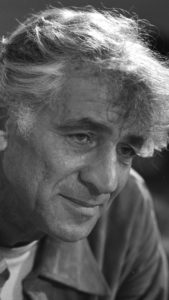

We probably all feel we know just about everything there is to know about composer/conductor Leonard Bernstein. As the years go by since his death over thirty years ago, just as we get comfortable with the idea that we do, it seems there’s suddenly more to learn about the man and his music. Just ask Flavio Chamis.

Brazilian-born Chamis, a composer and conductor himself, spent several years working with Bernstein in the mid 1980s. He also served as a guide to some of Bernstein’s less familiar music for the Smithsonian Jazz Masterworks Orchestra’s new recording, Bernstein Reimagined, which is being released on Friday. Big band arrangements have been made of some of the composer’s infrequently performed material.

Amongst the compositions being re-worked are excerpts from Mass, Trouble in Tahiti (his 1952 opera), Divertimento for Orchestra (written for the Boston Symphony Orchestra’s centennial),his 1965 choral composition Chichester Psalms and his score for the classic film On the Waterfront. The best-known work on the record comes from his musical On the Town.

I spoke by phone with Chamis earlier this month about his time with Bernstein, how the composer might view the concept of this recording and what it was like to experience Carnival in Rio with the maestro. These excerpts from our conversation have been edited for length and clarity.

There’s a vitality to Leonard Bernstein’s music and always has been. Bernstein Reimagined arranger Jay Ashby said, “Seven arrangers have really made it fresh. It’s really exciting how it brings new life to these compositions.” Did Bernstein’s music need freshening up?

I think Leonard Bernstein would be the first to agree that you would always find new things in old things. I was an assistant conductor of his and one of my most memorable memories was in Vienna. He was going to rehearse Schumann’s Third Symphony, a piece he had recorded multiple times and conducted on concerts and tours. He knew the piece. He cracked the score open and started looking at it and was discovering new things. He would be the first to agree with your question with a capital Y. Yes. That was the essence of Leonard Bernstein.

If he were to compare traditional recordings of Chichester Psalms with this new recording, would he recognize it?

Not only would he recognize it, I think honestly he would listen to this recording and say, “Wow, did I write this?” The structure of the piece is there, the melody is there. This is something that goes a step further. Listen to the original and compare to this recording. It’s all there. It’s a completely different take on the same thing.

You started working with Bernstein just after his opera version of West Side Story was released. Given what we experienced from that recording, a slower version of the musical than ever heard before, what does it tell us about his approach to re-interpretation?

The first days I ever met him he was listening to that recording. In general he recorded many pieces, not only his – many pieces of the classical repertoire, for second and sometimes third times. In general the interpretations were slower. There were more layers of depth in them. He never really recorded West Side Story before. It’s the only one he did. He had real opera singers, not musical singers. That is really what he wanted to frame there. I don’t know if it is how he felt or imagined the music in the first place.

If you listen to his Rite of Spring with the New York Philharmonic it is like a wild horse. Many years later with the Israel Philharmonic Orchestra it’s a completely different thing. It’s exactly how different an interpretation can be. It’s fascinating to see. You are talking a little bit like what jazz is. He was never a jazz musician, but jazz was in his personality. He would never do the same thing. I think it was Mahler who said, “If you find some real good reason to change something in my music, do it.”

Between your time with him and helping Smithsonian Jazz Masterworks Orchestra hone in on the right compositions for Bernstein Reimagined, do you think there’s unheard material, trunk songs or any other compositions that might someday come to light?

There are unfinished works. In the last years of his life he was planning on doing an opera using several languages. it never came to fruition. He wrote little excerpts of that. There are no full pieces he actually wrote. There are a few hidden songs he wrote for people. I was in Brazil with him for Carnival in 1985. He wrote a one-page song for a friend of ours who was having a birthday there. Maybe sometime in the future some little snippets would come out. It’s like when you find a new Mozart piece hidden in some vault that was discovered.

Bernstein in Rio for Carnival. That must have been something.

He told me one of his dreams was to spend a Carnival in Rio. It was at the time of West Side Story in 1984. In January he called me and said, “I rented a house. I’m going are you going?” I wouldn’t miss the opportunity to be in Rio with him. I just gathered all the money I had in my bank account and we were there in February. I was with my girlfriend. We saw everything. We heard that music – real samba sometimes played by 400 percussion players. Completely as a private experience. We stayed a week. It was an incredible experience.

Bernstein is quoted as saying, “A work of art does not answer questions, it provokes them; and its essential meaning is in the tension between the contradictory answers.” What is the essential meaning of Bernstein Reimagined and where do you personally find the tension he discusses?

It is one of the million answers to what he writes. One more view of the music we’re talking about. There’s no answer. This is one more possibility of his music. I think it’s great that this CD will be out and everybody will listen and have his own take and get his own ideas about it and go forward with that.

It’s another ambiguous answer for what he wrote. It’s a cycle closing again and again; whether it’s Bill Evans or the Smithsonian Jazz Masterworks Orchestra or a symphony orchestra or an opera orchestra playing. It doesn’t matter. Every single one of these is valid, is legit and has a reason to exist. That’s really what makes us use our brains and feelings. There is a connection. That’s making us having this conversation. Ultimately it is why music? What is there in music that is so fascinating? And he tried to answer that.

Main Photo: Artwork from the cover of Bernstein Reimagined (Courtesy MCG Jazz)