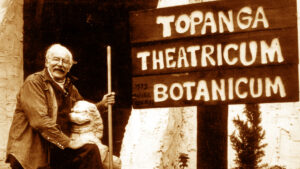

It began simply enough half a century ago. But the circumstances that inspired the creation of Theatricum Botanicum in Topanga, California were hardly simple. Will Geer, best known as Grandpa Walton on The Waltons, had been blacklisted during the House Un-American Activities pursuit of communists. Without any secure means of working and earning an income, Geer created an outdoor theater where other blacklisted artists and singers could come together to perform.

He probably couldn’t foresee that his theater would still be thriving fifty years later. Nor could he have known that his daughter, Ellen Geer, would be the Producing Artistic Director when that golden anniversary came around. She has programmed an ambitious season that opened two weeks ago with a production of Shakespeare’s Macbeth, which Geer has directed. One night later their ever-popular production of A Midsummer Night’s Dream opened.

This week a passion project of Geer’s opens, Queen Margaret’s Version of Shakespeare’s War of the Roses, which she compiled and directed. It takes Queen Margaret, the women and children from Henry VI Part I, II, III, and Richard III and puts them at the front of the story. The last production to open during this season is Terrence McNally‘s A Perfect Ganesh which opens July 15th.

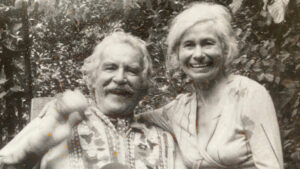

Recently I spoke with Geer about the 50th anniversary, her father and mother’s legacy (her mother was Herta Ware – perhaps best known for her role in Cocoon), and what the future might hold for the truly independent theater that has beaten the odds and then some. What follows are excerpts from our conversation that have been edited for length and clarity. To see the full interview, please go to our YouTube channel.

I don’t know if you’re a particularly spiritual person, but I do know that both your parents’ ashes are scattered on the grounds at Theatricum Botanicum. Do you feel their presence with you as you launch season after season and, in particular, as you launch this golden anniversary?

You know, they’re in your cells. Young people like to deny that. Maybe they get along with them well. But my parents are very deep, deep in my cells. And actually, Pappy would said, “I’m going to be good compost.”

A publicist once told me that when an actor does an interview for a project, it’s not about that job. It’s about getting the next job. What does this season tell us, not just about where Theatricum Botanicum is today, but also what its future might hold?

We just had a board meeting last night. That’s a big thing that we’re all talking about because it’s evolving. My daughter Willow has stepped forward like I can’t believe. She’s my Associate Producing Artistic Director and my nephews, who have been in Europe for years as musicians, now want to be more involved. Always in an in an organization like this it’s how you can make a living and yet do this hard thing. Because it is a hard thing to do theater like this where people don’t make a lot of money – unless you’re doing the big musicals and Broadway and all that. You have to have a deep passion to do to do this. So I see the future very, very clearly. My family still seems to be the core and we’re fourth generation on those boards. My granddaughter’s going to do the young Queen Elizabeth today in our history compilation. So that’s good.

I read a lovely interview you did with Steven Leigh Morris for American Theater magazine in 2016. You said, “You don’t teach by preaching. You teach by the way you live your life.” What stands out to you most about what you’ve learned from the way the people around you live their lives in the theater?

It’s a team. It’s working together and it’s alright if it’s not the greatest thing since sliced bread. Sometimes when I’m thinking about a season, I’ll look at our actors and say, Oh God, that guy or that gal is ready for this. We always have casting calls, but when you have a company you begin to invest your care about them and it becomes part of your life. They become part of your life and you care about their next steps. You know, are they dating? I mean, all that’s a part of it. What happened to them during COVID? Oh, there’s something that’s going on with that person. How can we help? That’s all a part of living, isn’t it?

Also, whatever happens in any given day is going to be that intangible thing that finds its way somehow into a performance. You don’t know how it’s going to manifest itself, but it does find its way into a performance, doesn’t it?

It does. Especially with young people. They haven’t lived in and had some of the hard knocks and the good knocks, been through a bunch of relationships that are great or they fail or jobs that are great or they fail. They haven’t been there yet. As you get older, I don’t know if it is with you, there’s a marvelous thing of sitting back and saying, oh, my God, that’s what’s happening to them. How can I help, you know?

A Midsummer Night’s Dream is the signature production at Theatricum Botanicum. What are the challenges of making the play not just fresh for your audiences, but also fresh for the company?

That is the play, if I pull it out of the season, everybody gets upset in the audience. That is the play where you bring in young performers out of college or out of high school because there are young, wonderful, vibrant parts and it’s magical. It’s the perfect learning place for an audience who’s never seen Shakespeare. For young people who are striving to encompass it within their acting realm, it’s just perfect.

Then, of course, you’ve always got young people as the fairies, so you can get your fairies from the community. And then the parents come. Those are the gifts that you get when you hang in there for a long time working on something.

There are a couple of lines in A Perfect Ganesh that I really love. One of the women prays to open her heart to India and she says, “Let me experience fully these people who are so different from me. Let me be part of this fabric, not to disappear into it, not to become them, but be with them.” How does Theatricum Botanicum allow you to let your heart expand?

Because you’re telling these incredible stories. When you’re an actor you suck in the character and whether they’re bad or whether they’re good or whether they’re ridiculous or it’s a comedy farce, doesn’t matter what they are. You have to become them in order to portray them and share them with this audience. That’s our job.

There’s a lot of conversation about having lived-in experiences to be able to play a character. I feel like that flies in the face of what good acting is. It doesn’t mean that you can relate fully to that person, but you can, at least for that period of time, enter that person’s shoes. Isn’t that what acting is?

Oh, yeah. And it’s the imagination. If you’re playing a part where a woman has a baby and this person never had a baby, you do your research. You talk to people. That’s what acting is. The research part of it in the beginning is so exciting for actors.

There’s also conversation about what’s appropriate, what isn’t appropriate, what’s acceptable. There’s more and more censorship creeping its way into our civilization today. In your view, is theater in and of itself a political act?

Isn’t life political? The only time I get upset is when the government starts using the word theater. They’re talking about war and everything else. We’re part of the politics of the world. In theater you’re telling the stories of what can happen, what might happen, what is happening here. And then, of course, you’ve got your other kind of theater, which is [she sings a vaudeville riff]. So it’s everybody feels good and it’s all okay. You can go home and have your ice cream and and that’s needed, too by human beings, you know. So these are the choices you make.

What was the inspiration for Queen Margaret? Because I feel like if we’re looking at a woman’s view of the War of the Roses, I can’t help but think that there is some kind of commentary on the role of women in history and the role of women today.

And the role of women in theater. These histories aren’t done and there’s some brilliant writing in them. Queen Margaret happens to be a person who goes through Henry VI Part One, Two, Three and Richard the Third. Then she says, Oh, you guys are stupid and I’m leaving. I’m going back to France. I always find that fascinating. She was a warrior. She was a mother. She was a lover. She was all these things.

Looking at those histories, I got excited about all the women because if somebody does one of these plays they very often cut the women’s parts. I start with Margaret voiceover and then Joan la Pucelle [Joan of Arc]. She was the first one. You’ve got the Duchess, you’ve got Queen Elizabeth, you’ve got Eleanor – wonderful women. And for the most part we do their scenes fully. It’s turned out to be almost a look at what happens when you have the elite of the world governing and deciding how they’re going to run a country. “The commoners. Go away. You’re bothering me. I want this. I want to get this.” It’s very like our government today.

Or like the way celebrities function in social media.

Or the top dogs. We’ve always had trouble with the upper class, lower class or lower lower class it. I haven’t got tons and tons of time left on this world. So all I can think of doing now is can we just blend? Can we see how wonderful every everybody is? All the different cultures and religions and be proud of them and blend? This power thing is very upsetting.

That’s one of the reasons I did this play and why that’s political to me is because when can people realize that we are continuing the same thing over and over and over again? When are we going to get to the point where we’re going to say, cut it out? Are we going to get to that point where we stop this? It’s tomfoolery, isn’t it?

I want to ask you something about your father. He was in the first season of the famous Phoenix Theater in New York. In 1954 he was in a production of Chekhov’s The Seagull. You’ve got Montgomery Clift and Maureen Stapleton and countless other people. I realized there’s so much people don’t know about Will Geer beyond his television and film roles, beyond this theater that he co-founded. What is the one thing you wish people knew or understood more about who Will Geer was as a man and an artist?

It’s what he gave to his family and the people around him: an endless exuberance, optimism about life. Especially watching him when he was crushed by HUAC. How he related to it. He related to it in a way of deep understanding of those people who were rats. That was quite something then because everybody took sides. We were totally wiped out as a family. I learned how to steal food because we didn’t have any. Papa grew most of the food that we ate. We had to kill chickens that we loved to eat.

To see how he went through that and still could encompass why human beings had to take that side. He understood the horrible politics of it, and he forgave where many people didn’t. Many people committed suicide. Many people had anger for the rest of their life. It affected them. It affected their family. It affected their work. But Pop, he was an optimist till the day he died.

Since I brought up The Seagull, I thought it would be only appropriate to end with asking you about something that Anton Chekhov is quoted as having said. “You should feel a flow of joy because you are alive. Your body will feel full of life. That is what you must give from the stage, your life no less. That is art to give all you have.” What have you gotten most from Theatricum Botanicum and what would you like the future to hold for the theater when you’re no longer able to be a part of it?

We meet the best people in the world in theater. I’ve been in the secretarial world. I’ve had to sling hash. But there’s something about this here. You can create a community and that community gives to the bigger community. You can say this is a great part. You go for that part. You’re much brighter for that. For me, it creates an enlargement. We’re just little specks on this earth and the little time that we have we got to give to each other and serve. The rest is around us: the viciousness, greed, the power, bossing young people around and not letting them find themselves. So I hope that it goes on and that the community will still love it and it will go on passing on what these wonderful artists know to other people. That’s that’s what I hope.

To see the full interview with Ellen Geer, please go here.

Main Photo: Ellen Geer at Theatricum Botanicum (Photo by Lisa Adams/Courtesy Theatricum Botanicum)