When his birthday rolls around in early December, Tony Award-winner John Rubinstein (Children of a Lesser God) will turn 76. That means he has early memories of President Dwight D. Eisenhower who was in the Oval Office from 1953-1961.

“I remember him. He was sort of a Éminence gris. He was in the background all the time in black and white, because that’s what televisions looked like in those days. He was sort of the uncle type – nice and accommodating. He had that sort of Midwestern accent that made him sort of accessible.”

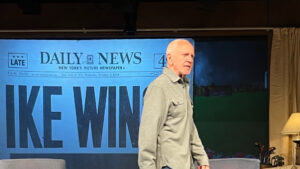

Those recollections will come in handy as Rubinstein is starring in a one-man show called Eisenhower: This Piece of Ground from New LA Repertory at Theatre West in Los Angeles. The play was written by Richard Hellesen and has its world premiere through November 20th.

Rubinstein first gained prominence making his Broadway debut as the title character in the Stephen Schwartz musical Pippin in 1972. The show was directed by Bob Fosse.

While he’s been in many a play or musical, he’s never starred in a one-man show before. When we spoke two days before Eisenhower had its first preview, Rubinstein said it was a lot of work to be the sole performer of a play.

“I’ve never been literally alone on stage all by myself with almost two hours of monologue to deliver,” he said. “To be really honest I’m an old guy. I like having a piece of work in my hands because I owe that to the audience. I owe them the best version that I can possibly deliver to them. So I feel a tremendous responsibility. The part that scares me, it’s not fun. I don’t enjoy it. And I work, work, work, work, work to make it less and less probable that there will be any of those really bad moments. I hope there won’t be one.”

Rubinstein has experienced other actors “going up” as the term is called on stage – not remembering their lines. He tells a story of an unnamed co-star in Children of a Lesser God who completely forget her lines, left the stage and when into her dressing room, leaving Rubinstein on stage alone. If necessary he’ll do what he did at that performance of the Mark Medoff play.

“The risk exists that that happens and that maybe I skip six pages and oh, yeah, here’s where I am. Blah, blah. And I start back. I’ve left out a whole bunch of stuff. Do I try to now double back and get that stuff in or do I just finish and we go home early? The audience isn’t there to see me get out of trouble. They’re there to hear a play about Dwight Eisenhower and hear this actor portray him and see what it’s about.”

Hellesen uses a true story as the foundation of the play. Arthur Schlesinger of the New York Times assembled 75 historians a year-and-a-half into Kennedy’s presidency to rank the men who had been US presidents. Eisenhower was listed as number 22 out of 35.

“He’s pissed and he had a temper. So he’s talking on the phone and then later recording his reaction to being ranked number 22. He talks about what he did, insisting he’d done great things.”

Eisenhower is best known for his battles with General Douglas MacArthur, for setting American on a path towards civil rights without truly becoming a leader and for warning about the military industrial complex. So did he truly do great things?

Rubinstein has his own thoughts, but prefaces them by saying he’s not “really qualified” to give an answer to that question.

“Yes, he did do a lot for civil rights. He did that whole confrontation with (Orval) Faubus, the governor of Arkansas. He got those Black students to get into the school and get the mob taken away. He brought in the the 101st Airborne, the same team that landed in D-Day and did the bombing and the prep for D-Day. The military industrial complex, he realized what was happening and everything that he said is now coming true. To the degree that people are conscious of it, they owe a lot of that to him. So he did a lot.”

As for his temper, even Eisenhower commented on it in a story he wrote for Reader’s Digest Magazine in 1968 called Some Thoughts on the Presidency. Of himself he said, “I found that getting things done sometimes required other weapons from the Presidential arsenal – persuasion, cajolery, even a little head-thumping here and there – to say nothing of a personal streak of obstinacy which on occasion fires my boilers.”

That self-awareness gives Rubinstein plenty of inspiration for his performance, though Eisenhower’s own upbringing helps, too.

“The first act of this play talks a lot about his father who had difficult times financially. His mother was a Jehovah’s Witness and was very, very religious, but not in a sort of crazy evangelistic way; taking the actual lessons from the Bible and using them in her life and bestowing them on her seven sons – one died. Ike learned a great deal of humanity from her and a great deal of do your duty. Everybody has to contribute. It’s all about hard work and dedication. And [he learned] everybody has to put in their two cents from his dad. Those two influences come out in the play and his life and his descriptions of what he did and how he did them. That’s deep within him and it reflected itself in his presidency.”

Presidents, leaders and monarchs have been fodder for writers for centuries. Just check out Shakespeare or what’s streaming on Netflix. Rubinstein has a theory as to why we’re so fascinated by them.

“We are like moths to a flame attracted to power. Some Freudians will always say it’s because it’s what you lack that you seek in the outside world to sort bolster you and help you feel stronger and more ready to take life on – not an easy task. When somebody shows a control over life, at least in some big or small way that you don’t feel you have, that’s attractive. You want to be like them.”

He continues to use that attraction to explain Donald Trump’s popularity.

“It can be voting for somebody like our former president, whose name I can’t say without blistering my tongue, but a guy who made this fake aura around himself of power and success on that stupid show he had where he said, ‘You’re fired!’ People thought there’s a guy who has life where he wants it. He knows what he’s doing. ‘I saw his name bigger than ten feet high in gold letters on some building I just drove by. He must really know what the hell he’s doing.’ So one’s attraction to strong individuals and rulers and leaders is understandable and often justified, but also often mistaken.”

Playwright Hellesen did an interview with Adam Symkowicz in 2013 where he talked about the tendency of American popular culture to embrace and overpraise the new as a salvation to art. He said “There are things you do not know, questions you cannot ask, abilities you haven’t yet refined, until you’ve hiked a pretty good distance up the mountain.”

Rubinstein certainly finds himself with a good view approaching the summit of that metaphorical mountain and agrees with his playwright.

“No matter how old or young you are, you are the sum total of what you’ve been through that far. That’s true when you’re two years old. The words you have, the habits you form, the things you love and the things you hate when you’re two. When you get to my age those are just multiplied by the hundreds of people you’ve known, met and lived with and experienced life with them. Through seeing children being born, watching them grow up and participating in that process, for better or for worse. All these professional engagements of different kinds.

“I guess the word that jumps to mind, and I don’t feel that I’m lying, is humility. You learn humility. You don’t necessarily become all grateful all the time. But you learn. You learn strength. You learn how to trim the fat. You get to a place where you sort of know who you are. You don’t like a lot of yourself, but you’re able to accept it and maybe counteract the parts of yourself that you know are going to get you in trouble or are going to hurt you or people around you.

“I’m lucky to be here. I’m so lucky to get to know all these people and work with them or live with them. I’m glad I’m here and and I’m going to make the best of it that I can. Not just for myself, but to try to do something good for other people, even if it’s just acting on a stage and giving them something that that lifts them, that makes them think differently than they thought as they walked into the theater. It’s not just about us. I’m humble in front of the task of living a long life.”

To see our complete interview with John Rubinstein, please go here. You can find other interviews with artists and creators in the performing arts on our YouTube channel.

Main Photo: John Rubinstein in Eisenhower: This Piece of Ground (Photo by Pierre Lumiere/Courtesy New LA Repertory)