In November of 1947, a new play opened at the Shubert Theatre in New Haven, CT written by Tennessee Williams. That play was A Streetcar Named Desire. On December 3rd of that year the first of what would become (so far) nine Broadway productions opened. The play has proven to be catnip for actors and directors all over the world.

The economics of producing a play has made new productions of A Streetcar Named Desire more and more out of reach for all but the biggest of actors and most important directors. The result is the limiting of opportunities to bring Blanche DuBois, Stanley Kowalski, Stella DuBois, Mitch and the rest of the characters to life for less-famous, but no less-worthy actors.

Enter actors Lucy Owen and Nick Westrate who felt passionately that the language of the play and good actors was not just right economically, but also right for the play. Their production of A Streetcar Named Desire is produced in unique locations without using a set and without using props. Owen portrays Blanche and Westrate directs. They are both co-creators.

Their Streetcar Project has been staged in a variety of venues. Tonight they conclude the last of three nights in an old airplane hangar in the Frogtown area of Los Angeles. On Friday they will open in a 3-night run at an artists workshop in Venice. Additional performances will be announced for the East Coast soon.

Last Friday I spoke with them about their production, how it celebrates Williams’ language and how audiences find themselves listening and using their imagination to enter the world of three very haunted people. What follows are excerpts from our conversation that have been edited for length and clarity. To see the full interview, please go to our YouTube channel.

Q: Artistically, what made A Streetcar Named Desire the play for which this kind of setup would work?

Owen: It just came out of a desire to work on this play and work on the character I’m playing, which is Blanche. Streetcar has been a favorite play of mine for a long time, like it is for a lot of people. And Blanche has been a favorite character of mine for a long time. Nick and I frequently refer to her as the female Hamlet. I just had a desire to work on her. And it came out of the pandemic, a dry time for a lot of creatives. We developed this slowly together out of necessity and out of what was available to us.

Westrate: The main thing we had available were these actors, their voices and their bodies. What we ended up finding out was that it’s a great language play. The characters say a lot. They tell you what they’re feeling. They tell you what they want, what they need, what they desire. And we started treating it like Shakespeare. You see Shakespeare performed a lot on a bare stage with nothing. So we started wondering what if you did that with Williams?

Q: How much of what you two are doing is motivated by the commercial demands of what theater is or how it is defined presently, not just in New York, but around the country?

Owen: Theater is changing so much. The demand for it is changing so much and getting and it’s quite expensive to make. Many theater companies rely on a star model. You have to have a famous person in one of these roles in order to make it viable financially, which is really understandable. But what it means is that working-class actors, of which I am proudly a member of that class, don’t get an opportunity to engage with this poetry. That’s just such a shame to me because there’s so many good actors who I want to see play the big, good, gorgeous roles. I don’t only want to see the same ten or so incredibly famous actors play all the same roles.

Q: We’re having this conversation a day after it was announced that Back to the Future – The Musical is closing [on Broadway] in January. It was capitalized for over $20 million and is not recouping a cent. I understand the idea behind established products like a Back to the Future. But imagine if Tennessee Williams was living in a world where only already established IP was what was performed. How would a Tennessee Williams today ever find his voice or his feet in theater?

Westrate: It’s an amazing question. I don’t think he would. I think we’re in an era [where] there’s a lot of fear right now. And so people are reaching toward something that they think is a sure thing.

Owen: It’s so disappointing for all artists personally. Every actor I know has gone through periods. Really established actors are losing their health insurance, writers are losing their mortgages, and artists are really, really struggling. Working class artists are really struggling.

Westrate: We talk a lot about path dependency in the arts, and you never change the path unless you actually try something new.

Q: Elevator Repair Service started doing staged readings of novels like The Great Gatsby. That seems like a great idea given how much people are listening to books on tape, but it isn’t necessarily what one would think of as theater. But it feels like there is at least a desire on artists’ part, if not also on theatergoers, to not be hit with the bombast that is usually associated with big commercial theater.

Westrate: We live in such a visual age. We’re constantly looking at screens that are showing, showing, showing. This production asks the audience to really listen and it turns on the imagination in a way that I think people have forgotten.

Owen: It’s been galvanizing to interact with our audiences as we do this, because it’s been a risk for us. I’ve never done theater quite in this way before. Our audiences get to engage with their own relationship with the play and their own relationship with the characters, partially because they’re listening and their imaginations are turned on. But also, and I’ve heard this from a few people, it is partially because there isn’t the most famous woman in the world, the most famous man in the world, playing Blanche and Stanley. So they get to focus on hearing the play instead of focusing on celebrity or something spectacular visually.

Q: It’s not like when A Streetcar Named Desire was first on Broadway it had the best known actor in the world as Stanley Kowalski. [Star Marlon Brando rocketed to fame after appearing in the play in New York in 1947.]

Westrate: He wasn’t at the time. For so many years I thought that this play was about a sexy guy. It’s really not what the play is about. It’s a play about two women. I’ve never seen a production, until this one, that we have a play about two sisters. That’s ultimately what it’s about, in my opinion.

Owen: I’ve seen some gorgeous productions. I’ve seen beautiful performances. But I don’t know if I’ve ever seen a Streetcar that was an ensemble. Ours is an ensemble. It’s about four people. It’s about their relationships. It’s about the devastation that they experience together.

Q: Given that you’ve had multiple audiences see and experience this way of telling A Streetcar Named Desire, how do you think the play is resonating that is unique to your production?

Westrate: Great writers like Williams and Chekhov were writing for the future. [They] were interested in the future. Tennessee Williams has a beautiful quote in the preface of Cat on a Hot Tin Roof that “personal lyricism is the call from prisoner to prisoner, from the cells in which each of us are sentenced for our lives”. That’s a call that he’s making across the decades, across the generations. When you come to see the show, you’ll experience we’re really all just people in a room and a few people are going to speak. That’s the event. That’s what happens.

Q: Aren’t you basically sort of forcing the audience to see, not just in themselves, but in the other people in the theater, some parallels to what’s going on amongst these characters in the play?

Westrate: I hope so. I think it lets the play live right now. There’s this great dialectic between Stanley and Blanche in this play about realism versus magic, about the life of the mind versus hard facts about the value of imagination, about the value of art versus the wisdom of the body. Like there is this real conversation happening between these two people who have diametrically opposed worldviews that I think is very relevant today.

Q: You said the great playwrights like Tennessee Williams wrote for the future, not for the past. If we were to use A Streetcar Named Desire as an example of writing for the future, what do you think A Streetcar Named Desire has to say about our present, and by extension, our future?

Owen: A line is ringing around my head right now, “Don’t hang back with the brutes.” It’s a famous line of Blanche’s to Stella about investing in your better nature.

Westrate: The line that immediately rings in my head, though I’ll say this wrong, is “deliberate cruelty as the unforgivable sin.” “The kindness of strangers” is the line everyone remembers. But there is a call for kindness and understanding. There’s a call for listening. I think the production calls for people to listen. And the tragedy of this play is watching these characters not be able to hear each other and the situation they get in because of it. So I guess Tennessee is asking us to listen to that call from other people, no matter how strange or bizarre or troubled they might be. We’re hoping to unleash some ghosts into America that will call all of our better natures forward.

To see the full interview with Lucy Owen and Nick Westrate, please go here.

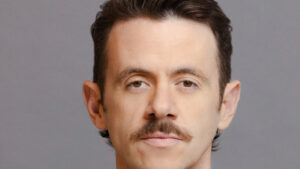

Main Photo: Lucy Owen in “A Streetcar Named Desire” (Photo by Walls Trimble/Courtesy The Streetcar Project)