Composer Pauline García Viardot is not well-known to modern audiences. She was a composer in the 19th century. She was befriended and celebrated by the likes of Brahms, Chopin, Charles Dickens, Franz Liszt, Clara Schumann and Wagner. She was an opera singer who so enraptured Russian novelist Ivan Turgenev after performing The Barber of Seville that he followed her to Paris and was with her for over 40 years until her death. But we don’t seem to know much of her work. Soprano Camille Zamora wants to change that.

Zamora, a soprano who has performed on opera stages around the world, was first introduced to Viardot’s work when she heard Cecilia Bartoli sing Havanaise on her 1996 album Chant d’Amour.

After getting the opportunity from Harvard in 2017 to review the manuscript of Viardot’s 1867 opera Le Dernier Sorcier (The Last Sorcerer which has a libretto by Turgenev), she set about to bring new life to this opera that had been lost for 150 years. In 2019 Bridge Records released the first-ever recording of Le Dernier Sorcier with Jamie Barton, Eric Owens, Adriana Zabala, Zamora and more.

This Friday Le Dernier Sorcier will be performed at The Wallis in Beverly Hills. Zamora, in addition to singing the role of Reine, will co-direct with Sharyn Pirtle. The cast includes Babatunde Akinboboye, Monique Coleman, Anastasia Malliaras, Karim Sulayman and Zabala.

Along with Monica Yunus, Zamora is the co-founder of Sing for Hope, an organization dedicated to creating a better world through the arts. Friday’s performance is a Sing for Hope production.

Last week I spoke via Zoom with Zamora about Viardot, the opera itself and her work as a citizen artist. What follows are excerpts from our conversation that have been edited for length and clarity. To watch the full interview, please go to our YouTube channel.

I watched your commencement speech at Juilliard from 2019. You used an expression that I had never heard, in bocca al lupo, which means “into the wolf’s mouth.” What prompted you to go into the wolf’s mouth on this project? And how did you first become aware of Pauline García Viardot?

I feel so much of my life has been determined by happy accidents. I was in the middle of a gig with a dear friend, Adriana Zabala, a beautiful mezzo soprano. We were nerding out about music, the sort of highways and byways of composers that we love. And we both said Pauline García Viardot; we have to find more of her stuff. Let’s see what else is out there.

We literally went into the Google machine and started poking around. Lo and behold it actually turned out that that very year Harvard University had collected from a private collection of this previously lost manuscript. That was Pauline’s original score of The Last Sorcerer, this amazing piece. It’s sort of an eco-feminist fairy tale in operatic form.

I don’t know that that’s the language that Pauline herself would use to describe it circa 1867. But I do believe that was her intent. It’s a piece about the often ignored voices, in particular in this case, the young, the very folk who have not really been given their due. It’s about elevating those voices that are too often left outside of conversations. And it’s about taking care of the earth and restoring the natural order.

Was there an A-ha! moment where you go, this is not just a discovery of a lost work, it’s a discovery of a lost good work?

This piece initially attracted us because we were on a kind of feminist mission to find a piece that had not gotten its due by a woman who really was reportedly one of the most incredible intellects of the latter part of the 19th century. But as soon as we started delving into these melodies they just took over.

Her music has that sense of being arresting and shakes us up. But it also just sounds so right and so organic. We fell in love with the score which we were introduced to in manuscript form. So we commissioned a transcript of it to sort of beat the official piano vocal score that we would work from.

I looked at your website for Le Dernier Sorcier and it says this opera was a hailed as a treasure by the likes of Franz List and Johannes Brahms and Clara Schumann. Was it just that it was written by a woman was the reason it was relegated to the dustbin of a private collection?

Why did it present itself in its debut in her living room with her students and herself at the piano as opposed to at the Palace gala? You know these are social questions. I think we know the answer. But I also think it’s waiting for our scholarship. It’s waiting for our study in that question. Perhaps a more recent question might be why did we wait until 2016 for the Metropolitan Opera to do its second opera [by a woman], the first having been in 1908?

Do you think she wrote with a better understanding of female voices than male composers might have?

Part of the joy of her vocalism and of all of her sort of pedagogy is that she was part of this hot moment in European vocal history. She was the daughter of one of the great voice teachers and singers, actually two of them. But her father, in particular, was a very famous voice teacher. Her brother was a famous voice teacher. Her sister was Maria Malibran who was the great diva of the age. She died in a tragic accident at the age of 28. She grew up surrounded by vocalism. This is written by someone who really understands how the voice works.

You found the work in 2017. The album came out in 2019. So there’s been six years that other performing arts institutions have now had as a result of the work that you’ve done. Have you recognized any greater appreciation of her and her work as a result of this endeavor?

I do think our ears are trained to hear opera with orchestra, which is, of course, the ideal. In Pauline’s life she worked with the resources that she had at her disposal. That was her piano with her fingers on the keyboard and her students. Her piece really wasn’t afforded that full production treatment.

Two years later, apparently, it did get a theatrical release in Weimar, I believe, and it was with full orchestra. Apparently they were under-rehearsed and it wasn’t a great orchestration. So all of that to say, I do dream of a scenario where eventually we can truly present it with full orchestra. And that will give us a bit more of the grand soundscape that you expect.

The world has undergone a lot of change since you first discovered this work and since you recorded it. Are there things that resonate more with you now about Le Dernier Sorcier than did when you first started looking at it?

I think a lot about this industry because it’s so beloved to me. I really do think that there’s something about the un-amplified voice and about this great, wonderful animal that is opera that brings together music and design and dance and composition and entertaining and the greatest melodies in the world. There’s something magical about it.

The fact of the matter is the delivery systems can be problematic. That’s the hard thing about systems. They’re hard to dismantle because they are no one’s intention. A lot of people aren’t invited in or they don’t feel themselves to be invited in. I’m particularly compelled by models that allow for the highest level of international operatic talent and all of that stuff that we call excellence, but also the most radical sense of welcome. A mutual welcome of mutual respect and of honoring the creativity that is hyper-local, even as we bring in these glorious artists from around the world.

I think all of the great companies are certainly trying to do that and I think there’s a lot of amazing innovation happening right now in our opera world. The more that we could go in that direction, the better. The opportunities in this moment are tremendous and we ignore them at our peril.

As a citizen artist and somebody who believes that education in the arts is of paramount importance, what is the prognosis for expanding arts education in a country where we’re now being told that you can’t discuss certain characteristics about people, you can’t have books on library shelves or in teacher’s rooms unless they’re vetted by a panel and who knows what their their criteria is?

It’s inconceivable to me. It really is. I think that’s actually part of the problem. I will frankly share with you that I do not know a human being who doesn’t believe that kids should have free access to libraries. So I think part of the problem is we’ve all hardened ourselves off from people who are not like-minded. That is a problem. I need to know these people. We all need to know these people across the aisle. Discourse is something that we have lost. We have two sides that are dug in.

Part of the thing about music is that it does allow us to see each others as humans before we ask what side of the debate are you on. I do think that’s tremendously important – the opportunity to come together before we get into it.

I think that most people who will come to this opera, chances are we have similar feelings about censorship. Chances are we vote in similar ways. That in itself is a problem. We need to not just preach to the converted. We need to have people who who think radically different from us. It’s really concerning that we have lost those opportunities.

Ruth Bader Ginsburg and Antonin Scalia used to go to the opera together. They would vote against each other during the week and then go see an opera at the Kennedy Center on the weekends. There is something to be said for that concept of worthy rivals being able to engage in dialogue with someone who’s not like-minded.

To watch the full interview with Camille Zamora, please go here.

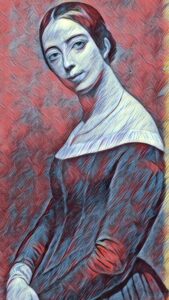

Main Photo: Camille Zamora (Photo by Liron Amsellem/Courtesy Camille Zamora)

[…] Camille Zamora Rediscovers “The Last Sorcerer” […]