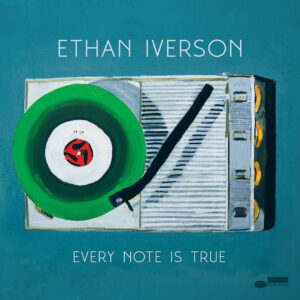

We all have unique ways – we hope – of celebrating our birthdays. For jazz musician and composer Ethan Iverson he celebrated his 49th birthday on Friday the best way possible for all of us: he released a new album entitled Every Note Is True on Blue Note Records. The album finds Iverson joined by bass player Larry Grenadier and legendary drummer Jack DeJohnette.

Iverson may be best known for the avant-garde jazz trio The Bad Plus. He recorded 14 albums with the trio before moving on. My personal favorite amongst their recordings is 2014’s The Rite of Spring. It is absolutely Stravinsky’s music, but performed in a way that is completely its own. (Which you’ll see is a theme for Iverson.)

Every Note Is True features nine original compositions by Iverson and a cover of DeJohnette’s Blue (which was the drummer’s idea during the recording sessions.)

In late January I spoke with Iverson about the album, his prolific writing and interviews that can and should be read on his blog Do the M@th and whether jazz music will ever achieve a level of greatness beyond what legendary artists such as John Coltrane and Sonny Rollins accomplished. What follows are excerpts from my conversation with Iverson that have been edited for length and clarity.

I want to start with one of your interviews with the late Terry Teachout. He concluded his comments by saying, “I think I’ll just keep on doing what I do and waiting to see what happens next. I’ve always been open to surprise.” How much does that describe your own process and how does every note as true reflect the surprise you find in your own work?

I do think it’s important to surprise yourself when you’re a composer or a piano player. Some people have careers in the arts where they really stay on a very specific track. But I’ve been lucky enough to have a more wayward experience going from thing to thing in a way. But I will say that I always feel like it make sense to me; there’s a thread there that I follow since I really started playing the piano for real. I have been aware of following a thread from the outside. It may look like it’s a mess. I don’t know, like all the different things I’ve done or who knows, but for me it’s all been logical. I guess I would also say that I hope to be keep on being surprised in the future.

How much does Every Note Is True serve as a document of your experience and emotions during these last two years and how is that reflected in the opening track, The More It Changes, which features cellphone recorded performances of the vocals by friends and family?

Everybody’s got to use what’s happening in real time. And I would say jazz improvisers are particularly suited to doing that. You’ve always got to be in the present day. When the pandemic hit, like most of my peers, the first question is when do we start working at the grocery store? It really felt like the end of everything and, of course, we’re not out of it yet. So it was hard not to see all my friends in that sort of thing. As you recall at the beginning everything was quite strict. I thought let’s just do a nod to this current moment and have a socially-distanced choir and try to bring people together through music. Even if it’s just for a short song that lasts a minute and change.

One track in particular hit me very emotionally was Had I But Known. Could tell me a little bit about that track and what it is that you wish you had known?

I really love Paul Bley and his two composers, Carla Bley and Annette Peacock. It is a little bit of my nod to that tradition. With Carla in particular as a composer, I think she’s an influence on some of the ways I think. She embraces a whole world of possibility from the very simple to the very complex. The title, there might be specific things about it that I don’t feel like sharing in an interview, but it’s not truly an original title. It’s from genre fiction.

That’s the most dissonant track on the record. But it has still a clarity, I think, a through line of pure harmony that makes it effective. It’s completely written out. I don’t improvise and I like to do something a little different, that I’m pretty sure is fairly different. Usually if it’s a trio record and the pianist takes a solo number, it’s sort of an improvised rhapsodic fantasy, you know? But this is I just read it down from my score.

On January 18th, you tweeted something that I thought was really interesting. You said “There’s nothing new, just fresh ways of combining things.” Do you genuinely believe there’s nothing new?

You could ask me about any jazz musician, for example, and I could tell you the references. But the older I get, the more I believe that is really the case, you know? All humans are essentially the same. What percentage of what’s really different between you and me? Just a small percentage. We’re all inspired by whatever we’re inspired by. You don’t wake up and have a new idea. Now there are people who are more innovative than others, but I think it’s because they’ve combined elements that had never been combined before.

I read your your essays and interviews which I think are essential reading for people just to get an understanding of the past and the present within music. What do you think the dialog you have with your audience vis-a-vis these essays and through your music will do for getting us into the future and understanding in the future where we’ve come from and what impact that will have on other musicians?

Specifically about jazz, you know, there was room for me because the critical discourse never was too informed by the way the musicians actually thought about it. And sometimes when I’m teaching a master class I talk about Beethoven. I talk about Coltrane. For me they’re equal.

But Beethoven’s been dead for so long and the best and the brightest minds have been working on his reception history for years. They’re still working on it. We’ve sort of got Beethoven sorted now. Coltrane died in 1967 and we’re still pretty new in the reception history. Within the last maybe 15 years something has gotten better as people with real talent are actually taking on the reception history of our greatest American musicians. So I see whatever I’m doing in print is part of that – just trying to sort out something because there’s nothing better than 20th century jazz that’s top table. You know, Miles Davis, Billie Holiday, Thelonious Monk, Ornette Coleman, Charlie Haden, all of that stuff that was unbelievably great. All the piano players: Art Tatum, Earl “Fatha” Hines, Teddy Wilson, Ahmad Jamal, Hank Jones. I get chills thinking about these musicians. They were so great and people sort of knew they were great. Now they’re all gone and we kind of know that was it.

That was like Beethoven and Mozart. That was an incredible moment of human creativity. So whatever I’m doing in the jazz sense there with that is just trying to get more of the musician’s perspective. When I interview Ron Carter or Keith Jarrett as a musician, maybe I get some insight from them that, you know, sometimes stuff that I think it’s pretty obvious. But then later on someone will say, I just didn’t know they thought about it that way. So that’s what I believe my role is in trying to move the ball forward and just understanding how great jazz was.

We had multiple great periods of classical music well past Beethoven. Do you think we will have multiple great periods of jazz past all those artists you just mentioned?

I don’t think it’s going to be better than John Coltrane, frankly. Sonny Rollins, you know. I made a little album for Tom Harrell. There’s nothing like that in terms of playing jazz trumpet. He’s sort an old genius of true school, shall we say. I don’t think my generation, we’re not going to quite get to what that is. So what we have to do is figure out things to add to it, to make something a little different. My belief as I turn 50 and older is formal composition will become more and more the way I try to put things together. Nothing new, exactly, but fresh ways of combining old things.

Photo: Ethan Iverson (Photo by Keith Major/Courtesy Blue Note Records)