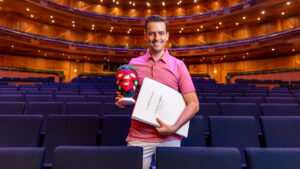

This is a story about contemporary classical music. This is also a story about Mexican wrestling. These two wildly different things come together in Lucha Libre! by composer Juan Pablo Contreras. The work has its covid-delayed world premiere on Sunday, December 11th by the Los Angeles Chamber Orchestra.

The concert celebrates, in part, the 200th Anniversary of diplomatic and cultural relations between the United States and its neighbor to the south. Contreras will be honored by the Mexican consulate for his binational artistic contributions. In October he was awarded the Vilcek Foundation Prize which is given to immigrant artists to support their continuing work.

Contreras has collaborated several times previously with LACO. Lucha Libre! is part of their Sound Investment program in which donors help commission a work and have a series of meetings with the composer to see their investment come to life.

Born in Guadalajara, Mexico in 1987, Contreras grew up with Luchadores (wrestlers) as his superheroes. When this opportunity with LACO came about it served as a perfect opportunity for him to combine two of his passions and, in the process, create a work that might bring new audiences to classical music.

In mid-November I spoke with Contreras. What follows are excerpts from our conversation that have been edited for length and clarity. To see the full, thoroughly entertaining conversation, please go to our YouTube channel.

At what point in the Sound Investment process did you come up with the idea of composing a work that celebrated Lucha Libre? And why this subject?

Ten years ago I had an opera company approach me and ask me to write an opera. My first thought was Lucha Libre is a perfect depiction of what it’s like to go to an opera – something that’s kind of rehearsed and staged, but at the same time really can bring in fans to watch these performers because they’re doing impossible things on stage. After working with LACO on a couple of smaller commissions I was offered this amazing opportunity to be the Sound Investment composer. I knew I was going to get the opportunity to really share my creative process with people and bring them into what it’s like to be a composer. I thought Lucha Libre would be really great because I’ll have the time to really share it with people and get them to know what Lucha Libre is all about.

We got really very excited about Lucha Libre. We ended up purchasing 50 masks that people are going to wear at the premiere. It became something bigger than the piece itself, which for a composer it’s really exciting because our profession tends to be very lonely.

Was Lucha Libre something that was important to you as a kid?

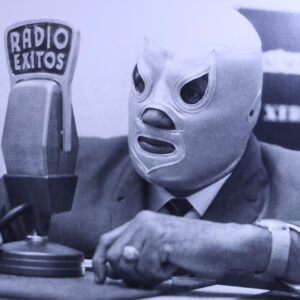

Yes, very important. These were our superheroes. You dreamed about going and watching El Santo or Blue Demon, but with the opportunity of eventually doing so in person. I even had little action figures that were Luchadores. It’s more than just the spectacle. They really reflect a lot of things also about Mexican culture which is something that interested me.

Bringing back this idea of superheroes, to me you go to a classical music concert to see something impossible happen on stage. There’s a group of musicians coming together, choreographing something that is very intricate, where everyone is playing at the top of their game and it’s exciting.

That’s the connection that I made with Lucha Libre. Everything is choreographed, everything is planned out. It’s an act that they put on for the people to enjoy. That was what inspired me to mirror that on the classical stage.

With Batman we know that it’s Bruce Wayne. We know that it’s Clark Kent behind Superman. But Lucha Libre really relies on complete anonymity. In fact El Santo passed away a week after he, for the first time, revealed who he was. How much does the idea of keeping one’s identity a secret factor into the work that you wrote?

One thing that I built into the composition was I’m going to have, just as it happens in a local arena, two teams, three rudos, which are the villains and three técnicos, which are the good guys. I geographically chose the players to be soloists within the orchestra, but they would face each other. For example, the concertmaster and the principal cello; the piano and the trumpet and the flute and the timpani. So we would have three opposing three and three on each team and facing each other.

Part of what’s fun about listening to the piece is you’ll get introduced to each of these characters by listening to their theme. When you go to a Lucha Libre match they enter the arena one by one and you hear the music that is associated with the Luchador. I wrote six different themes for each fighter. The piece starts with us listening to the themes. Then you’re going to hear two themes fighting each other: one versus one, two versus two, and eventually three versus three, where all of the themes are kind of fighting on top of each other and there’s a winner.

If you lose you need to reveal your identity. That’s the gamble that some of the fights agree on. So that would be the connection that I make. If you listen to this piece you will be able to see or hear who are the winners.

In most competitions there’s the team you root for and the team you root against. There’s the good guy. There’s the bad guy. We sometimes look at competition as an analogy for good and evil. Is there anything bigger that you want to say about the nature of good and evil vis-á-vis this composition?

The main question that I wanted people ask themselves is what is my personal identity? Who would I root for or what kind of mask would I put on more than thinking about good and evil. What kind of mask have I designed for myself? What are some of the things that I value most about my upbringing and my identity. That has been a thread that has been present in all of my music which tends to celebrate Mexican culture and Mexican roots.

If we’re going to talk about masks and identity, how does this work allow us to unmask who you are, not just as a composer, but who you are as a human being?

I think I am someone who is really making a strong effort, but in a not in a forced way, but in a really enjoyable way, to make classical music more fun and more accessible for for everyone and especially the Latino communities. I really want to bring the people who I identify most with, which are Latinos and Mexicans, to have them feel excited about going to a classical music concert. A piece about Lucha Libre, I think, is the perfect way to introduce people to certain instruments as well. That I chose six different instruments within the orchestra and having them be almost like soloists in the piece also allows people to get to know these instruments in a more intimate level. Sometimes we have this expectation that classical music is something very serious – that you can’t really laugh about it or there is no joy in that.

What it tells you about me is that I’m trying to really scream Mexico with my music and really bring it to the forefront with how I’m writing my music. At the same time just giving permission to the performers as well. I think the orchestra’s musicians really enjoy it when they can play something that is rhythmic, that is colorful. At the same time also for audience members to say this genre is very much alive and there’s music that is very exciting and relatable as well.

Three years ago you told Voyage LA that you’re “constantly competing with both composers who are dead as well as living composers.” You cited Mozart and Beethoven for obvious reasons. As someone from Mexico what influence does a composer like Silvestre Revueltas have on you? How deep is his legacy in your mind?

Very, very deep and very present and kind of challenging as well. Because of the fact that I also, maybe in a new way, but I’m attempting to combine classical music with Mexican music, more popular or folk, whatever it is. I sometimes immediately get “Oh, so you’re like Revueltas or you’re like Carlos Chavez or you’re like [José Pablo] Moncayo.” They are my inspiration, but I’m trying to do something new.

Thanks to their legacy I’m able to explore things in my music that are combining my roots with the classical medium. I remember almost exactly ten years ago I had my first big break, which was that I won the BMI/William Schuman Prize with an orchestral piece. So I was able to say here’s my validation that I can write orchestra music. Within a year I had ten performances of that piece in the States and Latin America.

A lot of people that are famous in Mexico as composers were telling me “No, you can’t be writing music that’s influenced by Mexico. That’s not the trend right now. You should be writing something that’s more European, new complexity, more notes.” And I was like, “But this is really what I want to say with my music. I don’t see why it should be prohibited.”

I’m lucky that I have stayed in my lane and get to explore ways to write music that is Mexican in nature. I think the dividends are that my music is frequently played and I’ve been really able to enjoy so many great performances. So yes, I’m part of a legacy, but I’m trying to plant a new flower in the garden now.

The Guardian in England wrote about El Santo in 2016. They said “El Santo was more than just a wrestler. He was a Mexican hero who not only elevated the reputation of Lucha Libre, but became immortalized as a Latin symbol of power and heroism.” How would you like to change the conversation about what contemporary classical music can be as both a Mexican and now an American citizen? What does success look like for you in your career to have elevated the reputation of classical music born out of Mexico?

15 years ago I moved to the US with the intention of eventually becoming a film composer because I thought that was the only way I could write for the orchestra. I met Daniel Catán, who was a fantastic Mexican opera composer. He was the first living composer that I met. I couldn’t believe you’re alive and you can write music for the concert stage and operas – new music. That changed everything to me. It put me in a path where a switch was turned on. Yes, you can be a composer. I think that kind of exposure and just showing, not only audiences, but also future generations of Mexican-American and Latino composers, there’s someone that has a similar upbringing to me that is actually a composer, that changes the ballgame completely.

If people can recognize and get used to the fact that composers exist they’re going to be more open to listen to more new music because it’s made by real people that [they’ve] had conversations with. As composers it is our job to be a little bit more social. Put ourselves out there and get to know the audience.

Sometimes classical music institutions have this idea that as long as our programing is great we’re going to fill the halls and there’s nothing else we need to do. I think that is not the way to go. I think you need to really think about the audience and bring them in and make them a part of the experience so that your organization can thrive. In bringing that audience, having them interact and get to know a composer – which is exactly what Sound Investment is about – that’s the way to change the culture. It’s like going to a temple where you have that opportunity to really interact with the music and see it come to life.

To see the full interview with Juan Pablo Contreras, please go here.

Also on the LACO program on December 11th is Dvořák’s Violin Concerto performed by one of our favorites: Gil Shaham. The concert will be conducted by Jaime Martín.

Main photo: Juan Pablo Contreras (Photo courtesy the composer and LACO)