Composer George Gershwin did not know he was expected to write a new work for a concert that Paul Whiteman called An Experiment in Modern Music until his brother Ira read about it in the paper several weeks earlier. Gershwin went to work and the end result was Rhapsody in Blue.

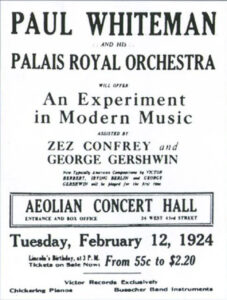

That concert took place at 3:00 PM on February 12, 1924 at Aeolian Concert Hall which stood just east of 6th Avenue in Manhattan. (Go to this link to hear a 1924 recording with Gershwin at the piano with Paul Whiteman and his orchestra).

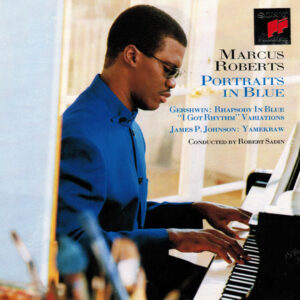

Since that jazz band version (arranged by Ferde Grofé) there has been the fully-orchestrated concert version (the standard version heard played by symphonies around the world) and multiple re-workings of Rhapsody in Blue by artists ranging from Billy Strayhorn and Duke Ellington to Chick Corea, Marcus Roberts (on his album Portraits in Blue) and a new re-imaginging that was released recently by pianist Lara Downes with composer/percussionist Edmar Colón.

I recently spoke with Roberts, Downes and St. Louis Symphony Orchestra’s Conductor Laureate Leonard Slatkin, whose 1974 recording of Rhapsody in Blue is one of the first recordings I owned. We discussed their first memories of hearing the piece; its longevity and appeal and also a recent article written by Ethan Iverson for the New York Times.

You can read Iverson’s full story here, but he says, in part, “If Rhapsody in Blue is a masterpiece, it might be the worst masterpiece. The promise of a true fusion on the concert stage basically starts and ends with it. A hundred years later, most popular Black music is separate from the world of formal composition, while most American concert musicians can’t relate to a score with a folkloric attitude, let alone swing.”

What follows are excerpts that have been edited for length and clarity. You can see all three of my interviews on our YouTube channel.

DOWNES: I have this fuzzy memory of hearing the bit you would imagine used for figure skating in the Olympics. That’s one of my earliest memories I can pinpoint.

SLATKIN: Actually it’s so long ago, I don’t think I remember, but I suspect that like everybody else, the first thing was the clarinet at the beginning more than the piano part. It was a sound that we really hadn’t heard before.

ROBERTS: I was a child, probably 12 years old, maybe 13. The funny thing is I remember hearing the piece, but when I first heard it, I didn’t know that’s what it was called. I think I heard it on the radio, maybe in the middle of it or something and I was really attracted to it. It was soulful. I could tell it had something in it that I could identify with. And of course, years later, I figured out that it was indeed Rhapsody in Blue.

SLATKIN: I hung out with a lot of jazz musicians, but I didn’t know so much about big band jazz. So this idea that whether it appeared in a symphonic form or in a band version didn’t really strike me as anything other than something very unusual that I wasn’t used to.

ROBERTS: Now that I’m grown up and I’ve been out here playing a long time, I don’t know if I was thinking this way as a kid, but I think it was the fact that the themes were relatable to me, meaning they seemed to come right out of my cultural experience.

DOWNES: What was happening in American music and all of the things that were coming together and all the things that were changing so fast. Understanding what was happening in Black music at that time in the early part of the 20th century and this hybrid language that was developing.

SLATKIN: In order to understand that, we have to go back to that first performance and understand why it was so important. This concert is organized by Paul Whiteman – An Experiment in Modern Music. We didn’t really have American music for the concert hall. Yes, there were composers in America, and yes, many of them were born in the States. But the sound of the music itself reflected a more European tradition.

We’re not talking about an original American music. We’re talking about borrowed music from church, from patriotic songs, from folk music. We didn’t have anything we could call our own. That’s coming up via the emerging popular music scene, probably starting with ragtime. The vernacular music of the time tended to be shorter pieces 3 or 4 minutes long. Now, all of a sudden, a large scale work 15 16 minutes was appearing. This audience, which included some of the most distinguished musicians in New York at the time, was stunned by what they heard.

ROBERTS: He’s using American themes. He’s using themes that clearly come out of the African American experience. And as Dvorak said, that’s really the cultural identity of the country. That’s where the themes should primarily come from. Not exclusively, but that’s the richest soil that we have.

DOWNES: [When] we look at the core tradition of classical music, what we’re looking at is [often] this interchange between structured music and the vernacular. The folk music that gets absorbed into the music of Brahms and Liszt to Dvorak and everybody. So I think it’s a continuation of a tradition. I also like to look at this as omnidirectional. Gershwin is leaning back, he’s looking forward. He’s got all these things kind of pushing and pulling at him. And what he comes up with is very emblematic of its time.

SLATKIN: It’s an immediate sensation. All of a sudden composers in this country said, we have the room to grow within our own culture, within our own sound world. And from that point on, composers now began to gravitate from one world into the other.

ROBERTS: So I think that it’s ripe for improvisation because the rhythms are clear. You can hear the blues element in the melodies. When I did Portraits of Blue back in 1996, a lot of critics were not too happy about it at the time. Of course, there’s the Ellington version of it. Nobody really did it, though, with the real intention of improvising on it and bringing it literally into the jazz environment with the specific agenda of improvising on it and recreating it. Me doing that has made it clear that not only can you do it, but you should do it, and there should be many versions of it where people can do what they want with it.

SLATKIN: Even Gershwin himself added little things in different performances. I think one of the reasons that this works as an improvisatory piece, even though everything is written out by Gershwin, is because it’s essentially a number of cadenzas where the orchestra is not playing.

DOWNES: I always experience it as a dialog. I really do. I have a close relationship with the solo piano version of the piece. I play that a lot, too. So what that means is that when I play the Grofé version with an orchestra, I have to remember what not to play. But I feel very intimately involved with those orchestra bits because I need to play them myself. I’m not sure that I have an objective view of the structure, but that is something that we wanted to expand and embrace was the improvisational nature and opportunity.

ROBERTS: In the original score, it basically says something to the equivalent of wait for George to nod or something or watch George. So he was he was probably improvising on it himself when he premiered it at Aeolian Hall in 1924.

DOWNES: I think that the further that we’ve gotten from 1924, as we always do, we have started more and more setting that thing in stone, which it wasn’t originally. When you talk about Ellington and Strayhorn, they’re not that far out from the 20s. Grofé did the version in 24 and then the version with orchestra from 1942. I feel like these 100 year anniversaries, it’s important not to put things in a museum when they get to be 100 years old.

I think it’s an interesting thing that we don’t do in the world of classical music very much. There’s some of it, but we don’t tend to re-arrange, reconsider, review, re-imagine. It’s really funny for me when I work with musicians from other traditions and they’re like, you do what? You play the same notes the same way over and over again?

ROBERTS: And I think that’s what ultimately made me want to do something different with it. The goal for me is to present the piano based on all of the music that I’ve heard in my life up till now. What is it that I understand and put it in that context.

SLATKIN: I think it’s not even fair to call this work a piece of cultural appropriation, because it doesn’t reflect what the Black musicians of the times were doing. They were going in a whole different direction. And yes, that music would pave the way for innovators such as Ellington and so many others.

DOWNES: There have been all along massive problems of inequity in the music world that were institutional. There have been a lot of closed doors and a lack of access. I don’t think that fits with the musicians themselves. I think that sits with institutional structures. I think that what musicians have always done well is listening. And I think that we listen to each other and we learn from each other and whatever is happening in our air around us, we absorb. We can’t help it unless we want to keep our heads under a rock.

ROBERTS: It’s been a struggle. There’s no secret there. There’s obviously been a lot of struggle with minorities in this country. Not just in terms of opportunities in music, but with a bunch of stuff. The fact is, had he not written it, I think there still would have been struggle. So I like to look at it more from the standpoint that he did it. It has opened up, frankly, eventually opportunities for people to still do whatever it was that they were going to do.

DOWNES: I’m so fascinated with that time in the 1920s, in the 30s. Things were changing so fast. People were encountering each other for the first time and everything was new. Jazz was new, and it was a very different thing than it is now. Just even to look at Gershwin’s very short lifetime, his 24-25 years before he wrote Rhapsody in Blue, all the things that are so quickly moving through but accumulating: the Yiddish theater and vaudeville and the beginnings of the Great American Songbook. It’s all coming together.

SLATKIN: Gershwin didn’t intend that when he wrote it. It wasn’t I’m going to write something and therefore nobody else can go this direction ever again. Gershwin was in his own groove. He came from Tin Pan Alley. Those are people who went from door to door just pitching tunes to publishers. Most music was sold in sheet music fashion for people to play at home. Within the Black culture that was probably not the case. This was passed on more through different means. Ragtime, as practiced, say, in New Orleans or other places, was mostly an improvisatory field. It wasn’t really written out yet.

ROBERTS: It’s not just George Gershwin. It’s not like it’s George Gershwin’s fault that he did that right. I just think the main thing that we have to focus one in this country is let’s see if we can get away from doing stuff like that. Let’s really use all of our efforts, all of our collective power, to include people and give them opportunity to succeed regardless of race, creed or gender.

SLATKIN: It’s not felt as a work that’s exclusive to one audience. Timeless works are that way for a reason, because they go over these boundaries. Rhapsody in Blue was different for its time. Could Ellington and others have appeared and done this kind of work earlier if Gershwin hadn’t done it? Maybe. But probably not. And anyway, if they wanted to go that direction, they would have done it regardless of what Gershwin did.

DOWNES: I do think that there’s a reason that things last. The piece has proven itself 100 years later and I would just love to see it continue to grow. Because I do think that was Gershwin’s intention. This musical kaleidoscope that speaks to me of endless possibility and shifts.

SLATKIN: Gershwin was all about moving forward with music. Leonard Bernstein talked about how he really was not happy that so many people knew him from West Side Story. Gershwin, I think, would have said, I’m thrilled that the Rhapsody has reached this kind of audience. And I’m pleased that my other works have also done this. He’s always the classic example, along with Mozart and Schubert, of saying what would have happened if he’d lived longer? Let’s just take what we’ve got, because what we’ve got is not bad.

ROBERTS: The attitude I have is that it’s a living work. It’s a living document. I feel like that simply is one of these pieces that’s alive every time we play it. I hope that it’ll be around for another 100 years. And I hope that there’ll be other music that America will fall in love with, that we can continue to have similar ways to collaborate jazz and classical music.

To see my Rhapsody in Blue interview with Lara Downes and to hear more about her new album, please go here.

To see my Rhapsody in Blue interview with Marcus Roberts and to hear some exciting news about upcoming albums, please go here.

To see my Rhapsody in Blue interview with Leonard Slatkin, please go here.

Main Photo: George Gershwin (Courtesy the Billy Rose Collection/New York Public Library Archives)