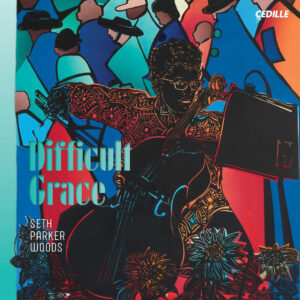

It goes without saying that we live in complicated times. At first impulse we probably want to ask ourselves why? Taking a different approach might be to look at the past as a way of understanding who we are today. Cellist Seth Parker Woods takes that concept one step further by exploring the past – and by extension his own identity – through the lens of predominantly modern classical composers on his album Difficult Grace, which is being released on April 15th by Cedille Records.

The album is a recording of much of the material that appeared in his stage show, also called Difficult Grace, which had its world premiere at the 92nd Street Y in New York in November of last year. In this project Woods performs works by Monty Adkins, Frederick Gifford, Ted Hearne, Nathalie Joachim, Coleridge-Taylor Perkinson and Alvin Singleton.

On Difficult Grace Woods serves as narrator through stories about the Great Migration, selections from The Chicago Defender (an African-American newspaper launched in 1905) and poetry by Kemi Alabi and Dudley Randall.

It’s a massively ambitious and impressive project. In early March I spoke with Woods about the project, distilling a multi-media stage project into a recording and how he hopes to get audiences to embrace what he calls “modern classical music.” What follows are excerpts from our conversation that have been edited for length and clarity. To see the full interview, please go to our YouTube channel.

In a story from late 2021 that was published at University of Buffalo you said, “I haven’t taken an easy route, but it has allowed me to tap into a wide variety of fields and areas that most people never get to because they stay siloed.” Is that diversity of fields you speak about crucial to how we look at music today, where traditional labels and definitions need to perhaps be relics of the past?

I think so. I don’t think there’s been as many artists that have truly lived or existed or created inside of a singular label. A&R people, how do they sell us as artists to the general public? And how does one talk about the art and the music we make? I don’t think it can be boiled down to just a singular label, a singular silo. Maybe it’s just easier to put it within that.

I try to think of it sometimes [as] modern classical music as we are living in the modern times. Not necessarily contemporary music, but just the modern times of creating this. I feel like they are possibly just relics of the past. But we, as I have said before, love to hold on and revel in that which has long gone and sometimes not necessarily support enough of what’s happening right now.

Difficult Grace is certainly a project that’s going to challenge us to move forward. It started as a multimedia project that you perform on stage with dancers and projections. What modifications did you have to make for this to become a recording that lived and breathed just by virtue of its sound?

There are so many visual components to the work. That was the hard part. For those that have never seen the live show Difficult Grace, how do I still convey that sense of vividness and adornments in a sonic format? How do we reposition it and allow it to kind of really soar and ride many waves in different formations was the trickiest part of putting it all together beyond how I sculpted it in the live show. Trying to use the live experience as a way of sharing it similarly to how I feel it when I’m doing it live.

Having the liner notes also helps since we don’t get to see the words that were projected on you. The ability to see what’s being said certainly helps us fill in a few of the blanks as well.

This day and age so many people gravitate directly towards digital streaming downloads. I still love a CD. I still love an LP – the actual physical thing. So for those that do buy the physical album, you get to see a lot of the visuals of Barbara Earl Thomas, of Jacob Lawrence; the words and text of Dudley Randall and Kemi Alabi and the texts from The Chicago Defender as well. It’s all very much so woven inside of the actual album and the booklet that comes with it.

You were talking about this project with the Gothamist last year and you said that Difficult Grace examines, “stories that [the body] holds and it needs to tell.” As you prepare for the release of this album and you have future performances of this work, how has your need to tell these stories shifted? Do the different ways of telling this story in live performance versus recording allow for any form of catharsis or better understanding of why your body holds these stories?

I guess in that way we are born – as we’re born – maybe questions come up along the way as we make our journeys. Maybe more questions that we still need to ask, but we don’t necessarily ask. So this is a way, through these people, through their narratives, especially with like the work, the race 1915 to embody these real live lines from journalism that were coming exclusively from The Chicago Defender.

These stories, these journeys, are so deeply connected to my family and my grandmother. My mother’s mother was making the journey just two decades after 1915. So it’s not autobiographical, but it’s kind of semi-autobiographical by lineage and connection to my grandmother in that way. So it felt so close to home to be feeling as if there was a deep importance for me to talk about it at this point.

It was a lot to to swallow. I remember the first live performance I did of it was February 9th, 2020, just before everything shut down. I was nervous because I made it a point that when I take on such performative works in this way I’m not just the cellist. I have to figure out what the characters are. What more are they trying to say beyond what’s just kind of topical. Same with music; reading between the lines.

There was so much heartache, but also there is so much perseverance. It’s not as if I was reading fiction. These are historical lines, historical documents, objects that are recounting times that were happening across the country in the beginning of the Great Migration.

You’ve described yourself as a vessel for these people’s stories in Difficult Grace. How does being that vessel impact you physically and emotionally?

I was shouldering a lot because I think this project is so personal and so special for me. When one is commissioning or one finds new work, old work, whatever it is, you don’t really know what it is until after you perform it. You may not know what it is for a few performances. There is a risk in even choosing. There’s even more risk in daring to perform. Do these works work together? What is their throughline? Even after the first performance I didn’t know. But I remember there being a sense of electricity that was going through me, but also because I was just trying to get this thing right.

Now I’m not so scared of the material. These works have changed me. I think it’s allowed me to show more of my humanity, even more of it, and more vulnerability on stage and to be okay with that and not feel overly perfect or have to search to find the perfect performance or deliver the perfect performance.

Composer John Adams and I discussed how much of the work that’s being created now is going to be remembered in the future. He said it was important to remember that Beethoven had a lot of contemporaries, but we don’t really hear a lot of the works they did because they just didn’t hold up. When you’re collaborating with as many composers as you are, do you ever have a sense of how history might look at these pieces or any belief that they are going to have a life span beyond this moment in time?

It’s hard to know. I don’t think there is a direct answer for that. Did Beethoven know symphony number five would be the biggest hit and would be played centuries later? No, he didn’t. You take a risk, but you’re also writing so much.

I don’t know if I have a direct answer as to whether the work I have been involved in creating or championing will stand the test of time. And I don’t know if I’m necessarily interested in that. What I am interested in is really trying to tell their stories now and doing the best I can to give them as many legs as possible. That it is beyond one performance. If I can get ten performances over a few years that says a lot.

I think it’s at least important for me to be able to continue to broaden and widen your palette so you don’t stay closed off to the idea [of] this is what I really like and this is all there is out there and that’s all I’m going to ever pay attention to. There’s so much that’s being made daily and weekly. It’s just finding the sonorities, the storytelling, that really resonates with you. Which, I guess in some ways, is why I wasn’t one of those musicians that was trying to prove myself or push myself to learn every single piece in the canon.

When you’re talking about the canon you’re typically talking about the 5 to 10 pieces that everybody knows.

Exactly. But that, even of itself, is a gate-kept situation. I’ve prided myself and pushed myself to pull from the composers that I really love and the pieces that I really love from those composers and pair them alongside new works being created now. Or at least in the last 50-60 years that I find to be really powerful that can have conversations across timelines.

A composer like Ted Hearne, whose work I admire greatly, there are people who are going to say that work is too difficult for them. What are the challenges for you in hopefully winning over those skeptics who think that this is just an intellectual exercise and not an emotional one?

I think it’s important to talk to your audiences first and foremost. There was a time where I was coming up and I wasn’t taught how to engage audiences. The idea of engaging audiences was just playing to them – at them. I want to actually talk to them and guide them through what they’re going to experience and hear.

I think that’s always an issue when concertgoers are thinking about or going to concerts of contemporary music. They are not in the know; something’s being kept from them, hidden from them. They don’t know the formula or it’s not the formula that they’re used to experiencing.

I don’t really like program notes in that way. I would rather just talk from my heart about what this work is, what it means to me, connections to the composer – whether alive or dead – and where this work is now and and also how it links curatorially to the rest of the program.

Artist Jacob Lawrence, whose 60-panel The Migration Series helped inspired Difficult Grace, said about his creativity, “If at times my productions do not express the conventionally beautiful, there is always an effort to express the universal beauty of man’s continuous struggle to lift his social position and to add dimension to his spiritual being.” How important is it for your work to do the same thing, and to what extent do you believe, or at least hope you’ve been successful in that effort?

Jacob Lawrence coming in heavy. Long ago my mother said to write your life in pencil. And I stand by those words. Those have been words that have guided me for all these decades because I truly believe in the idea of trying to be as open as possible. Have your your goal, your bucket list, your plan, but also be open to other things. Aligning with that or converging with that can expand or re-route what you thought you would ultimately only be doing, but may be this plus.

When people ask me would you describe yourself as a cellist I always say, cellist plus. Because I’ve taken on so many other things and things that I realized that I really do love or that I am really good at. For me it has been a grappling of how far do I want to take this career? How far do I really want to take myself? The cello, in and of itself as an expressive vehicle, has taken me around the world.

I have been in conflict with the idea of should I have just taken the easier route and just solely dedicated my life to just playing just classical music? Or at one point just doing only early music. Or have I done the right thing in choosing to do the old and also to do the new and find ways for them to talk to each other. Therefore, lifting myself further up and kind of immortalizing even more of my humanity and being able to be that vulnerable in front of so many others; if and only when it holds and leaves space for others to be vulnerable too.

It’s a gift to be an artist because we are of the few that really are mirrored reflections of society. We are the ones that set the trends. We are the ones that tell the stories that are hard to be told or that are hidden in many ways. It’s a privilege for me to have arrived where I am now. To be able to actively choose the stories, regardless of timeline that I want to, and to champion them in the best possible ways that I can. The ways in which I see those stories and the ways in which I see myself connected to them will evolve. I can keep practicing and continue to get better at telling those stories.

To watch our full interview with Seth Parker Woods, please go here.