Dancer/choreographer Victor Quijada grew up in Los Angeles. He is a first-generation Mexican-American. He got involved in breakdancing and hip-hop at an early age. He quickly earned the nickname Rubberband for the elasticity of his movement.

From there he went on to dance for and work with Rudy Perez, Twyla Tharp and Les Grands Ballet Canadiens. From there he founded his own company in 2002. He used his old nickname for his company.

Quijada, along with RUBBERBAND, will be performing Second Chances at BroadStage in Santa Monica on Saturday, March 8th and Sunday, March 9th. The program includes Trenzado and Commissions Suites.The latter allows Quijada to revisit two earlier works created for other dance companies: Physikal Linguistiks and Second Coming.

Last week I spoke with Quijada about the idea of second chances, the importance of being a true artist and what that means to him. What follows are excerpts from our conversation that have been edited for length and clarity.

To see the full interview with Quijada, please go to our YouTube channel.

Q: Twyla Tharp is quoted as having said, “Dance should not just divide people into audience and performers. Everyone should be a participant.” How much does that philosophy resonate with you, and how important is it for you to create a similar engagement with your own audience?

That is quite important to me. The way that I got into dance period was in circles where you’re the observer and the participant all at the same time. Versus being introduced to dance in a dance studio where you are facing the mirrors and there’s a teacher instructing you. That idea has shown up in my work a lot of different times, in a lot of different ways.

I wanted to take my choreographic exploration into spaces where there was no dividing line between who was doing and who was not doing. I think over the last 20 years, some of my work has really focused on erasing that fourth wall, whether the dances are spilling out over the proscenium thresholds or whether the audience is being called to action. Or if they’re just being asked to question the relationship of the dancers with the space, or the dancers with the music, or how they’re relating their experience to what I’m sharing on stage.

In Second Chances, one of the works that you’re going to be performing is Trenzado, which debuted in 2020. It marked your return to performance. What did that return mean to you and why was this the work that served as the best way for you to return to performance?

Through 2014, we were doing a residency and there was a scene shop and we were able to create a version of this set design. And in the other room I had my composer. I had given him a bunch of music that is very typical of what you would hear at my parents’ house when I grew up. What the set design was this broken outline of a home or the ruins of a house, and immediately I knew what the piece needed to be and the piece would need to speak about. I had left homes. I had left cultures. I had this identity crises of where do I belong as I move somewhere. I had become a father, which is one of the reasons that I had stopped performing, to concentrate on being a director.

It made me question also my father leaving Mexico and coming to the United States and what they chose to impart with me. A lot of different questions. It was pretty obvious that if I was going to talk about this, I was going to tell this story, I would probably need to be on stage to tell the story.

Second Chances allows you to revisit two other works that you had done for other companies. How has your second chance at revisiting these works allowed you to evaluate where you were at the time of their creation versus where you are today?

In 2010, when I created Physikal Linguistiks for Hubbard Street Dance Chicago, it was a big question in my mind. I couldn’t quite understand what was being expected of me when I was being hired as a commissioned choreographer. I knew I personally had this phobia, or this aversion, to repeating myself in creations. But I had this overwhelming feeling that I was being hired so that I could do a certain thing that I was known to do. And trying to figure out where a signature had evolved, but not using the same tools or giving the same results. I was in a very heady place.

The other piece that I revisited was Second Coming that I made for Scottish Dance Theater in 2014. I think in that era I wasn’t asking the same questions. I think I was a little bit more at ease with navigating where my signature was and what my tendencies might be. Also being okay with looking again at a theme, not repeating, but looking once again at a certain theme that had already been investigated. But looking for new facets and unwrapping new compartments within that investigation. I think those two bookend the trouble I had with figuring that out.

Is it easier to answer those questions now with more than a decade of experience beyond these works?

I think for me, and I’ve had this discussion with other people, why would you bring back old work? My goodness, I think it’s so valuable to revisit and to see where I was. And that’s what I did. It’s a way of time traveling. It’s a way of mentoring your old self. It’s a way of being mentored by your old self. It’s like going back into a journal and being like, wow, I think I figured that out, or wow, I’m still working on that. I think it’s incredible if you’re able to and you have the opportunity to.

In looking at the trailer for a Second Chances and the text that accompanies it on your YouTube page, you invite the audience and the dancers to reflect on origin, on belonging and displacement. How you think current events are going to magnify an audience response to those themes in this particular program?

In 2017, I had a residency at the Baryshnikov Arts Center in New York, where I started to put together a sketch of this. The piece does have some, I would say, controversial themes that we’re looking at. I felt the audience pushback or the how they received that. That was an important moment. Then I put it back on the shelf and I came back to it later. We were performing ten days before the election in Pennsylvania. We’re talking about identity and where you belong and finding your place. When I’ve showed the work to people, their energy is speaking a lot to me.

The work actually gives me a chance to kind of moderate and adjust and push more or receive less. So there’s a little bit of breathing room in the piece where I can ask for more or say, okay, we’ve had enough. I can use the energy in the room as a barometer of how far were we going to go or how far do we need to go. To really cross over into this fulcrum point where it’s that line between entertainment and art and something that you just watch or something that you’re involved in. Those are questions that I’m constantly holding on to and experimenting with.

The nice thing is when you’re dancing your own work, you can’t get mad at the dancer for having made some alterations in what was designed and choreographed.

You say that, but I have a lot of notes for myself after the show.

Do you think of your work as being political and at this point in 2025, is the sheer creation of art in and of itself a political act?

I think that second part, yes. More and more I think that. This may have been the most politically-angled work that I’ve ever made. I think for the first 15 years of my making stuff, I was really only focused on is it possible to take my street dance roots and everything I’ve acquired in the classical and concert dance world. And what happens if we let it coexist, and how will it affect each other. I was so preoccupied with that that once that was cooked, it was back to like, okay, what do you want to say with this language? There’s this whole technique that we’ve developed in this approach that helps dancers from different backgrounds come together and speak this language; this physical language that I’ve been developing. In 2018, ever so slightly, I created probably my first political work I’ve ever dared to make.

An important mentor of yours, Rudy Perez, asked in LA Dance Chronicle in 2018, “How does one become an artist today? A complete artist, to the extent that you can keep going?” How would you answer those questions that he asked?

It’s one of the most important things, because it’s one of the things that he would speak to me about every time we would speak and we spoke regularly. What Rudy wanted me to know was the most important thing was my relationships: my relationships with people, my intimate relationships, my friendships. To take care of that. And the human that Rudy was, was right there with the artist that he was.

There was a memorial for Rudy last April and everyone that spoke, spoke about how Rudy made them feel. The humanity and how special their interactions were. That goes beyond the artwork that goes beyond the performances, that goes beyond the statements that he made as an artist on stage. I think then to answer that question is to not let one overshadow the other. Not that you’re an artist and you can be a horrible human being. That being an artist and being a a good person are one and the same.

So would you define yourself as a complete artist at this point in your career using Rudy’s definition?

I’m doing my best. I’m doing my best.

To see the full interview with Victor Quijada, please go HERE.

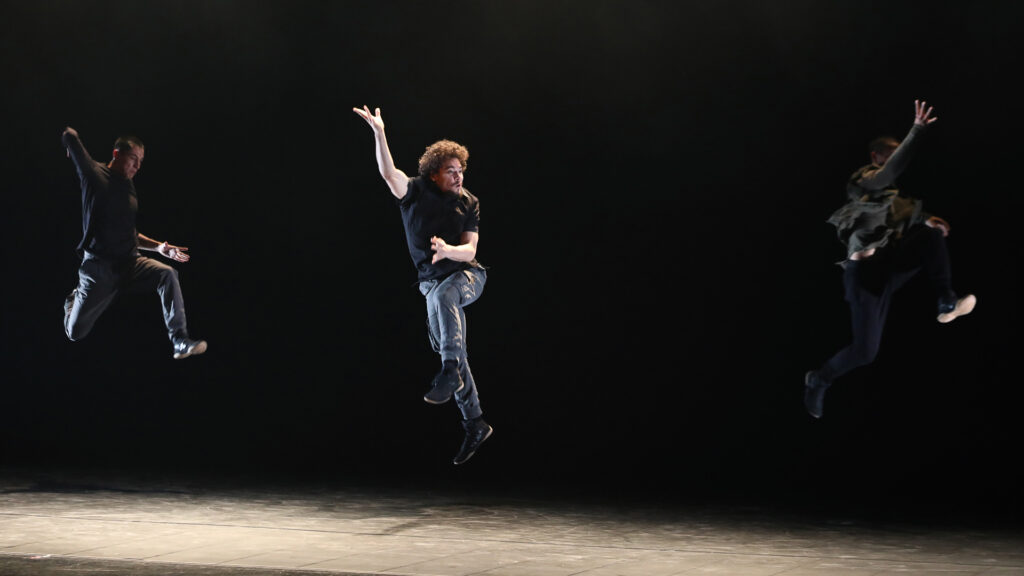

Main Photo: Vic’s Mix (Photo©Bill Hebert/Courtesy BroadStage)