When Alex Ross wrote in The New Yorker about Heartbeat Opera’s 2018 production of Beethoven’s only opera, Fidelio, he said he was “blindsided by its impact.” He went on to say, “Mindful of American reality, they discarded the opera’s happy ending and imposed a bleak coda, with a scrambled, dissonant collage of Fidelio music and other Beethoven snippets to match.” Amongst the singers who appeared in that production was bass-baritone Derrell Acon.

Acon appeared as “Roc,” a prison guard in this updated version by Ethan Heard and Daniel Schlosberg. The duo have made new revisions to the original story. Stan is a Black Lives Matter activist who has been imprisoned. His wife, Leah, gets employed as a guard at the prison in hopes of freeing her political prisoner husband. Leah works with another guard, Roc.

Heartbeat Opera is starting a small tour of Fidelio which begins tonight at Met Live Arts in New York February 10th – 13th. From there they travel to The Mondavi Center at UC Davis on Feburary 19th; Scottsdale Center for the Performing Arts on February 22nd and The Broad Stage in Santa Monica February 26th – 27th.

This past weekend I spoke via Zoom with Acon about the topicality of this production, how his relationship to it has evolved since he first appeared in Fidelio four years ago and why Fidelio speaks to audiences today. This is a massively thought-provoking conversation and there’s no way to cover all the topics we discussed. To hear the full interview, please go here to our YouTube channel.

What follows has been edited for length and clarity.

Before we get to Fidelio, I want to ask you about something the head of one performing arts organization in America said when J’nai Bridges held an online discussion examining race and the issues of race in the arts from the perspective of Black artists. The response that this leader gave was “horror and sorrow that the lived experience of those artists went unheard in that wrong way.” How could this or any other executive in the performing arts not be more fundamentally aware of the systemic problems that exist in the arts?

I think it’s just that it’s systemic. There is a systematic ignorance of the experiences of those who are not able-bodied, white, older, privileged. And so it’s a shame. But we are allowed, the system allows us to continue on with our art art making without considering all of the different perspectives and experiences that exist in society. And in my part of my activism, as I imagine you know, is really trying to pull us back to what opera used to be, which was disruptive. It was meant to represent the people. People are in the 1830s and 40s screaming, “Viva Verdi” in the streets of Italy because that’s how on the pulse this art form was. Now it has become this exclusive thing or it’s trying to become. But folks like me are rebelling against that trend. I think you make a really good point in that. One can say something like that and feel like they’re being profound. But instead it really just speaks to the decades of our inability to to truly represent everyone in this art form.

Of course this isn’t just an issue for the performing arts. Just look at the lawsuit recently filed against the National Football League.

I would say opera is at the very tip in terms of just how bad it is even and in terms of the scholarship alone; of E.D.I. (Equality, Diversity and Inclusion); of what inclusion means – all of these things. It has been really surprising and scary how far we have to go. The smartest people, most inventive, innovative folks we have in our industry, don’t even understand this work. They understand how to how to provoke with a 2022 version of La Bohème but not necessarily when it comes to better representing those of us who live in society.

Let’s talk about another area that is systemically racist and that’s the prison industrial complex. Which brings us to Fidelio. Roc is an interesting character. You’re depicting a character who is sort of a cog in this prison industrial complex that is inherently racist. And I’m wondering what the challenges are for you in this production so that we understand the humanity of this man who’s trapped in a situation that maybe is his only opportunity for employment?

That’s a really lovely question because that that is the core of my journey. Being able to see Roc in the beginning of the opera with his daughter – Marcy in our version. The way he’s jokes with her and the laughing and the lightheartedness and the true love that he has for her and the love you can see building between him in our version and Leah or, you know, the original Leonore. It paints him with humanity so that by the time you get to truly understand how problematic he is in terms of all of the injustice that’s happening within this prison, you automatically have an internal conflict with how to view Roc. It’s very, very difficult to view.

How could that also be the same person who has not figured out a solution for this guy who’s been disappeared in the basement of the prison system? We have some added dialogue that helps to clarify that because I think Roc absolutely exists in society. There are many Black folks – and I’m sure folks of other races and experiences – who feel they must work within the system in order to retain whatever little power or authority they have to make changes in other areas. As long as it is intentional, then even if it’s problematic, it has some productivity. And that’s really a nuanced perspective of any marginalized group that large society can never really understand.

How has your relationship to the work evolved as situations in this country in particular have changed over those four years?

What was different about me four years ago is that my activism, my scholarship, my performance, all of these spaces, all of these hats that I wore, were sort of different buckets of my life. In 2018 a personal traumatic event happened in my life and it just began this journey of understanding that activism, justice needs to sit at the center of everything I do – no matter what.

So now coming into this work, it’s not only about how I’m interpreting the character of Roc. It’s also about how we’re rehearsing. It’s about the conversations we’re having with Ethan (Heard), the director; Daniel (Schlosberg), the music director; about the musicality of the piece or the different language that is used in the book scenes. It’s the values we’re bringing into our rehearsal process. Making sure that our rehearsal process itself is not steeped in a white supremacist structure, which a lot of rehearsal processes in classical music are. So trying to dismantle all around the production, not just within one narrow lane of character interpretation, that for me is the biggest change.

Last year I interviewed Michael Blakk Powell who was a member of the Kuji’s Men’s Chorus that appears as part of the opera. He was astounded that someone like Beethoven could relate to his experiences as a formerly incarcerated man. That the composer had the ability to so powerfully express a story like the one in Fidelio. What do you think this opera, particularly for people who don’t think opera is for them, in this production has to say that might convince them it is more than just an old work from 1884?

I think you have exactly the right point of departure and statements like Michael’s. What we have done is we’ve updated the dialogue and updated the story. So it’s so specifically relevant. It gives modern audiences, both those who are frequent opera goers an opportunity to reimagine what this score can do. But also folks who’ve never been to an opera because the book scenes alone give you the story. Then to put you into that world and to see how Beethoven’s music sort of emphasizes, takes to the next level these expressions of joy, these expressions of conflict, these expressions of agony. That is the power of music.

There is not an inherent gorgeousness to classical music itself. We find it gorgeous because we find ourselves represented in it. We have not been successful at making it relevant for everybody. It makes sense absolutely that not everyone is going to find it interesting. Let alone beautiful or insightful or our compelling or impactful. Sort of mixing up these two worlds is what I think brings relevance to everyone. Not only folks who are formerly incarcerated or Black folks, but everyone.

Beethoven said, “I wish you music to help with the burdens of life and to help you release your happiness to others.” How does your participation in Fidelio help you release your happiness to others?

I think showing the nuances of Blackness. That is my favorite thing about our production. It’s so mind-blowing that it’s within the frame of a Beethoven in opera. To bring Beethoven’s music into it with these new book scenes, I think, it’s really powerful. And it was powerful four years ago. I can tell you as someone who was a part of that production as well, this is even more powerful because with all those of us who are returning, we’ve grown up. We got it there. But now we get something else, especially after the murder of George Floyd. There’s something else that we’re inching to release to society. I think that’s what folks are going to see here.

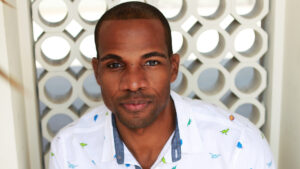

Photo: Kelly Griffin and Derrell Acon in Heartbeat Opera’s Fidelio (Photo by Russ Rowland/Courtesy Heartbeat Opera)