The Los Angeles Opera has three remaining performances of Donizetti’s opera, Lucia di Lammermoor. Normally a new production is enough to make opera fans take notice. For this Simon Stone production that originated at the Metropolitan Opera the most exciting news is the arrival of Colombian conductor Lina González-Granados as Resident Conductor of LA Opera.

She has already been making a name for herself leading orchestras and operas around the world. The headline of Los Angeles Times critic Mark Swed’s review of the Los Angeles Philharmonic at the Hollywood Bowl in August said, “Conductor Lina González-Granados makes a big splash in the big outdoors in her Bowl debut.”

Lucia is an incredible opera. It has some absolutely gorgeous music and offers any soprano who sings the title role an incredible range of music and an unparalleled mad scene. But it is also a problematic opera.

The opera, set in present-day middle America in this production, is a truly tragic love story. Lucia and Edgardo are secretly in love. They keep their love a secret. Her brother, Enrico, who considers Edgardo his enemy, keeps them from getting married by lying to Lucia about Edgardo having an affair with another woman. Enrico demands she marry Arturo so that Enrico might get out of a deep financial hole. So deep is her despair that she turns to murder and ultimately devolves into madness.

Is she the master of her own fate or slave to the demands of her brother who only wants what’s best for him? This was just one of the topics I discussed with González-Granados recently. What follows are excerpts from our conversation that have been edited for length and clarity.

This is the first Lucia you’ve conducted. What discoveries did you make in studying Donizetti’s music?

I think the biggest challenge for me was to reconcile how beautiful the music is with such a grim and dark fate to this woman who was already doomed from the very first two notes of the opening. One of the most fascinating facets of discovering that is how good the orchestration is. There are instruments that speak for Lucia; all of those little micro beats into her madness. Finding those and reconciling those were the fascinating journey I had with this.

Simon Stone’s production uses video elements. Some of them are live, others were filmed in advance. Does the video element of it all require a different kind of collaboration so that the music is in sync with what the vision is?

That is actually a very interesting question because we had actually a couple of extra days of tech in order to make sense of the turnaround, the most complicated one with the camera and the turntable. I said, “Simon, if you need me to do something with my tempo or something like a pause that is necessary, just let me know.” He was like, “Absolutely not. The video, the turntables, everything should be in synch with the music and not the other way around.”

This role is so closely associated with Maria Callas, what conversations did you have with Amanda Woodbury and Liv Redpath who will both be performing the role at LA Opera?

I think has everything to do with maintaining healthy voices. That’s why, for example, I give both of them the full liberty to explore their ornaments. It’s all about what can they achieve with their beautiful voices. It’s technically so difficult that they can’t imitate anyone. They just have to own it bit by bit, note by note, in their bodies.

I attended Lucia with two women. Afterwards we discussed if in updating this opera to present day does this production overcome the misogyny that is part of this story or does it succumb to it? After all, women had far less agency when both Sir Walter Scott’s novel on which the opera was based and when Donizett’s opera had its world premiere in 1835.

That’s a very interesting point. And I don’t think there is a right answer to this. I do refuse to see Lucia as a victim of her own destiny. This modern take doesn’t re-victimize Lucia. Somehow the violence is justified the way that the end happens. The only thing that she could do was to kill Arturo. I’m not justifying that you should kill to get control of your own life. But she did take charge of it. I think it’s important to know. But I think it all depends of how you personally deal with those traumas and how you’re triggered.

I think the beauty of it is that these conversations are held and that women are thinking is this violence necessary? Do we need to reshape the conversations when we watch these kinds of operas? Lucia is not the only opera in which violence against women is the common thread. I mean Cavalleria, La Traviata, you name it, Carmen, oh my God. It comes from a cultural root of of observing these women. And I think it’s it’s worth having these conversations.

I honestly think that there is nothing more gaslighting than this opera. Even the orchestra speaks for her before she can speak, you know? And when she speaks, she sings. But at the end, everybody wants to take her voice and she just doesn’t let them. For me she’s a very strong woman.

I absolutely agree that she’s a strong woman and she’s an anti-heroine. But if her brother hadn’t put her in that position in the first place she wouldn’t be there. He put his needs above her.

Yeah. I also wonder how beautiful it would be to talk about these roles and the responsibility that is put on men’s shoulders to be a certain way. How can we reshape that? How can we have conversations about Enrico and also Edgardo treating her? How can we say that you don’t have to be responsible for your entire family’s trauma. Let’s also open the door to heal toxic masculinity. Both of them, I think, are equally important.

I want to ask you about Conductor’s Collective which you co-founded. The mission is “to create a community of potential leaders who are prepared to face the challenges of a rapidly evolving musical landscape.” What do you see as those main challenges of this landscape today?

Well, the biggest one is audiences not coming back now that we overcame the pandemic and an extremely competitive a workforce that not necessarily is relying on good artistry. How do you prepare for that? How do you keep your values as a musician intact?

And racial reckoning. Really working on the spectrum of real diversity and inclusion where everybody has a stake in the conversation for real and try to see how everyone fits into that. For conductors, it’s a tricky spot to navigate. Especially because everyone thinks it’s all about having an Instagram with good followers. You get a manager and that’s what they are telling you. Put your calendar on Instagram! Do you have a website? Everybody’s going to look for you! All of these are things are true. Do they make you a musician? Absolutely not. Are you going to be fulfilled with that? Definitely not. It’s all about introducing people to the music.

What you would like your role to be for a young Colombian girl or a young Kenyan girl or somebody else around the world who never thought what you’ve achieved already was possible?

I’m just going to plagiarize something that a one of my very early mentors has said to all of us, which is [conductor] Marin Alsop. Marin says, “I had it so hard. My only dream is that you don’t have it as hard as I did.”

I might be the first Latina in a the LA Opera, but I’m not the first woman in this season conducting or I haven’t been the first woman conducting the orchestra. I went to L.A. to the Hollywood Bowl and it was like full of women. Susanna Mälkkii was the musical guest. It’s not a situation. Nobody feels threatened. Nobody feels that their core beliefs are absolutely faced with difference and you have to feel this rejection.

It’s already a difficult job. For me, it’s already difficult. We really need to have a vision, a philosophical view of the things and on top of that we have to have good ears and rehearse well. We shouldn’t be worried about other people’s feelings about us to make our work more difficult.

The remaining performances of Lucia at LA Opera are September 28th, October 2nd and October 9th.

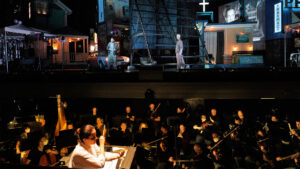

Main Photo: Conductor Lina González-Granados in a rehearsal of Lucia di Lammermoor (Photo by Cory Weaver/Courtesy LA Opera)