Jazz pianist and composer Fred Hersch is about as prolific an artist as any in the genre. He’s released well over 50 albums as a bandleader or co-leader (which doesn’t count the numerous albums on which he is a featured soloist). His latest album, Silent, Listening on ECM Records, finds him working again as a solo artist. This time with producer Manfred Eicher (founder of ECM Records).

The comma in the album’s title is important to Hersch. Silent isn’t describing the listening. Being silent and listening are two distinctly separate qualities that were of paramount importance to him while recording Silent, Listening and the qualities he hopes listeners might employ when they put on the album. Which they should.

I recently spoke with Hersch about his concepts for this album, how the resurgence of vinyl impacts the albums he’s making and how he’s challenging himself to do something we haven’t heard before. What follows are excerpts from our conversation that have been edited for length and clarity. To watch the full interview with Fred Hersch, please go to our YouTube channel.

Q: What is the role of silence in your music and in your life?

Without silence you can’t have music or much of anything else. This is maybe my 12th or 13th solo album. I think the title of this project partially refers to the the specific place and circumstances around the recording of the album. In a fantastic auditorium in Switzerland at the Swiss Radio in Lugano, a legendary auditorium, with superb acoustics, fantastic piano. I was prepared. I had some things that I wanted to play, but, I also left a lot open to the last minute.

I think there’s a lot of patience on this record; playing something and seeing how it lands. Play the next thing. As an improvising musician, that’s how you always want to be. You want to play the phrase and then see where it lands, and then the next thing comes. And if you have a goal or an expectation, then often you’ll be disappointed. Just like life. I like to be in that zone where I’m really minutely paying attention to each detail, which leads to the next thing. There’s a lot of what I call spontaneous composition on the record, open improvisation, whatever you want to call it. Just paying attention to the sonority, not the chord, just the actual sound. So sound was a factor and the beautiful silence that you get playing in a room like that.

I love the way you allow notes to just fade away. Then there’s a pause before you go on to something else. It feels like you’re not only allowing yourself to be patient, but you’re asking your listeners to be patient as well.

I think this record really unfolds almost like a suite. It’s kind of contra to the way that people consume music these days. I believe in the value of an album as a statement; a small film, if you will, a story. I think this album tells a story and builds on itself. A lot of the selections I didn’t plan to play. They just arrived. Certainly the spontaneous pieces just arrived, but when we put it together, we were totally in agreement about the sequence. It’s not just a series of tracks. It’s very much a unified statement. And the glue that holds it together is just sound. It’s a pretty immersive album.

In the press notes for this album you are quoted as wanting to have tell a story with this album. Yet, at the same time, you’re saying that some of the pieces just came to you as you were in the place. I’m assuming that you had the story deeply embedded into your heart and soul so that you knew what those pieces would be that came to you.

No. I had no title at all. I had a list of titles of artworks by Robert Rauschenberg. I would just assign, like Night Tide Light, that’s the title of a collage by Rauschenberg. Volon. I don’t know what volon means, but it’s an interesting word, so we just picked that. But the story emerged. There was no real intent. I think the story just arrived.

Manfred’s a great producer. What he says and also what he doesn’t say. Sometimes he just let me work stuff out. Other times he might say something. At one point he went into the audience, which was helpful. A couple of tunes I just played for fun, and he said, I really love those. I didn’t intend to play them. It was very much something that unfolded as we did it. But once we had the pieces, we completely agreed this is how the story gets told. Sometimes the pieces led very smoothly into each other. Sometimes there’s a very jarring contrast. It’s very cinematic, I think. But it wasn’t intentional. I just wanted to make a record with him in that place on that piano and see what happened. And so this is what happened right now.

I can’t help but believe that there is, whether intentional or not, a bit of a commentary about the cacophonous and easily-distracted world we live in.

Yeah, I mean, that would be really nice if people would slow down and paid attention. I play in concerts in my home club, the Village Vanguard, people are quiet. It’s maybe the one time in the day where they are away from their cell phone for 75 minutes – hopefully. The final track, Winter of My Discontent, I learned 45 years ago. The lyrics are really relevant to our time. Whenever I play any kind of standard or anything that has words, I’m really singing the words as I’m playing the melody. It helps me emotionally connect to the melody, but it also informs the way that I interpret it.

I listen to a lot of vinyl, so it’s like only a 22 minute a side commitment. Find time to put some music on and not while you’re on the treadmill or doing your email. Who knows how many people out there actually do that. But, without being fat-headed, I’d say that the people that do take the time to listen to this thing through, I think there’s a reward. We’re in the era of LPs coming back. When you make shorter albums, people are maybe a little more likely to actually dip into the whole thing. This record’s about 50 minutes. The one I did with Enrico Rava [The Song Is You] was 43 minutes. I think we’re in the era of not overdoing it. Less is more.

Is that better for you as an artist?

It is. I’m going to record a trio album for ECM next month. If it’s only a 45-minute album, that’s only going to be 6 or 7 pieces because there probably will be a bass solo or two and something for the drums to play. I’ve got probably a good 1500 vinyls and some of them I’ve had since childhood. It’s still the best delivery system for music sound wise. As I learned to play jazz, self-taught in Cincinnati, Ohio, in the early 70s, I would have one side of one LP on the turntable for days. I just keep listening to those four or five tracks over and over again and get to know them deeply. We’re in an age where everything is the algorithm says if you like that, listen to this. Everybody’s twitchy with their fingers. I think it’s great that LPs are coming back. To me, they never left.

I have noticed in the past couple of years, listening to artists like Gerald Clayton or Joel Ross or the half of Sullivan Fortner‘s Slow Game that you produced, artists in the jazz world are expressing themselves in a more quiet manner than they used to. Do you think there’s something going on in our world that’s inspiring it?

It’s a great question for which I don’t have an answer. There are incredible 40-and-under musicians or 30-and-under musicians. You mentioned players like Gerald Clayton or Sullivan – state of the art younger jazz pianists, in my estimation. Great instrumentalists and very deep in their way of playing the language and with their own perspectives. I have my ear to the ground. Certainly living in New York, I go out and hear people. I’ve taught a lot of these great younger pianists over the years. I always learn a lot from the way that they speak the language, which is different. I came to New York in 1977. The job description for being a working jazz pianist was you had to know tunes. You had to be able to swing. You had to be able to accompany. If you sight read, that was a bonus. But that was it. Now all the young musicians are expected to be composers and manage their internet empires and social media presences and produce their own albums.

Some of the people that you’re mentioning who are more mature, who are able to hold more stillness and withhold all the stuff that they could play, these are the more artistic ones, in my opinion. But for every one of those, there’s six more I could think of where it’s a lot of stuff that’s kind of forgettable. Nothing sticks. So stickiness in performance – improvisation, composition, is a quality that I value. It doesn’t have to be Andrew Lloyd Webber to be sticky, you know?

Sullivan Fortner told me that you were “an extremely nice man and that you’re not an easy person to please.” How easy or how challenging is it for you to please yourself, either when you’re composing or playing?

I can be a little tough on myself. I’m at that point in my career where I’ve done so many projects, to find something new, that’s where I am now. I don’t need to make another record just to make another record. I want to make something that represents growth. Something different.

I teach this all the time. Don’t obsess about what you’re not playing or what you wish you could play, or what you played yesterday that you can’t play today. Every time. Blank slate. If you make a mistake, use it. You already played it. There’s no point in tensing up about it. With Sullivan, when I’m dealing with somebody with a talent level like that, people don’t need to pay me to say, oh, you sound great. We were working together at the highest possible standard. It’s a pleasure and a gift to teach such talented individuals. I’m just really glad that people are really coming along to how great he is – finally.

You had him record just single takes of each song and I know you did far more songs that were released. How often do you rely on single takes for your own recordings?

On Silent, Listening I recorded the Russ Freeman tune The Wind. It’s the longest track on the album – seven minutes. The melody repeats twice. I just played the melody at the end. Both times I played a wrong note in the melody. Both repeats I played the wrong note. Same mistake, same place. The Fred of 20 years ago would never put that out. Like, people think I don’t know the melody. I’m always bugging people you don’t really know the melody. I made the same mistake twice. But there was magic in the take. Especially with things like ballads, you have to go with the feeling. To me, if I get a take and I’m really in the flow in it the whole way through, no lapses of concentration, it unfolds naturally, I won’t do another one because I might get, quote better. But then it’s going to be confusing later on between the take that has the vibe and the take that’s more perfect. I think I’ve learned to just leave things alone.

The best way to make an album for jazz like I do or Sullivan does is you prepare everything or you have an idea, but you leave it open for the magic to happen when the tape is rolling. If you figure it out and then execute it, to me that’s anti jazz. I don’t want to hear people regurgitate what they know. That’s not interesting to me. I want to hear people play what they don’t know. That’s when it gets good. Sullivan could just react and reaction is a huge part of being a jazz musician.

It’s everything, isn’t it? Listening and reacting.

Right! I got into jazz to play music with people and in front of people. Starting as a 5 or 6-year old, I liked to improvise and then discovered jazz. It was a great language for improvisation. Hanging out with all the people in the clubs was fun. It didn’t matter what your age was or your race was or where you came from. Everybody had this shared love of this music. Nobody’s making any money. It was kind of romantic in a way.

Reacting is when I’m playing trio. Yeah, I’m nominally the leader, but I’m really one third of what’s happening. So I have to allow the musicians to add what they do and allow myself to be inspired by them. In a duo, it’s even more intense because it’s just this intimate conversation. Solo, I am reacting to the feel of the piano under my hands, the touch and the actual sound in the room. And then the emotion of whatever piece I’m playing is a large part of it, too. I have to play the right piece at the right time in terms of the emotional connection that I could get.

To watch the full interview with Fred Hersch, please go here.

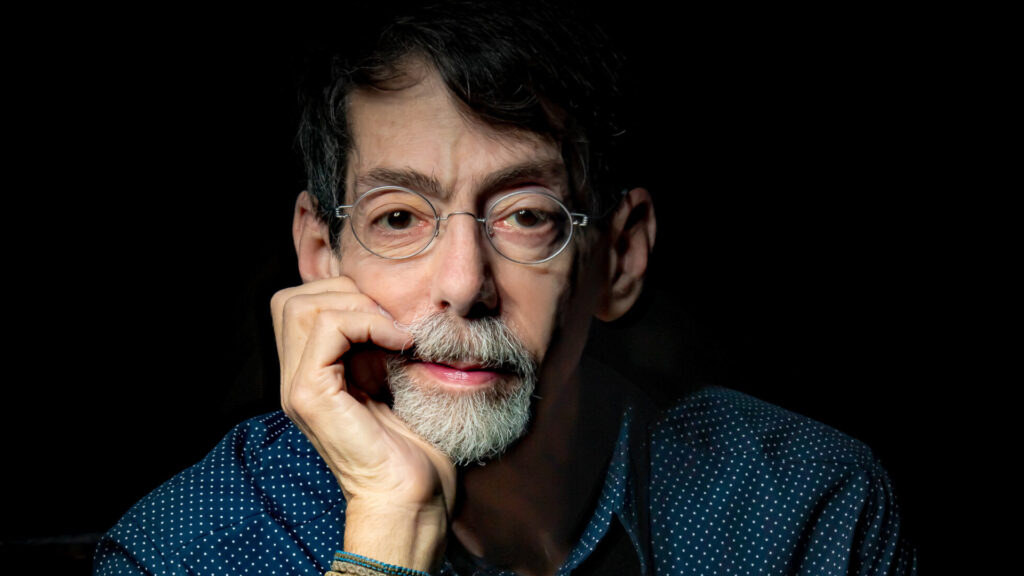

Main Photo: Fred Hersch (Photo by Roberto Cifarelli/Courtesy Fred Hersch)