick to the piano parts and try to manipulate the piano parts. Maybe there would be some times where I could record on the keyboard. I would add instruments just with keyboard patch. But that was just for fun. But the idea of actually going in the studio and doing that was inspired by COVID and Cécile McLorin Salvant.

She keeps subtly reinventing herself. That’s the thing I love about her. They’re not radical shifts. It’s not like suddenly Bob Dylan is playing an electric guitar. There are these subtle shifts and every one of them makes sense. That has to be an inspiration.

It is. Being on the side of the stage that I sit on, whenever I see her and the more I get to know her, the more I realize that she’s becoming more and more herself every album. I think that’s the most inspiring thing to watch her evolve as an individual, as a woman, as a human being on this planet and as an artist. Watching her just really step into what makes her unique and special in her eyes. That’s the most inspiring thing, just her being excited about her being herself.

I’ve seen you with Cécile multiple times. It strikes me that the two of you do not have a traditional vocalist and accompanist relationship. When I see Cécile McLorin Salvant and you’re on the stage with her, it might as well be Cécile McLorin Salvant and Sullivan Fortner, because you two are so intrinsically tied to one another musically. Does this feel like a unique collaboration that is different than what you have seen or witnessed or even experienced as a pianist and a vocalist working together?

Yeah, it most definitely has. And it was like that from the first time we played together. From the very first note, it felt like we were immediately at home. At least it felt like I was. You’re playing with somebody that has that certain type of independence where you don’t feel like they are relying on you to make something happen.

We definitely are individuals. But for the first time, I actually felt like I could play with somebody that I could grow with. You know what I mean? It wasn’t waiting on me to play catch up.

In 2016, you told the Oberlin Revue that “Music is like a drug. You’re chasing that first high….the high you got..the first time I played music and really enjoyed it. Since then, I’ve been trying to chase that feeling.” What was that feeling you were chasing with Solo Game? What was the high?

You want the honest answer? I went in the studio nervous and Cécile said, just go in and relax. So I took an edible before I went in the studio. So that automatically relaxed [me] and that got rid of the nervousness. But I think the high that I was chasing was just that feeling that I got when I was a kid and I didn’t know anything. I was just happy to play. You know what I mean? I didn’t know. I didn’t know any complicated chords. I could only play in like four or five keys. There was not really a whole lot of harmonic sophistication. There wasn’t a whole lot of rhythmic sophistication. It was just me playing the songs to the choir. I didn’t know anything. I was just happy to play. That was the high that I was chased.

Did it take a lot to be comfortable in the recording of this particular album? You were working with Fred Hirsch who, along with Jason Moran, complete the album with their own comments about you and this project.

Fred is not an easy person to please. He a very nice man; extremely nice. Been very kind to me. But he’s definitely particular about what it is that he likes. So whenever you’re in a room with somebody like that, you always you automatically feel this pressure of doing anything that you possibly can in order for it to sound good.

I think with Game, it’s a little bit more like I was left up to my own antics. It was fun making it. But I had to suffer when I was shopping the album around. I had a little bit of difficulty trying to find a home for it and people who actually wanted to support it, to back it up and help me put it out because it was so different and so unorthodox.

I’m assuming you probably got a lot of offers to release the first half, Solo.

Here’s the funny part. When I shopped that around, I only shopped around Game, minus the edits and all the added sound effects. Once I found a label that was interested in that, then I gave them the acoustic album and said, Okay, I want both of these to come out at the same time as one album. They were like, we’ll put up the acoustic album, no problem. But this other one we got to wait. I said nope it is either both of them, or none of it. It took a lot of guts and I almost gave in. But, thanks again to Cécile and to Jason Moran, they were like, no, this is what you want to do. You need to do it that way.

It makes sense that Jason would be a supporter of doing that. If you look at how his career is started and what he’s doing now.

In the last two years basically every piano player, every major piano player, people who are soon to be major, in my opinion, have released solo albums. Jason Moran. Brad Mehldau. Ethan Iverson. Kevin Hays. Vijay Iyer. Fred Hersch. They’ve all released solo albums, especially during Covid, because there was nothing else to do. If I was going to do a solo album, I wanted it to stick out more than just be acoustic piano. I wanted it to be an all-encompassing solo situation. So part of it was sticking out. The other thing was I wanted to make a statement that I’m not just a piano player. I’m also someone that has an idea or a vision musically that goes beyond just the eighty eight key box.

Solo Game was recorded during the pandemic and it took a while, as you mentioned, to shop it around and find somebody who was going to release it. But that’s given you all kinds of time to develop new ideas and new ways of expressing yourself. Where are you headed with new material now?

I’m thinking about continuing along this path; especially in the studio. Going back to using the tools that are available in the studio as a part of the composition. The next project that I’m working on is a trio album. It won’t be a double album, but it will be two different trios. One trio would be with Marcus Gilmore and Peter Washington and another trio would be with Tyrone Allen and Kayvon Gordon, who are a group of guys that I’ve been playing with for the last year or two. They’re a lot of fun to play with.

That’s the next thing to try to figure out. It’ll be a mixture of originals and standards, a little bit more towards the traditional side, but with few surprises maybe. And after that, I think the next thing I want to do is a choral album which would feature just piano for the most part and vocals with my family singing. So I’m in the process of writing stuff like that. I’m trying to continue along in the vein of Game and building a catalog as opposed to creating separate worlds that each album stands in and lives in.

I want to ask you about something Duke Ellington is quoted as saying. He said “Art is dangerous. It is one of the attractions; when it ceases to be dangerous, you don’t want it.” For you personally, what do you want most from your art today, and what do you think your art wants most from you?

I guess the art wants from me fearlessness. Not being afraid to try and not being afraid to step out there. Being you and being confident in that.

What do I want my art to give me? I want the art to just continue to give me what it’s already given me, which is a sense of purpose and being able to continue to help me articulate what it is I can’t say in words. To help me to discover more about myself and discover more about the world around me. Art teaches me music and art teaches me about life and learning how to get along well with others, to compromise, to live in harmony and peace and balance. That’s the stuff that art gives me and I want it to continue to.

To see the full interview with Sullivan Fortner, please go here.

All photos of Sullivan Fortner: ©Sabrina Santiago/Courtesy Artwork Records